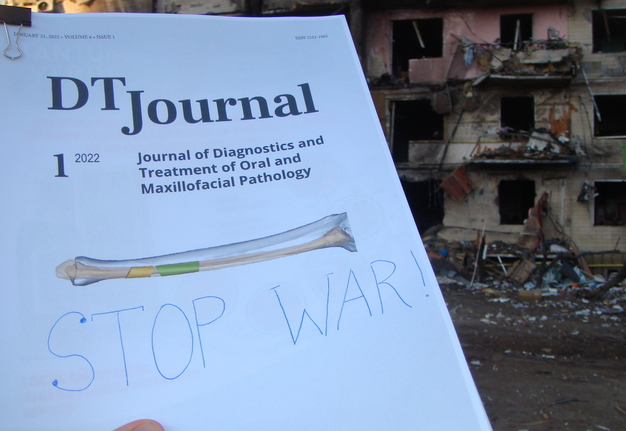

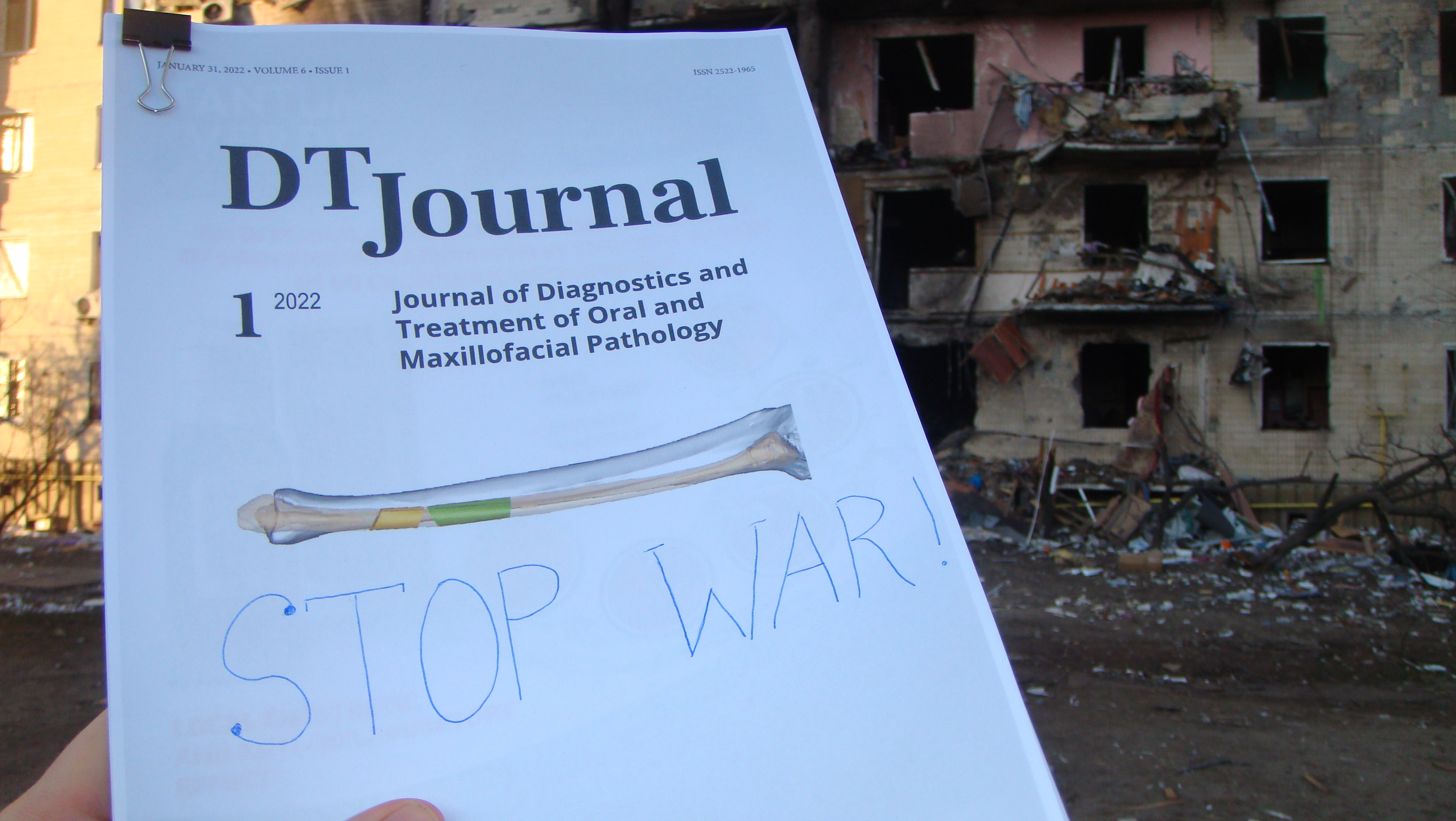

Stop the War! Europeans, Homes, Kindergartens, Hospitals, Universities, and Global Science Are under the Missiles!

February 28, 2022

https://doi.org/10.23999/j.dtomp.2022.2.3

J Diagn Treat Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2022;6:32–4.

Under a Creative Commons license

HOW TO CITE THIS ARTICLE

Fesenko II. Stop the war! Europeans, homes, kindergartens, hospitals, universities, and global science are under the missiles. J Diagn Treat Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2022;6(2):32–4.

NATIONAL REPOSITORY OF ACADEMIC TEXTS

https://nrat.ukrintei.ua/en/searchdoc/2022U000176/

INSTITUTIONAL REPOSITORY

https://ir.kmu.edu.ua/handle/123456789/619

EDITORIAL

He refuses US offer to evacuate, saying “I need ammunition, not a ride.”1

–Volodymyr Zelenskiy

6th President of Ukraine

5:00 a.m. of February 24, 2022… The citizens of peacefully sleeping Kyiv woke up from several powerful explosions. Russia insidiously attacked our beloved capital, flashed in our heads. The announced USA intelligence data published in recent reports2 turned out to be true, we thought. Quick internet news search revealed that similar explosions happened in other cities and villages of Ukraine―a European country with more than 40 million of citizens. Large-scale invasion of Russian troops and missile attacks, which were warned by world intelligence, began. Breaking news reported the invasion noted from the multiple border sides―the territory of Belarus, Russia, and temporary occupied Crimean peninsula.3,4

The multiple deaths of civilians, children, and the military, the shelling of hospitals, kindergartens, multi-storey residential buildings, and missile strikes on critical infrastructure are not a complete list of all Russian war crimes against humanity which have been recorded during the last five days of February.5 And today, at evening of February 28, 2022, we are noticing how the life of all Ukrainians is changed forever. Five days of military resistance of our phenomenally brave Ukrainian defense forces against Russian occupants clearly showed the enemy how strong is the spirit of Ukrainians and the state political apparatus. International support of Ukraine and sanctions being imposed on Russia by civilized countries continues to grow making a significant pressure on Russian Federation to stop the war.6

One of the missile attack7 happened (Fig 1) in the close distance to the editorial office (EO) of our journal and homes of editorial board (EB) members. That is why we can say that the words “global science is under the missiles” are not just a figure of speech, but the real state of things. Nevertheless, the acquired skills of our EO during Covid-19 pandemic to work remotely8,9 helped us in this war situation. Of course saving lives of our workers and partners is a top priority. But payment of the salaries (for the possibility to buy a food, gasoline, etc.), and taxes (to support our military and government) also became a first line goals for us. Moreover, in this nightmare situation the wartime can force us to be not only the editors of a scientific journal, but essentially military correspondents.

The academic oral and maxillofacial surgeons (OMSs) who are working in Kyiv clinical hospitals became also involved into the urgent wartime surgical cases―ballistic and explosive trauma, etc. The role of OMSs in wartime are well described by Strother (2003),10 Haug (2005),11 Hussey (2014)12, and others13. Furthermore, Haug (2005) united the opinions of professionals in a special issue dedicated to maxillofacial surgery in emergencies, wartime, and during the terrorist attacks.11 Among their topics are: (1) tissue injury and healing,14 (2) features of ballistic injuries,15 (3) blood substitutes: hemoglobin-based oxygen carriers,16 (4) acute management of facial burns,17 (5) distribution of maxillofacial injuries in terrorist attacks,18 (6) improvised explosive devices and the oral and maxillofacial surgeon,19 (7) radiation injuries, triage, and treatment after a nuclear terrorist attack,20 (8) bioterrorism and biologic warfare,21 (9) penetrating, perforating, and avulsive fragmentation injuries,22 and (10) maxillofacial trauma treatment protocol23. Numerous ballistic trauma textbooks24 and book chapters25,26 are also more than useful for OMSs involved into a war cases management.

In sum, the wartime forced us not only to refocus on military trauma, but also to immediately change the content of the journal. That is why the EB is inviting submission the manuscripts focused on ballistic and explosion head and neck trauma. We believe that publication of modern management developments in such wartime chapter of oral and maxillofacial surgery will assist surgeons to apply immediately new techniques and approaches in the Ukrainian hospitals and abroad.

The true soldier fights not because he hates what is in front of him, but because he loves what is behind him.

―Gilbert K. Chesterton

An English writer

REFERENCES (26)

- Braithwaite S. Zelensky refuses US offer to evacuate, saying 'I need ammunition, not a ride' [document on the internet]; 26 Feb 2022 [сited 28 Feb 2022]. Available from: Link

- Pilkington E. US intelligence believes Russia has ordered Ukraine invasion – reports [document on the internet]; 20 Feb 2022 [сited 28 Feb 2022]. Available from: Link

- Zinets N, Vasovic A. Missiles rain down around Ukraine [document on the internet]; 25 Feb 2022 [сited 28 Feb 2022]. Available from: Link

- Wu J, Carman J, Einhorn E, Hersher M. Ukraine attacked: map of sites targeted by Russia’s invasion [document on the internet]; 25 Feb 2022 [сited 28 Feb 2022]. Available from: Link

- Kossov I. Russia’s war on Ukraine: where fighting is on now (Feb. 27 live updates) [document on the internet]; 27 Feb 2022 [сited 28 Feb 2022]. Available from: Link

- Henley J. What sanctions have been imposed on Russia over Ukraine invasion? [document on the internet]; 28 Feb 2022 [сited 28 Feb 2022]. Available from: Link

- Klochko N. Night attack on Kyiv: the Kyiv City State Administration reported the number of victims [document on the internet]; 25 Feb 2022 [сited 28 Feb 2022]. Available from: Link

- Kilipiris EG. The covid-19 pandemic and the dtjournal.org. J Diagn Treat Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2020;4(9):179–80. Crossref | Google Scholar

- Tymofieiev OO, Ushko NO, Yarifa MO. Сovid-2019 response: virtual educational process at the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery using Google Classroom. J Diagn Treat Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2020;4(3):51–2. Crossref | Google Scholar

- Strother EA. Maxillofacial surgery in World War I: the role of the dentists and surgeons. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2003;61(8):943–50. Crossref | Medline | Google Scholar

- Haug RH. The role of the oral and maxillofacial surgeon in wartime, emergencies, and terrorist attacks. Oral Maxillofacial Surg Clin North Am 2005;17(3):ix–x. Crossref

- Hussey KD. British dental surgery and the First World War: the treatment of facial and jaw injuries from the battlefield to the home front. Br Dent J 2014;217(10):597–600. Crossref | Medline | Google Scholar

- Holmes S, Coombes A, Rice S, Wilson A; Barts and the London NHS Trust. The role of the maxillofacial surgeon in the initial 48 h following a terrorist attack. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2005;43(5):375–82. Crossref | Medline | Google Scholar

- Kincaid B, Schmitz JP. Tissue injury and healing. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 2005;17(3):241–50. Crossref | Medline | Google Scholar

- Powers DB, Robertson OB. Ten common myths of ballistic injuries. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 2005;17(3):251–9. Crossref | Medline | Google Scholar

- Fitzpatrick CM, Kerby JD. Blood substitutes: hemoglobin-based oxygen carriers. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 2005;17(3):261–6. Crossref | Medline | Google Scholar

- Bagby SK. Acute management of facial burns. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 2005;17(3):267–72. Crossref | Medline | Google Scholar

- Hasson O. Distribution of maxillofacial injuries in terrorist attacks. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 2005;17(3):273–80. Crossref | Google Scholar

- Goksel T. Improvised explosive devices and the oral and maxillofacial surgeon. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 2005;17(3):281–7. Crossref | Medline | Google Scholar

- McGhee RK, Praetzel DC, Medley CC. Radiation injuries, triage, and treatment after a nuclear terrorist attack. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 2005;17(3):289–98. Crossref | Google Scholar

- Bourgeois SL Jr, Doherty MJ. Bioterrorism and biologic warfare. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 2005;17(3):299–330. Crossref | Medline | Google Scholar

- Will MJ, Goksel T, Stone CG Jr, Doherty MJ. Oral and maxillofacial injuries experienced in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom I and II. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 2005;17(3):331–9. Crossref | Medline | Google Scholar

- Powers DB, Will MJ, Bourgeois SL Jr, Hatt HD. Maxillofacial trauma treatment protocol. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 2005;17(3):341–55. Crossref | Medline | Google Scholar

- Pryor JP, Cotton B. Neck injury. In: Mahoney PF, Ryan JM, Brooks AJ, William Schwab C, editors. Ballistic trauma. London: Springer, 2005:209–40. Crossref

- Tymofieiev OO. Manual of maxillofacial and oral surgery [in Russian]. 5th ed. Kyiv: Chervona Ruta-Turs; 2012.

- Holmes JD. Gunshot injuries. In: Miloro M, Ghalia GE, Larsen PE, Waite PD. Peterson’s principles of oral and maxillofacial surgery, 2nd ed., Volumes I and II. Hamilton, Ontario: B. C. Decker, Inc., 2004:509–26.