Perioperative Management for Microvascular Free Tissue Transfer for Head and Neck Reconstruction – Commentary

September 5, 2024

J Diagn Treat Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2024;8: 100287.

DOI: 10.23999/j.dtomp.2024.9.100287

Under a Creative Commons license

HOW TO CITE THIS ARTICLE

Le JM, Ponto J, Yedeh YP, Morlandt AB. Perioperative management for microvascular free tissue transfer for head and neck reconstruction – commentary. J Diagn Treat Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2024 Sep;8(9):100287. https://doi.org/10.23999/j.dtomp.2024.9.100287

NATIONAL REPOSITORY OF ACADEMIC TEXTS

https://nrat.ukrintei.ua/en/searchdoc/2024U000186/

SUMMARY. SUMMARY IN UKRAINIAN (PDF).

Le et al. provided a comprehensive commentary on perioperative management for head and neck oncologic patients undergoing microvascular reconstructive surgery. This commentary is based on a detailed review and consensus statements from the Society for Head and Neck Anesthesia (SHANA), an international organization dedicated to enhancing perioperative care for these patients. The consensus statement, published in 2021 by Healy et al., addressed preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative considerations to optimize clinical outcomes. It included 14 statements from 16 SHANA members across 11 institutions, following two rounds of literature reviews.

The commentary emphasized the importance of preoperative nutrition optimization, tobacco cessation, and early recognition of alcohol withdrawal symptoms. In the intraoperative phase, key aspects such as airway management in cases of extensive tumor burden (including awake fiberoptic intubation and tracheostomy), fluid management, hemodynamic monitoring, and multimodal analgesia were briefly discussed. Notably, vasopressors can be used to optimize hemodynamic management without compromising flap perfusion. Additionally, careful fluid resuscitation is crucial to avoid fluid overload, which could increase the risk of flap failure. Multimodal pain management strategies were highlighted, including inhalational anesthetics, anti-inflammatories, narcotics, and regional anesthesia.

In the postoperative period, effective communication between healthcare provider teams is essential. Airway management was linked to three of the five consensus statements, underscoring the need for clear and concise communication between the anesthesia and surgical teams. This includes coordinating ventilatory support weaning, extubation planning, and preparation for reintubation if necessary. Such measures help reduce intensive care unit (ICU) utilization, minimize airway-related adverse events, and shorten the length of hospitalization.

Overall, the commentary hopes to serve as a guide for multidisciplinary head and neck oncology units across all international centers in managing this complex patient population.

KEY WORDS

Head and neck oncology, microvascular surgery, head and neck anesthesia, perioperative management.

Edited by: Ievgen Fesenko, Kyiv Medical University, Ukraine.

Reviewed by: Anastasiya Quimby, Good Samaritan Hospital, AQ Surgery: Head and Neck, Microvascular Surgery Institute, USA and Laurent Ganry, Long Island Jewish Medical Center, USA.

ARTICLE

Perioperative management of adult patients undergoing head and neck microvascular reconstructive surgery varies among anesthesiologists and institutions. Due to the medical and surgical complexities associated with this patient population, various perioperative management protocols have been described to improve clinical outcomes starting from the initial preoperative clinic visit until the early postoperative outpatient clinic visit. These protocols have been coined as the term “Enhanced Recovery After Surgery” or ERAS and were first applied in the field of colorectal surgery, followed by additional surgical specialties (e.g., breast, spine, gynecologic, and orthopedics), and more recently major head and neck surgery [1, 2]. Regarding microvascular reconstructive head and neck surgery, advancements in surgical techniques and perioperative monitoring of the flap have resulted in decreased surgical complications and greater flap success rates [3, 4]. In addition to innovations from the surgical perspective, optimizing perioperative care for these surgical patients improves clinical outcomes and decreases hospitalization, healthcare costs, and utilization of resources. This is a commentary on an article published by the Society for Head and Neck Anesthesia in 2021 highlighting the multidisciplinary management of the head and neck patient.

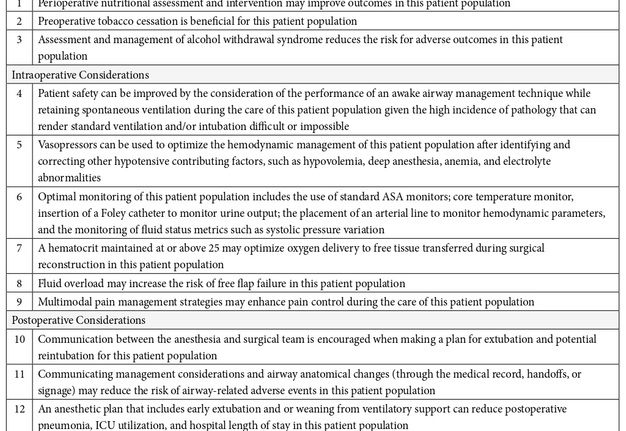

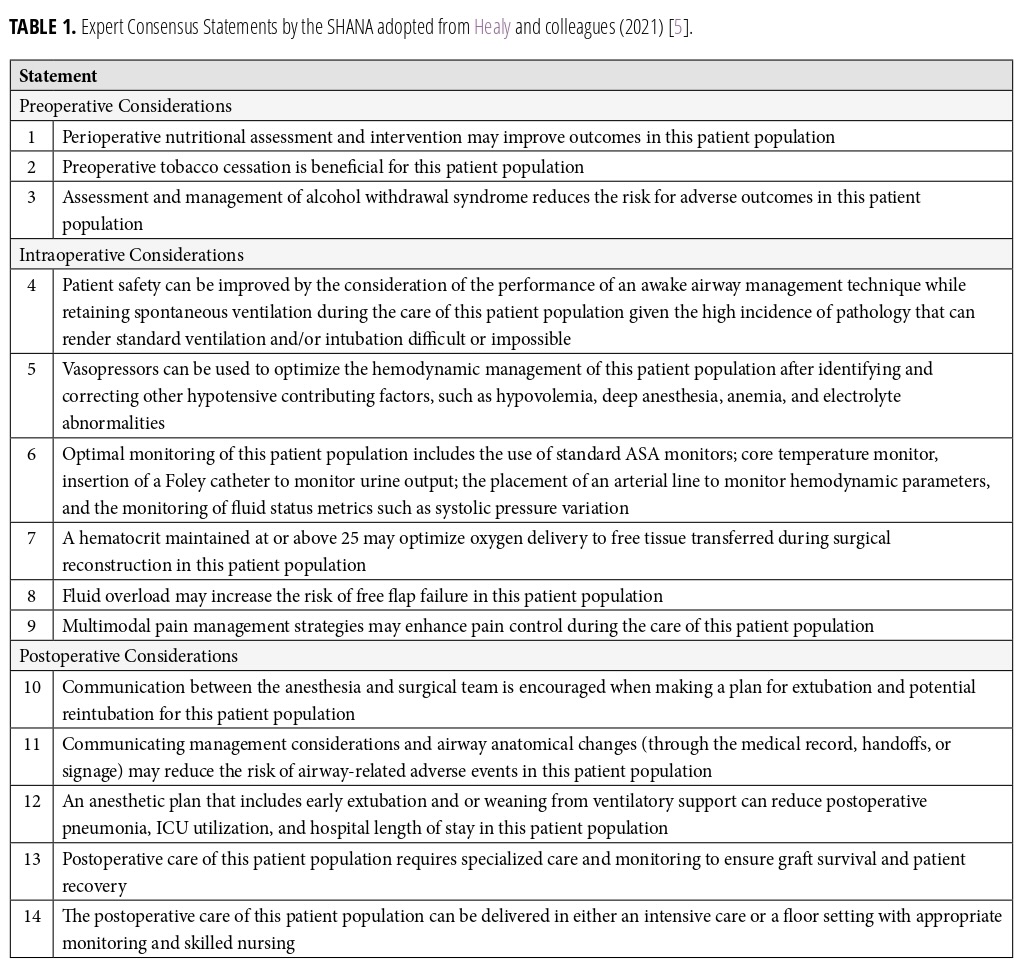

In 2021, Healy and colleagues conducted an extensive review of the literature and released an expert consensus statement on the perioperative management of adult patients undergoing microvascular free tissue reconstruction of the head and neck from the Society for Head and Neck Anesthesia (SHANA) [5]. In this article, the authors highlight the challenges in the perioperative and anesthesia care of this patient population as they generally present with multiple medical comorbidities (e.g., advanced age, malnutrition, cardiovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, chronic pulmonary obstructive disease, kidney disease, reduced physical mobility, and more). Furthermore, common risk factors such as long-standing tobacco smoking and alcohol consumption are also present in this patient population and negatively impact clinical outcomes during the perioperative period (e.g., wound healing complications and alcohol withdrawal) and prolong hospitalization. The authors state that there remains little guidance to optimize care; and as a result, the training experience of the practitioner(s) has been the general institutional culture which varies among institutions. To address this variability in care, the leadership of SHANA elected 16 of its members, representing 11 institutions to develop guidance supported by clinical evidence and expertise using a modified Delphi Method. The members then developed focused topic questions following two rounds of literature reviews. The first literature search identified clinical practice guidelines, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and review articles related to the subject population. The second literature search identified randomized controlled trials and observational studies related to the focused questions based on the initial literature search. This resulted in 14 consensus statements grouped by phase of care (preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative). In this commentary, we will highlight the statements that we feel are most relevant in guiding the postoperative management of the head and neck patient, Table 1.

Of the 14 statements, 3 were associated with the preoperative setting. Firstly, nutritional assessment and optimization can lead to improved outcomes in this population. Most patients present with malnutrition due to poor oral intake associated with tumor burden involving the airway and masticatory organs. Alternative means for enteral feeding that bypasses the oral cavity such as a gastrostomy tube should be considered in the preoperative planning phase. Secondly, tobacco cessation before surgery can improve both the patient’s health and well-being as well as flap outcome. Finally, assessment for alcohol withdrawal syndrome is important to avoid adverse events postoperatively. In our practice, preoperative nutrition optimization is very important. For patients with advanced-stage tumors and sarcopenia, enteral access via gastrostomy tube placement is often performed at the time of the ablative and reconstructive surgery to permit sufficient short and long-term nutritional intake while the patient undergoes adjuvant therapy and dysphagia therapy.

Intraoperatively, optimal monitoring of the patient includes standard ASA monitors such as core temperature, noninvasive and invasive blood pressure, pulse oximetry, electrocardiogram, and urine output. This can allow for appropriate fluid management and resuscitation to avoid fluid overload, support hemodynamic changes, and avoid vasopressors as necessary to avert vasoconstrictive changes that may affect flap success rates. While there is a tendency to avoid the use of vasopressors to prevent potential free flap complications, the literature has consistently shown that intraoperative use of vasopressors is safe in microvascular reconstructive surgery [6–9]. Finally, the incorporation of multimodal pain management can improve pain control and decrease the risk of opioid dependence. Studies have described the implementation of scheduled non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), acetaminophen, muscle relaxants (e.g., methocarbamol), and anticonvulsants (e.g., gabapentin) to reduce the total opioid consumption [10]. Some have shown promising results with regional analgesia via nerve blocks [11, 12]. In addition, multimodal analgesia such as regional anesthesia and the use of dexmedetomidine has been shown to reduce perioperative opioid consumption and potential surgical site complications in the early postoperative period [11, 13].

Notably, four statements were associated with airway management in the intraoperative and postoperative phases of care. This involved a thorough preoperative airway assessment using radiologic and endoscopic visualization in preparation for airway management following induction of anesthesia. Standard airway management, such as masking or intubation, may be more challenging due to altered airway anatomy in these patients, secondary to the tumor burden, trismus, or prior procedures. In these cases, an awake fiberoptic intubation or tracheotomy while retaining spontaneous ventilation can improve patient safety. In the postoperative phase, communication among the surgical, anesthesia, and postoperative care teams emphasizes the importance of ventilatory support weaning, safe extubation, and tracheostomy decannulation to reduce the risk for postoperative pneumonia, intensive care unit (ICU) utilization, and length of hospitalization stay. Furthermore, close postoperative monitoring in the specialized care unit (“step-down unit”) or ICU is appropriate to ensure free flap success rates and patient recovery. The decision to perform an elective tracheotomy versus delayed extubation in this patient population remains up for debate and varies across institutions. Several classification systems have been described to guide the surgeon in determining which patients would require a tracheotomy to decrease the risk of an adverse airway event [14-16]. In our practice, we will generally perform a tracheostomy in patients who have composite resection of the mandible and near total glossectomy, bilateral neck dissection, and have a large body habitus (BMI >30). Furthermore, all patients undergoing free tissue transfer for head and neck reconstruction will go to a dedicated specialized care unit (non-ICU) for postoperative monitoring. The nursing staff are well trained in managing tracheostomy patients and monitoring free flaps.

In conclusion, the perioperative management of adult patients undergoing microvascular free tissue reconstruction of the head and neck is multifaceted, influenced by surgical advancements and comprehensive care protocols. The implementation of ERAS principles, initially developed for colorectal surgery and subsequently adapted to various surgical specialties, including head and neck surgery, underscores the importance of optimizing perioperative care to improve clinical outcomes. Complex medical comorbidities and lifestyle factors characterize the challenges inherent in managing this patient population. These necessitate a tailored approach to perioperative care. Incorporating evidence-based practices and interdisciplinary collaboration, informed by the SHANA consensus statement, facilitates a standardized approach while accommodating individual needs. By striving for excellence in perioperative care, healthcare providers can minimize complications, reduce hospitalization, and optimize patient outcomes within the context of head and neck microvascular reconstructive surgery.

Acknowledgments: None.

Statements and Declarations: The authors have no financial or non-financial interests that are directly or indirectly related to the work submitted for publication.

REFERENCES (16)

-

Ljungqvist O, Scott M, Fearon KC. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery: A Review. JAMA Surg. 2017 Mar 1;152(3):292-298. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2016.4952

-

Dort JC, Farwell DG, Findlay M, et al. Optimal Perioperative Care in Major Head and Neck Cancer Surgery With Free Flap Reconstruction: A Consensus Review and Recommendations From the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Society. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017 Mar 1;143(3):292-303. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2016.2981

-

Shen AY, Lonie S, Lim K, et al. Free Flap Monitoring, Salvage, and Failure Timing: A Systematic Review. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2021 Mar;37(3):300-308. doi: https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1722182

-

Markey J, Knott PD, Fritz MA, Seth R. Recent advances in head and neck free tissue transfer. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015 Aug;23(4):297-301. https://doi.org/10.1097/moo.0000000000000169

-

Healy DW, Cloyd BH, Straker T, et al. Expert Consensus Statement on the Perioperative Management of Adult Patients Undergoing Head and Neck Surgery and Free Tissue Reconstruction From the Society for Head and Neck Anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2021 Jul 1;133(1):274-283. https://doi.org/10.1213/ane.0000000000005564

-

Harris L, Goldstein D, Hofer S, Gilbert R. Impact of vasopressors on outcomes in head and neck free tissue transfer. Microsurgery. 2012 Jan;32(1):15-9. https://doi.org/10.1002/micr.20961

-

Goh CSL, Ng MJM, Song DH, Ooi ASH. Perioperative Vasopressor Use in Free Flap Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2019 Sep;35(7):529-540. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0039-1687914

-

Swanson EW, Cheng HT, Susarla SM, et al. Intraoperative Use of Vasopressors Is Safe in Head and Neck Free Tissue Transfer. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2016 Feb;32(2):87-93. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1563381

-

Fang L, Liu J, Yu C, et al. Intraoperative Use of Vasopressors Does Not Increase the Risk of Free Flap Compromise and Failure in Cancer Patients. Ann Surg. 2018 Aug;268(2):379-384. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000002295

-

Go BC, Go CC, Chorath K, et al. Multimodal Analgesia in Head and Neck Free Flap Reconstruction: A Systematic Review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022 May;166(5):820-831. https://doi.org/10.1177/01945998211032910

-

Le JM, Gigliotti J, Sayre KS, et al. Supplemental Regional Block Anesthesia Reduces Opioid Utilization Following Free Flap Reconstruction of the Oral Cavity: A Prospective, Randomized Clinical Trial. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2023 Feb;81(2):140-149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2022.10.015

-

Cowgill AE, Womack J, Powell L. Multi-site nerve block catheters for postoperative analgesia in extended scapulectomy and free-flap reconstruction. Anaesth Rep. 2022 Oct 14;10(2):e12188. https://doi.org/10.1002/anr3.12188

-

Le JM, Morlandt AB, Patel K, et al. Is the Use of Dexmedetomidine Upon Emergence From Anesthesia Associated With Neck Hematoma Formation Following Head and Neck Microvascular Reconstruction? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2024 Aug;82(8):902-911. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2024.04.009

-

Cai TY, Zhang WB, Yu Y, et al. Scoring system for selective tracheostomy in head and neck surgery with free flap reconstruction. Head Neck. 2020 Mar;42(3):476-484. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.26028

-

Cameron M, Corner A, Diba A, Hankins M. Development of a tracheostomy scoring system to guide airway management after major head and neck surgery. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009 Aug;38(8):846-849. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2009.03.713

-

Gupta K, Mandlik D, Patel D, et al. Clinical assessment scoring system for tracheostomy (CASST) criterion: Objective criteria to predict pre-operatively the need for a tracheostomy in head and neck malignancies. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2016 Sep;44(9):1310-1313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcms.2016.07.008