Microsurgical Practice and Surgeon Burnout: A Survey from Data of International Microsurgery Club on Facebook

October 31, 2020

https://doi.org/10.23999/j.dtomp.2020.10.1

J Diagn Treat Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2020;4:181–90.

Under a Creative Commons license

HOW TO CITE THIS ARTICLE

Ganry L, Guinier C, Sanjuan A, Hersant B, Meningaud JP. Microsurgical practice and surgeon burnout: a survey from data of international microsurgery club on Facebook. J Diagn Treat Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2020;4(10):181–90.

Contents: Abstract | Background | Methods | Results | Discussion | Conclusions | Conflict of interest | Disclosures | References (31)

ABSTRACT

Background: Microvascular surgeons (synonym: microsurgeons) are generally satisfied with their career, but are more prone to burnout than the general population. Demanding training and post-operative microsurgical complications seem to be one of the risk factors. The authors evaluated the relationship between intensive microsurgery practice and physician burnout in the setting of the International Microsurgery Club (IMC) Facebook Group.

Methods: Using the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) Score, an online survey was performed focusing on demographics, habits, as well as working environment. Comparisons were done between reconstructive surgeons with or without intensive practice.

Results: One hundred and eighty-four surgeons were enrolled. In aggregate, 37.7 percent had at least one symptom of burnout based on MBI score. Univariate analysis of burnout status found only one statistically significant result correlated to age (p = 0.048). Burnout status was not correlated to the number of microvascular anastomoses performed (p = 0.466). A two-way ANOVA analysis found an association between age, relationship status, gender and illicit drugs use independently associated with “Number of Microanastomoses,” but never with “Burnout Status” (all p < 0.05).

Conclusions: Burnout status of IMC’s surgeons was not correlated to any intensive microsurgery practice. Being part of an international group could be a protective factor, especially for young or isolated surgeons worldwide.

BACKGROUND

Physicians are generally satisfied with their career but are more prone to burnout and dissatisfaction with their work-life balance than the general population. This becomes a burden and alters their quality of life.1 Burnout is a psychological syndrome characterized by increased emotional exhaustion, a feeling of detachment, a sense of ineffectiveness and lack of personal accomplishment,2 and is caused by work related stress. In the medical field, it is associated with increased medical errors, patient dissatisfaction, absenteeism, substance abuse, suicidal thoughts or even suicide.3–5 Previous studies have demonstrated that amongst physicians, burnout rates are especially high in surgical specialties compared to other medical specialties.5,6

On the other hand, it is commonly believed that performing microvascular free flap surgery, related to performing microvascular anastomosis, may lead to a difficult balance between intensive professional stress and personal life. Reconstructive surgery demanding microvascular surgical skills requires indeed special surgical techniques with finer instruments and a microscope. Common postoperative complications such as surgical revision at any moment (day or night) or flap failures remain unfortunately steady around 1 to 5 percent of all cases, even for the most experienced microsurgeons.7 This leads to the well-known stressful reputation of microvascular surgery.

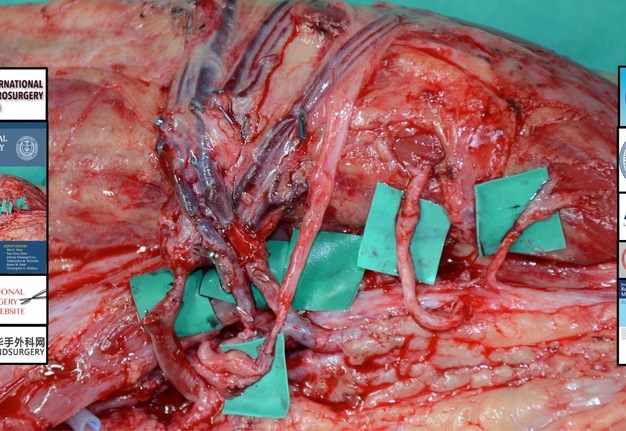

Nowadays, an increasing number of online platforms such as independent websites, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and LinkedIn have become popular for continuous medical education,8 especially in a high expertise field such as microsurgery during pandemic times. Information exchange such as surgical technic is being revolutionized by internet in an easier and faster way. An example of successful social media used for microvascular professional learning is the “International Microsurgery Club” (IMC) Facebook group, starting in Taiwan, May 2016 (Fig 1). It quickly has expanded to gather at the time of this study around 11,500 surgeons from around the world.9,10 Given no previous studies were conducted on the topic on the association between intensive microvascular surgery (synonym: microsurgery) practice and surgeon’s burnout using online platforms, this study aimed to investigate this issue using IMC social media platform.

FIGURE 1. Logo of the International Microsurgery Club (IMC) Facebook Group. This logo own by IMC includes: Intraoperative image depicting a free neuro-muscular transfer with multiple microvascular and neural anastomosis (gracilis), also used for the front covers of the International Microsurgery Journal (IMJ). It is associated with multiple other logos supporting IMC: The Journal of Reconstructive Microsurgery (JRMS), Handsurgery, Asociación Latinoamericana de Microcirugia (ALAM), International Course on SuperMicrosurgery (ICSM), World Society for Reconstructive Microsurgery (WSRM) and Asian Pacific Federation of Societies for Reconstructive Microsurgery (APFSRM). Courtesy of Dr. Tommy Nai-Jen Chang (Taipei, Taiwan) and the IMC Facebook Group Link which counts 14.5K participants (as of October 27, 2020).

The purpose of this prospective multicentric online survey study is to identify whether members of the IMC Facebook group have a higher burnout status in the group with intensive microvascular practice (defined by a number of anastomosis per month of 2 and more), compared to the group with less intensive practice.

METHODS

STUDY VARIABLES

The primary outcome variables of the study were the number of anastomoses performed by surgeons and the evaluation of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) Score. Number of anastomosis was recorded as less than two, or two and more performed per month, defining our 2 groups. The MBI score analysis was identified via three dimensions of burnout split in three categories each (low, medium and high)11: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment. Average working hours was evaluated in five categories of 10 hours scoring below 40 hours per week to over 80 hours per week.

Covariates included demographics, sports practice, smoking, illegal drug and alcohol use status as night shift rotation. Demographics included sex, age, marital status, number of children, country, surgical specialty and surgeon’s type of practice (private practice, academic, mixed).12

BURNOUT EVALUATION

Burnout among physicians was measured using the MBI, a validated 22-item questionnaire considering as the criterion standard tool for measuring burnout.13–15 Consistent with convention,16–18 we considered physicians with a high score on the depersonalization and/or emotional exhaustion subscales of the MBI as having at least one manifestation of professional burnout.13 MBI was designed to detect physicians with burnout syndrome (corresponding to high score on the depersonalization and/or emotional exhaustion combined with low score on personal accomplishment). Reverse score shows a physical, emotional and intellectual wellness and satisfaction with work-life balance.13

DATA COLLECTION AND MANAGEMENT

Three months electronic anonymized survey records meeting the study criteria were retrospectively reviewed through Monkey Survey website Link for collection of study variables. Invitation to participate to our 5 minutes online survey was sent through the IMC Facebook Group each month during 3 months between February and April 2019. The collected data was stored in our University Hospital – sponsored Research Electronic Database designed specifically for the research project. Half of the data on demographics, smoking, illegal drug and alcohol use was recorded as binary data (present or not present).

DATA ANAYLYSIS

Descriptive summaries were recorded as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and medians and quartiles for numeric variables. Comparisons among groups of microsurgeons and non-microsurgeons were done using the Pearson’s Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test as appropriate, as there was only categorical data and not continuous ones. A two-way ANOVA analysis was performed to identify factors associated with the “Number of Microanastomoses” and/or “Burnout Status”. A post-hoc test (synonym: Tukey`s test) or odds ratio (OR) was used as appropriated to determine in the two-way ANOVA analysis which group for each significant independent variables significantly differ from each other. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were done using IBM SPSS Statistics® for Windows, Version 25.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, United States).

RESULTS

Out of the 11,476 physicians of the IMC Facebook Group who received an invitation to participate at the time of our study, 184 (1.6 percent) fully completed the survey.

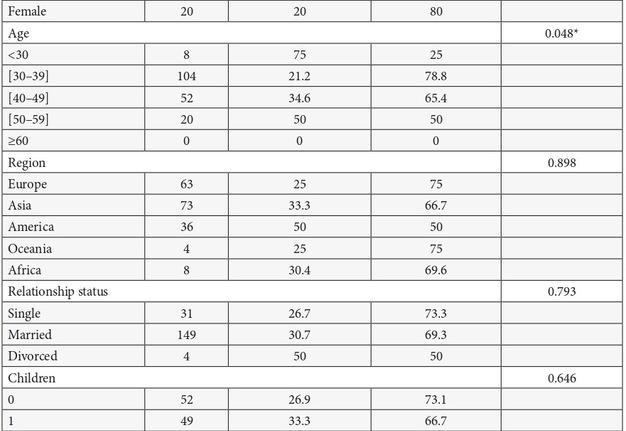

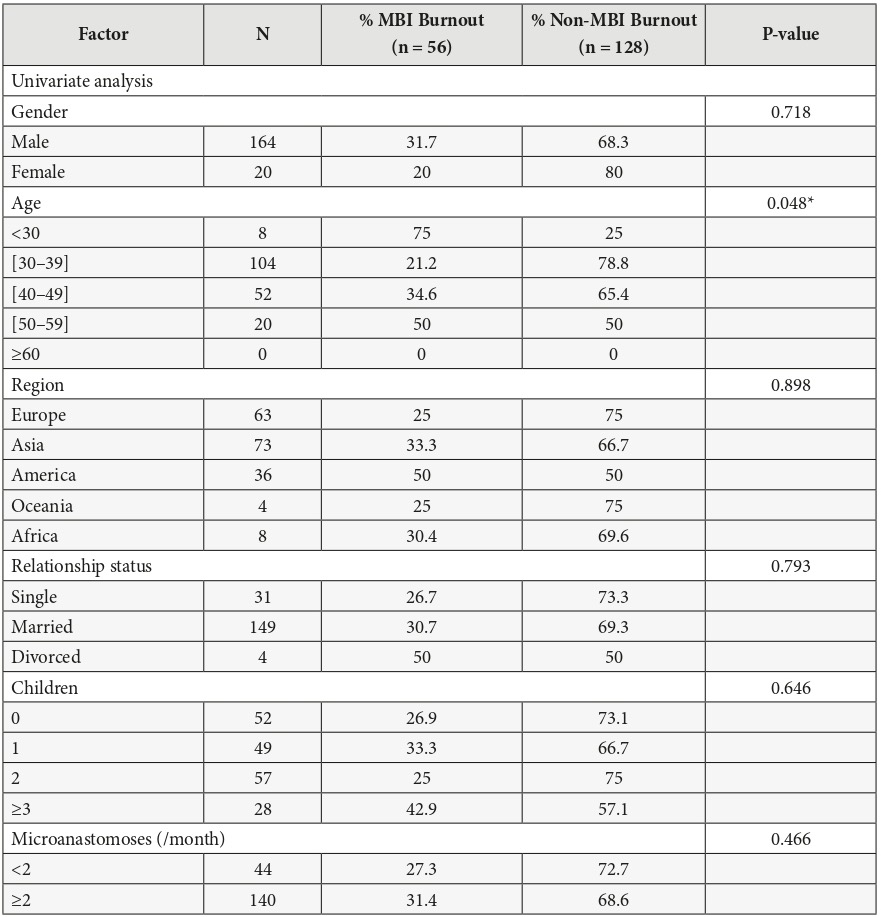

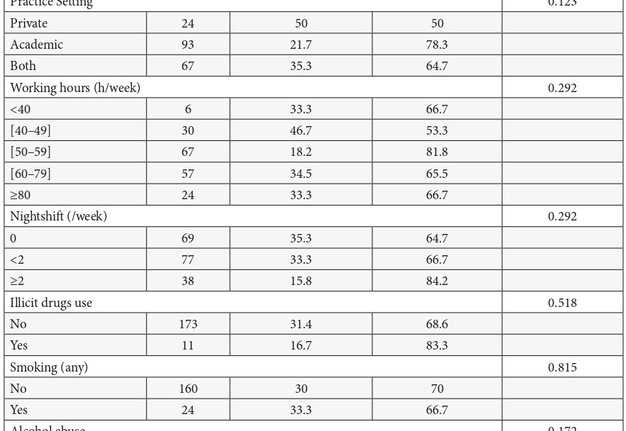

The demographic characteristics of participants relative to all 184 physicians were summarized in the left part of Table 1. The vast majority were male physicians (male: 89.13 percent; female: 10.87 percent), coming from all over the world, with a large tendency towards Europe and Asia (73.91 percent). Approximately 89 percent of participants were age 49 or younger. Over 80 percent of responders were married or had a partner. Approximately only 2 percent indicated that they had previously gone through a divorce, and 72.8 percent had children. Most of responders had been working as plastic surgeons (84.8 percent), around 60 hours per week, were on call approximately 1 night per week and exercised once or twice a week. The average number of microanastomoses performed per month was a minimum of two for 76.1 percent of the participants (group 1). Over half of the responders were in academic practice only, with 13 percent in private practice, and approximately 37 percent in both. A low percentage of the participants were concerned with the use of illicit drugs (2.2 percent), smoking (13 percent) and alcohol abuse (6.5 percent).

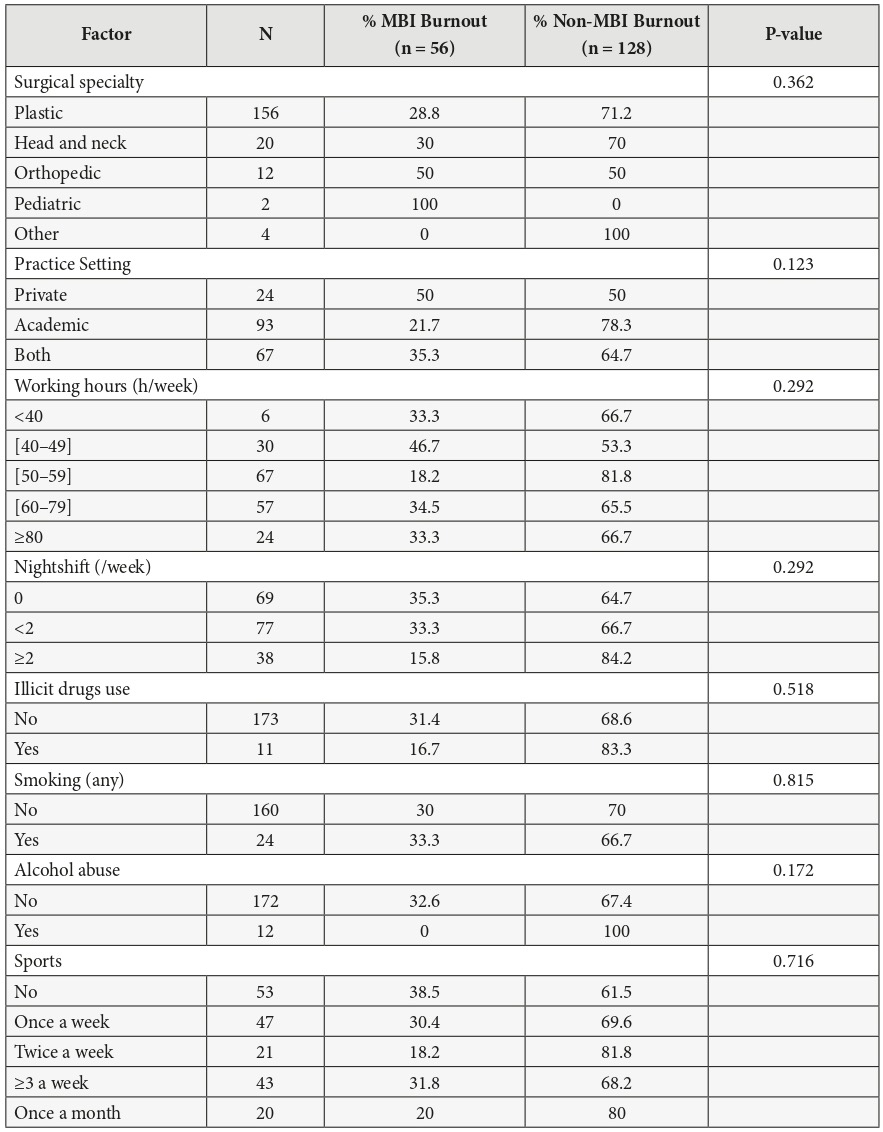

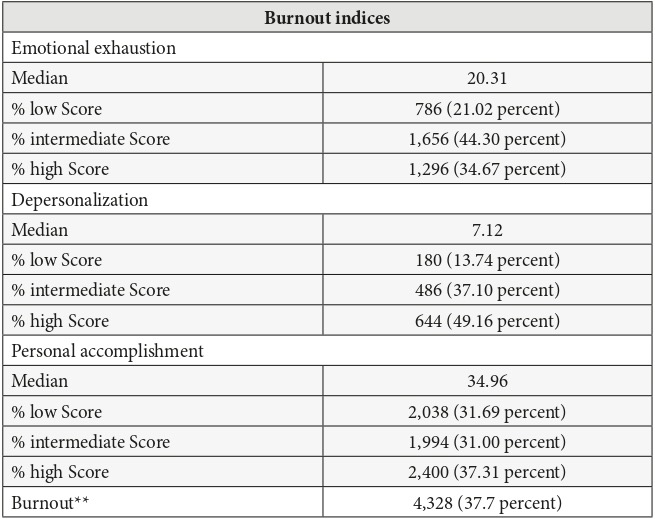

TABLE 2. Physician Burnout using the full Maslach Burnout Inventory Scale (MBI*)

* As assessed using the full Maslach Burnout Inventory. Per the standard scoring of the MBI for health care workers, physicians with scores of 27 on the Emotional Exhaustion subscale, 10 on the Depersonalization subscale, or 33 on the Personal Accomplishment subscale are considered to have a high degree of burnout in that dimension.

** High score on Emotional Exhaustion and/or Depersonalization subscales of the Maslach Burnout Inventory.

Rates of burnout, symptoms of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment were summarized in Table 2. When assessed using the full MBI categories, 34.67 percent of microvascular surgeons had high emotional exhaustion, 49.16 percent high depersonalization, and 31.69 percent a low sense of personal accomplishment in our study. In aggregate, 37.7 percent of the surgeons had at least one symptom of burnout based on a high emotional exhaustion score and/or a high depersonalization score.

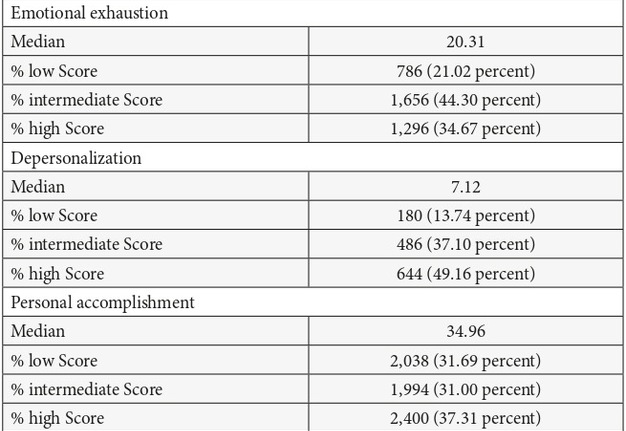

Univariate analysis of burnout status was summarized in the middle and right part of Table 1. It was compared to all independent variables of the study, and only one statistically significant set of results correlated to the age (p = 0.048) was found. However, burnout status was not correlated to the number of microanastomoses performed per month (p = 0.466) neither other variables we tested.

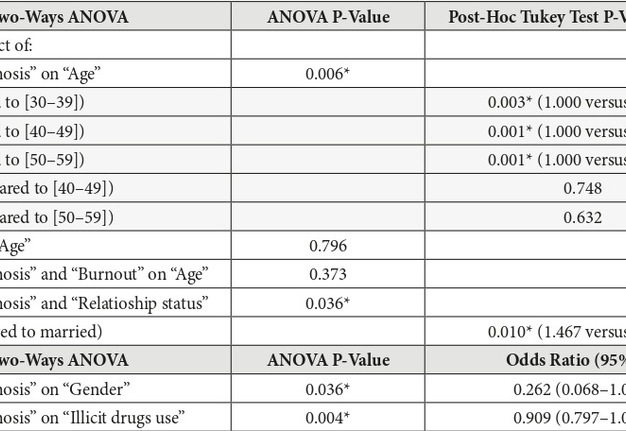

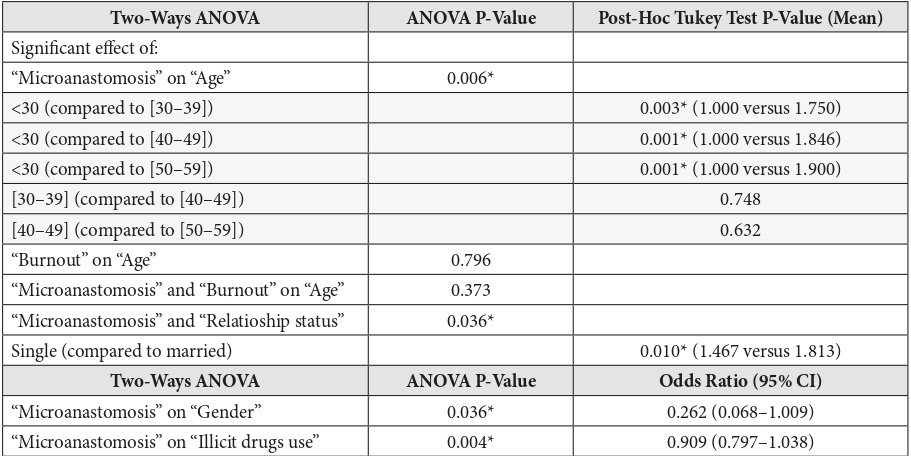

We next conducted a two-way ANOVA analysis presented in Table 3 to control for Type one error to remain at 5 percent with the identification of factors associated with “Number of Microanastomoses performed per month” and/or “Burnout Status.” Age, relationship status, gender and illicit drug use were independently associated with “Number of microanastomoses performed per month” only, but never with “Burnout Status” (p < 0.05). Therefore, when analyzing “Number of Microanastomoses performed per month” to “Age,” post-hoc test (ie, a Tukey`s test) found a superiority by means for all age groups compared to the group of age 30 and below, with a superiority of the group [50–59] (higher mean at 1.900). However, there were no difference between age groups [30–39] compared to [40–49] (p = 0.748) or age groups [40–49] compared to [50–59] (p = 0.632). For relationship status, we found that married microsurgeons were doing more microanastomoses compared to single microsurgeons (mean was 1.813 versus 1.467). Related to gender and illicit drug use, performing two or more microanastomoses per month was correlated with gender (p = 0.036) and illicit drugs use (p = 0.004). The odds of male to perform two and more microvascular anastomoses per month were about 4 times higher than those of woman (OR = 0.262, IC95% [0.068–1.009]), and there were no conclusion for illicit drug use odds (OR = 0.909, IC95% [0.797–1.038] close to 1).

DISCUSSION

Burnout is a troublesome situation among physicians, especially surgeons. Our findings suggest no relation between intensive microsurgery practice and higher burnout status among IMC Facebook group surgeons.

This international educative group allows microsurgeons to exchange ideas about clinical cases and collaborate on research. We used this group for our study population, as it is the biggest active group on microsurgery. Membership is quickly expanding, reaching over 7,000 members within the first 18 months after the group’s creation, and at the time of our survey it gathered over 11,500 members.9,10 In our study, participants may not be a representative study population to generalize conclusions as we were only able to gather 184 participants.

In our study, roughly one-third of the participants (37.7 percent) have symptoms of burnout, which is lower than what can be found in literature on surgical population (45.5 percent).11,19 This could be explained by our very low response rate under 2 percent, meaning that despite our best efforts to avoid this bias, we have probably selected the most active and passionate members of the group. One of the difficulties for many surgeons to identify burnout is that they love what they do, and passion makes an individual more resistant to burnout.20 Another explanation of this lower burnout proportion is about the IMC Facebook group itself: being in an active microsurgical international community where clinical cases can be easily discussed with worldwide experts could generates a sense of belonging and reassurance when a physician is in doubt and/or exposed to complications.

However, one-third of our participants have a “low score” regarding “Personal Accomplishment” (31.69 percent) in the MBI score, which is double than what can be seen in the literature (ranges between 11 to 17 percent).11 Personal Accomplishment measures feelings of competence and successful achievement in one's work with people, and lower scores correspond to greater experienced burnouts. Nguyen et al21 found that microvascular surgeons have one of the highest rates of gratification from their work compared to non-microvascular surgeons of the same specialty. Therefore, to explain our lower personal accomplishment ratio, it seems that being part of an international group using social media and focusing on microsurgical education allows its members to seek advice and special expertise in reconstructive surgery, and therefore attracts young or isolated surgeons. This particular subgroup of surgeons may have encountered previous complications in free flap surgery, motivating their participation on the IMC Facebook group.

Chaput et al22 demonstrated that amongst North American plastic surgeons, risk factors for burnout are excessive work (>70 hours of work per week, >2 nights of call per week), having a primarily reconstructive practice, a microsurgical or aesthetic subspecialty. Junior doctors and residents are also more likely to have burnout.22,23 Nevertheless, all our participants have a microsurgical and reconstructive practice; there is a vast majority of male and they are younger than in other studies.19,24 Participants are coming mostly from Europe and Asia, and they worked by mean less compared to Chaput et al’s burnout risk factors.22 Our univariate and multivariate analysis shows only a relationship between the younger age category and being a single surgeon to perform fewer microanastomoses per month than other age categories or marital status. Indeed, participants under 30 years old are mainly still in training and not married.

Burnout often coexists with alcohol and substance abuse.23 Surgeons with depression are more than seven times as likely to abuse alcohol.25 In our study, neither alcohol nor substance abuses are linked to burnout. Our participants are obviously looking to improve their physical health. The majority are exercising at least once or twice a week. Shanafelt et al26 found that those who exercised regularly had significantly higher overall and physical well-being score, and a lower prevalence of burnout (25 percent versus 30 percent). Therefore, our finding about not using illicit drugs seems rational in a group practicing physical activities on a regular basis, as it is in relationship with a higher number of microanastomoses performed per month.

The vast majority of the population of young surgeons in our study was male, which could be explained by the fact that this study was conducted in multiple countries where women still do not have the same access as men in surgical specialties. Indeed, this gender ratio is not comparable to other North American plastic surgeon group studies.11,24 Microsurgery’s “bad” reputation on impacting the surgeon’s quality of life, which motivated our work, could also be discussed as a reason for this gender discrepancy. However, we did not find any relationship between intensive practice of microsurgery and burnout, even stratified by gender. Indeed, Bennion and al27 found that maintenance of numerous microsurgical free flap caseloads is a protective factor for high levels of burnout among microvascular surgeons. We also find a lower proportion of divorced participants than in the general population (around 2 percent), with a majority of surgeons having children, which could indicate an important balance between family support and microsurgery practice.

Finally, our study shows that surgeons still in training especially need to be protected from burnout,24 as three quarters of our physicians under 30 have already experienced it. Maslach and Goldberg emphasized twenty years ago that responsibility for burnout prevention lays with the individual worker, and not the organization.28 Nevertheless, practice reorganization for residents such as weekly rounds with a senior surgeon and regular staff meetings are helping to prevent burnout.22,29,30 It is of importance when burnout rates among surgeons are expected to rise further over the next few years, as the demands of the surgical profession are only expected to increase. Indeed, supply of surgeons is stagnant worldwide, whereas the demand for surgery is increasing.31 Therefore, actively treating burnout by teaching young physicians how to avoid and recognize the first signs should be a requirement in all surgical programs.

CONCLUSIONS

Burnout status in IMC Facebook group surgeons was not correlated to the practice of microsurgery. As there is no counterpart group for a comparative study, no conclusion could be obtained from this work yet. However, we believe that being part of an international social media successful group could be a possible protective factor, especially for young or isolated surgeons worldwide, and an active participation could possibly improve education and protect microvascular surgeons by helping them to avoid and recognize burnout signs.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

DISCLOSURES

The authors have no financial interests in any of the products or techniques mentioned and have received no external support related to this study.

REFERENCES (31)

- Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, Dyrbye LN, Sotile W, Satele D, West CP, Sloan J, Oreskovich MR. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med 2012;172(18):1377–85. Crossref

- Maslach C, Leiter MP. Understanding the burnout experience: recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry 2016;15(2):103–11. Crossref

- Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Satele D, Sloan J, Freischlag J. Relationship between work-home conflicts and burnout among American surgeons: a comparison by sex. Arch Surg 2011;146(2):211–7. Crossref

- Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Dyrbye L, Bechamps G, Russell T, Satele D, Rummans T, Swartz K, Novotny PJ, Sloan J, Oreskovich MR. Special report: suicidal ideation among American surgeons. Arch Surg 2011;146(1):54–62. Crossref

- Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps GJ, Russell T, Dyrbye L, Satele D, Collicott P, Novotny PJ, Sloan J, Freischlag JA. Burnout and career satisfaction among American surgeons. Ann Surg 2009;250(3):463–71. Crossref

- Green A, Duthie HL, Young HL, Peters TJ. Stress in surgeons. Br J Surg 1990;77(10):1154–8. Crossref

- Bodin F, Dissaux C, Lutz JC, Hendriks S, Fiquet C, Bruant-Rodier C. The DIEP flap breast reconstruction: starting from scratch in a university hospital. Ann Chir Plast Esthet 2015;60(3):171–8. Crossref

- Pittenger AL. The use of social networking to improve the quality of interprofessional education. Am J Pharm Educ 2013;77(8):174. Crossref

- Chang TN, Hsieh F, Wang ZT, Kwon SH, Lin JA, Tang ET. Social media mediate the education of the global microsurgeons: the experience from International Microsurgery Club. Microsurgery 2018;38(5):596–7. Crossref

- Kwon SH, Goh R, Wang ZT, Tang ET, Chu CF, Chen YC, Lu JC, Wei CY, Hsu AT, Chang TN. Tips for making a successful online microsurgery educational platform: the experience of international microsurgery club. Plast Reconstr Surg 2019;143(1):221e–233e. Crossref

- Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sinsky C, Trockel M, Tutty M, Satele DV, Carlasare LE, Dyrbye LN. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2017. Mayo Clin Proc 2019;94(9):1681–94. Crossref

- Adam S, Mohos A, Kalabay L, Torzsa P. Potential correlates of burnout among general practitioners and residents in Hungary: the significant role of gender, age, dependant care and experience. BMC Fam Pract 2018;19(1):193. Crossref

- Maslach C, Jackson S, Leiter M. Maslach burnout inventory manual. 3rd ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996.

- Rafferty JP, Lemkau JP, Purdy RR, Rudisill JR. Validity of the Maslach Burnout Inventory for family practice physicians. J Clin Psychol 1986;42(3):488–92. Crossref

- Lee RT, Ashforth BE. A meta-analytic examination of the correlates of the three dimensions of job burnout. J Appl Psychol 1996;81(2):123–33. Crossref

- Thomas NK. Resident burnout. JAMA 2004;292(23):2880–9. Crossref

- Shanafelt TD, Bradley KA, Wipf JE, Back AL. Burnout and self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Ann Intern Med 2002;136(5):358–67. Crossref

- Rosen IM, Gimotty PA, Shea JA, Bellini LM. Evolution of sleep quantity, sleep deprivation, mood disturbances, empathy, and burnout among interns. Acad Med 2006;81(1):82–5. Crossref

- Khansa I, Janis JE. Growing epidemic: plastic surgeons and burnout – a literature review. Plast Reconstr Surg 2019;144(2):298e–305e. Crossref

- Norton J. The science of motivation applied to clinician burnout: lessons for healthcare. Front Health Serv Manage 2018;35(2):3–13. Crossref

- Nguyen PD, Herrera FA, Roostaeian J, Da Lio AL, Crisera CA, Festekjian JH. Career satisfaction and burnout in the reconstructive microsurgeon in the United States. Microsurgery 2015;35(1):1–5. Crossref

- Chaput B, Bertheuil N, Jacques J, Smilevitch D, Bekara F, Soler P, Garrido I, Herlin C, Grolleau JL. Professional burnout among plastic surgery residents: can it be prevented? Outcomes of a national survey. Ann Plast Surg 2015;75(1):2–8. Crossref

- Kuerer HM, Eberlein TJ, Pollock RE, Huschka M, Baile WF, Morrow M, Michelassi F, Singletary SE, Novotny P, Sloan J, Shanafelt TD. Career satisfaction, practice patterns and burnout among surgical oncologists: report on the quality of life of members of the Society of Surgical Oncology. Ann Surg Oncol 2007;14(11):3043–53. Crossref

- Streu R, Hansen J, Abrahamse P, Alderman AK. Professional burnout among US plastic surgeons: results of a national survey. Ann Plast Surg 2014;72(3):346–50. Crossref

- Merlo LJ, Singhakant S, Cummings SM, Cottler LB. Reasons for misuse of prescription medication among physicians undergoing monitoring by a physician health program. J Addict Med 2013;7(5):349–53. Crossref

- Shanafelt TD, Oreskovich MR, Dyrbye LN, Satele DV, Hanks JB, Sloan JA, Balch CM. Avoiding burnout: the personal health habits and wellness practices of US surgeons. Ann Surg 2012;255(4):625–33. Crossref

- Bennion DM, Dziegielewski PT, Boyce BJ, Ducic Y, Sawhney R. Fellowship training in microvascular surgery and post-fellowship practice patterns: a cross sectional survey of microvascular surgeons from facial plastic and reconstructive surgery programs. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2019;48(1):19. Crossref

- Maslach C, Goldberg J. Prevention of burnout: new perspectives. Appl Prev Psychol 1998;7(1):63–74. Crossref

- Chung RS, Ahmed N. How surgical residents spend their training time: the effect of a goal-oriented work style on efficiency and work satisfaction. Arch Surg 2007;142(3):249–52. Crossref

- McCue JD, Sachs CL. A stress management workshop improves residents’ coping skills. Arch Intern Med 1991;151(11):2273–7. Crossref

- Etzioni DA, Liu JH, Maggard MA, Ko CY. The aging population and its impact on the surgery workforce. Ann Surg 2003;238(2):170–7. Crossref