Undiagnosed Factor V Leiden Presenting as Free Flap Thrombosis in Mandibular Reconstruction: A Case Report

Published October 01, 2025

J Diagn Treat Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2025; 9: 100311.

DOI: 10.23999/j.dtomp.2025.10.100311

Under a Creative Commons license (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

HOW TO CITE THIS ARTICLE

Thornton B, Rothman N, Patel K, Kase MT, Morlandt AB, Ponto J. Undiagnosed factor V Leiden presenting as free flap thrombosis in mandibular reconstruction: A case report. J Diagn Treat Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2025 Oct;9(10):100311. https://doi.org/10.23999/j.dtomp.2025.10.100311

Summary

Microvascular free flap reconstruction remains the gold standard for repairing complex head and neck defects, yet vascular thrombosis continues to pose a serious threat to flap viability. Flap failure is often attributed to technical or local factors; however, the contribution of underlying hypercoagulable states is frequently underrecognized. We present the case of a 71-year-old male with no personal or family history of thrombosis who developed both intraoperative and postoperative arterial and venous thromboses of a fibula free flap used for mandibular reconstruction following extirpation of squamous cell carcinoma. Flap loss led to hematologic evaluation, revealing previously undiagnosed heterozygous Factor V Leiden (FVL). The patient subsequently underwent successful contralateral fibula reconstruction using a modified anticoagulation regimen that included intraoperative heparin boluses and continuous postoperative heparin for therapeutic anticoagulation in intensive care. This case highlights the potential for occult thrombophilia to cause flap failure in the absence of technical error or thrombotic history. It underscores the need for individualized risk assessment and tailored perioperative planning in complex microsurgical reconstruction when there is clinical suspicion of systemic coagulopathic dyscrasia.

Keywords

Factor V, thrombophilia, free tissue flaps, myocutaneous flap, surgical flaps, head and neck neoplasms, squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck, neck dissection, mandibular reconstruction, mandibular neoplasms, venous thrombosis, arterial thrombosis, anticoagulants, plastic surgery procedures, oral surgical procedures, perioperative care, aspirin, heparin, case reports, review

Introduction

Microvascular free flap reconstruction is the standard of care for repairing complex head and neck defects following oncologic resection, with reported success rates of 90–95% [1-3]. Despite these favorable outcomes, flap failure due to vascular thrombosis—most commonly venous—remains a serious complication, leading to functional deficits, prolonged hospitalization, increased healthcare costs, and delays in adjuvant therapy [4-6]. While technical and perioperative factors are typically scrutinized, the role of underlying hypercoagulability is often underrecognized [7-9].

Factor V Leiden (FVL) is the most prevalent inherited thrombophilia, particularly among Caucasian populations, with heterozygous carriage in approximately 3–8% [10]. The Arg506Gln mutation in the F5 gene renders factor V resistant to inactivation by activated protein C, impairing physiologic anticoagulant mechanisms and increasing thrombotic risk, by 3- to 8-fold in heterozygotes and up to 80-fold in homozygotes [11-12]. Despite its frequency, the impact of FVL on free flap outcomes in head and neck microsurgery remains poorly characterized. Existing literature is limited to small case series or individual reports, often involving patients with a prior diagnosis of thrombophilia [15-16]. The absence of standardized perioperative anticoagulation protocols for these patients has contributed to significant variability in clinical management [15-17].

We present a case of early free flap failure due to both arterial and venous thromboses in a patient ultimately found to have previously undiagnosed heterozygous FVL. The patient underwent successful contralateral fibula free flap reconstruction using a modified anticoagulation protocol. This case highlights the importance of considering occult thrombophilia in unexplained flap failure and demonstrates how adaptive perioperative strategies can mitigate risk in subsequent reconstruction.

Case Report

A 71-year-old male with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, cardiac arrhythmia, and prior laryngeal carcinoma was referred to the UAB Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery department in July 2024 after presenting to his general dentist with complaints of loose teeth. His oncologic history included a cordectomy, suspension laryngectomy, and adjuvant radiotherapy (66 Gy) administered between 2019 and 2021. The radiation field was confined to the larynx and did not include nodal mapping or elective neck irradiation. He had no personal or family history of venous thromboembolism (VTE).

Biopsy of the mandibular gingiva and computed tomography (CT) imaging were consistent with cT4aN2bM0 squamous cell carcinoma of the anterior mandible. Following multidisciplinary tumor board review, the patient elected to proceed with composite resection and immediate reconstruction.

A left neck dissection (levels Ia, Ib, IIa, IIb, III, IV, and V) was performed followed by segmental mandibulectomy. The defect was reconstructed with a three-segment fibula free flap incorporating an 8×12 cm skin paddle. No boluses of low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) or unfractionated heparin (UFH) were given prior to the initial microvascular anastomosis attempt. Papaverine was applied to the recipient vessels to promote vasodilation. During microvascular anastomosis, both arterial and venous connections thrombosed repeatedly. The initial attempt to anastomose the flap’s vena comitans to the left common facial vein and the flap’s artery to the left facial artery resulted in rapid thrombosis. A subsequent arterial anastomosis to the left lingual artery also thrombosed shortly after creation. Multiple re-anastomoses were required before adequate flow was established in the left lingual artery. A bolus of intravenous UFH was administered after initial thrombus formation was observed, and the flap was flushed directly with heparinized saline after each failed anastomosis. No streptokinase was used.

Satisfactory perfusion was confirmed intraoperatively by Doppler signal and capillary refill. Postoperatively, fluid balance and hydration status were closely monitored, and normothermia was maintained. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) protocol was followed. Weight-based LMWH (0.4-0.5 mg/kg twice daily) was given but acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) was not due to early flap failure.

On postoperative day one, flap monitoring revealed loss of Doppler signal and flap pallor. Emergent re-exploration demonstrated both arterial and venous thrombosis at the anastomosis sites. Despite systemic heparinization and multiple attempts at thrombectomy, catheterization, and revision anastomosis, the flap could not be salvaged and was abandoned. The neck wound was closed, and alternative reconstructive options were discussed with the patient and his family.

Given the rapid and unexplained thrombotic failure, hematology was consulted. Initial laboratory testing revealed abnormal activated protein C resistance, raising strong suspicion for an underlying thrombophilia. Due to the functional and oncologic implications of delaying reconstruction, the full hematologic workup was not yet complete at the time of the second fibula free flap. The patient was therefore managed under the working assumption that he likely possessed coagulopathy. Genetic testing later confirmed a heterozygous FVL mutation.

Ten days after the initial reconstruction attempt, a second free flap procedure was performed using the contralateral fibula, as the size of the defect was deemed incompatible with functional recovery and timely initiation of adjuvant radiation therapy. A bolus of 5,000 units of intravenous UFH was administered prior to the initial microvascular anastomosis attempt. The anastomosis utilized the right facial artery for simpler access despite increased morbidity associated with crossing the midline. This first anastomosis developed clotting and required revision. After thrombosis was observed, the flap was flushed directly with heparinized saline, and an additional 5,000 units of UFH was administered to achieve a supratherapeutic activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) of approximately 200 seconds. The second anastomosis attempt was then successfully completed. Postoperatively, intravenous UFH infusion was initiated and continued for three days in the intensive care unit (ICU), with dosing adjusted to maintain an aPTT target of 100 seconds. The ERAS protocol was followed, and hourly flap monitoring was maintained throughout the hospital stay. On post-operative day four, the patient was transitioned to weight-based LMWH dosing and subsequently to fixed dose LMWH (30 mg twice daily) and ASA (325 mg daily via PEG tube) for VTE prophylaxis.

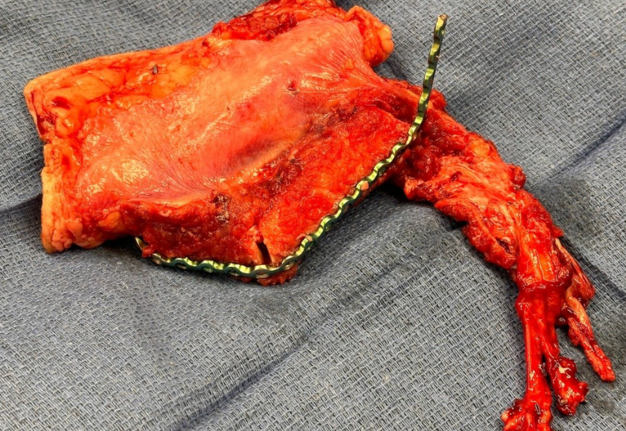

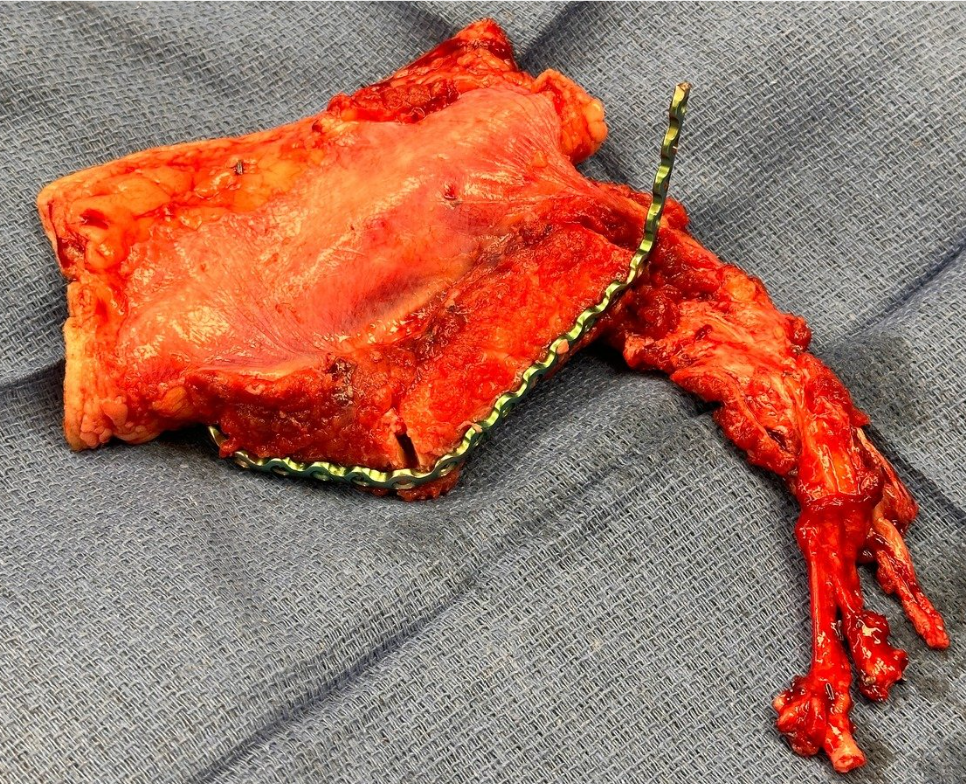

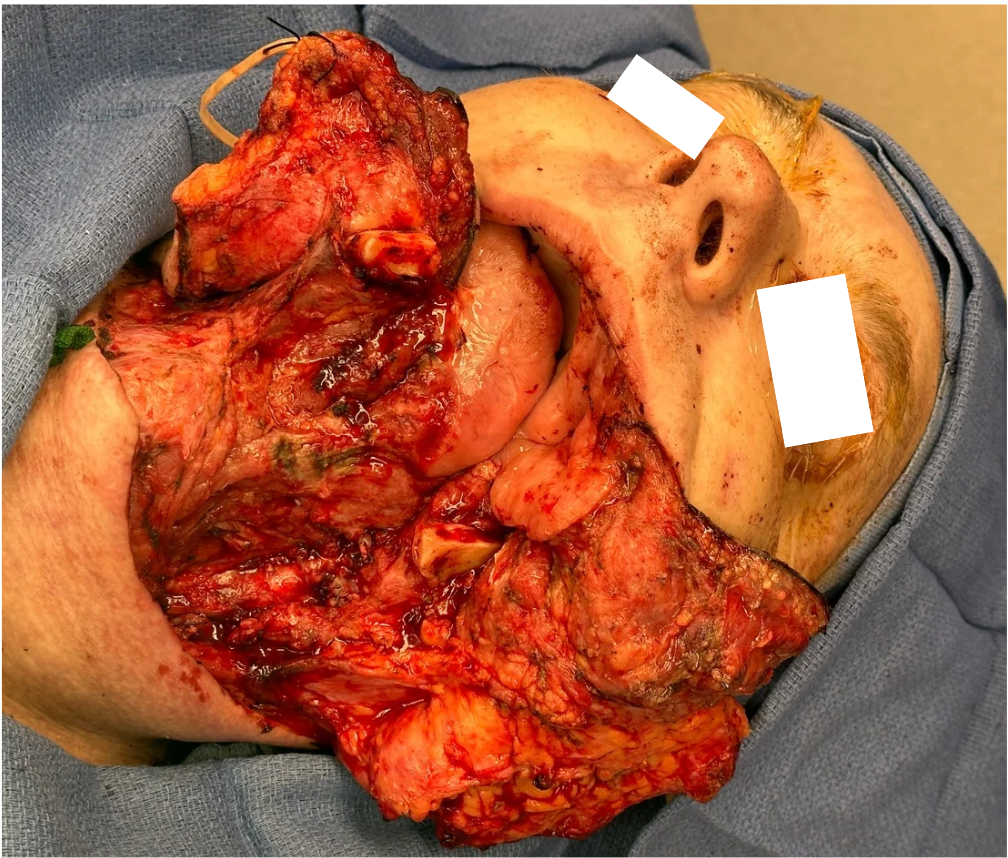

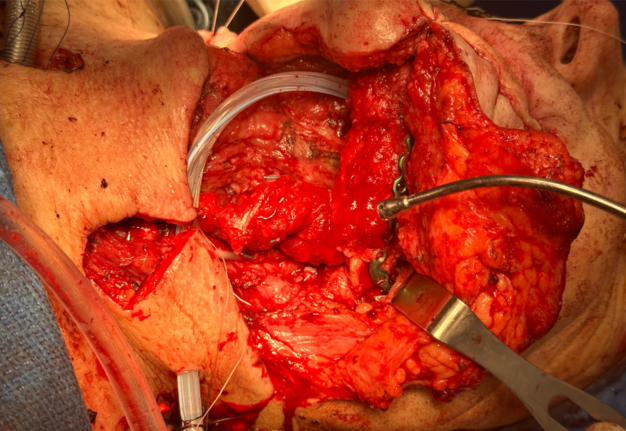

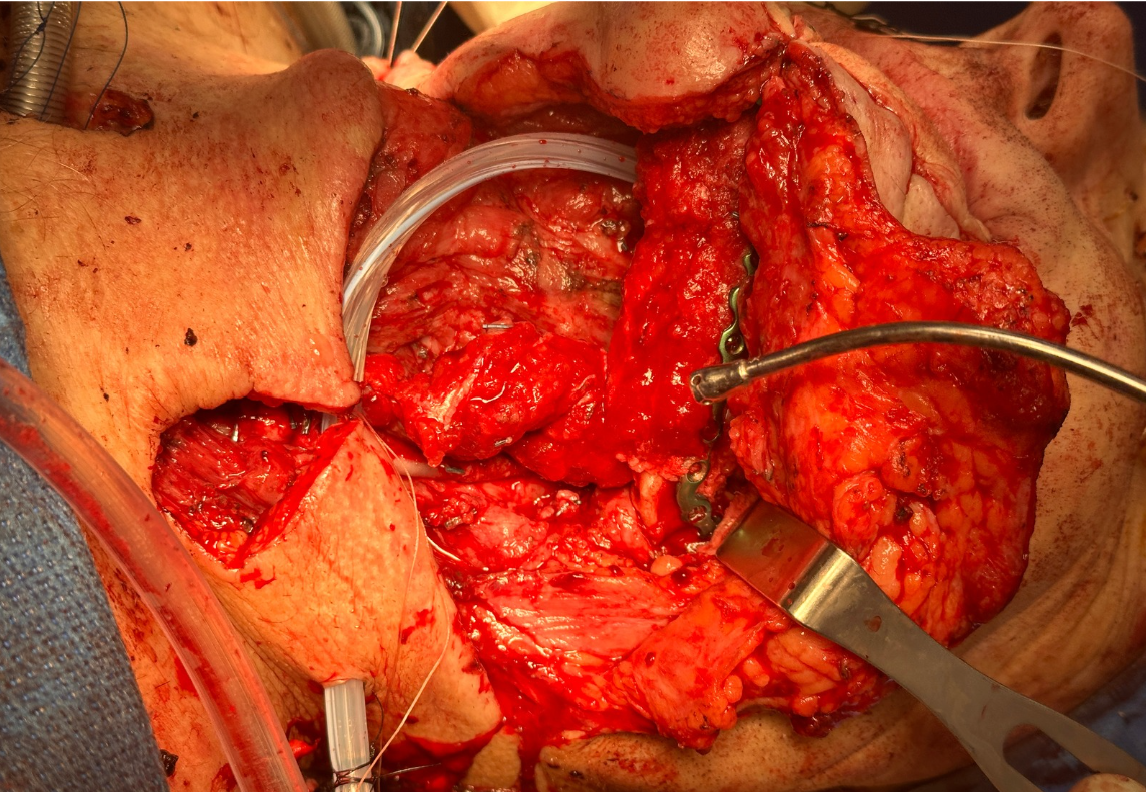

Representative intraoperative and postoperative photographs are provided in Figures 1–4, illustrating the explanted flap, the revised recipient site, revision flap inset, and final closure. The second flap remained viable throughout the postoperative period, with strong Doppler signals and no clinical signs of compromise. The patient tolerated the anticoagulation regimen well and was discharged home on postoperative day twelve without complications.

FIGURE 3. Inset of revision osteocutaneous fibula free flap. Intraoperative photograph showing the revision osteocutaneous fibula free flap after inset into the mandibular defect. The fibular bone segment is secured in position with fixation hardware, while the skin paddle and soft tissue components are oriented for reconstruction of the composite defect.

FIGURE 4. Immediate postoperative result following revision osteocutaneous fibula free flap reconstruction. Clinical photograph demonstrating the patient immediately after skin closure. The osteocutaneous fibula free flap skin paddle is clearly visible, inset into the facial defect, with the incision lines closed primarily.

The patient passed away during the follow-up period from causes unrelated to the surgery or its immediate complications. As a result, a direct patient perspective could not be obtained. The authors acknowledge the importance of including patient-reported experiences in case reporting and regret this limitation.

Discussion

This case represents a rare occurrence of intraoperative and postoperative arterial and venous thromboses during fibula free flap reconstruction of the mandible in a patient with previously undiagnosed heterozygous FVL. While FVL is primarily associated with venous thrombotic events, the manifestation of concomitant arterial thrombosis in microsurgical reconstruction is uncommon and poses significant diagnostic and management challenges [16, 18-21]. Most large studies have not shown a significantly increased risk of arterial thrombosis in FVL-positive patients [10, 24-26], although mixed reports exist in the literature [16, 29], making this dual presentation particularly noteworthy and underscoring the need for heightened clinical suspicion and adaptive perioperative planning.

FVL is a well-established risk factor for perioperative venous thromboembolism and has been linked to increased rates of free flap thrombosis and failure, with poor salvage outcomes frequently reported despite prompt intervention [16, 18, 24-28]. Faber et al. (2011) conducted a retrospective review of microvascular reconstructions complicated by unexplained thrombosis and found that flap failure was often the first sign of an underlying thrombophilia such as FVL, with salvage attempts proving unsuccessful [29]. Based on these findings, they advocated for targeted thrombophilia screening in patients with unexplained or recurrent thrombosis and proposed an aggressive, individualized anticoagulation protocol: preoperative LMWH, intraoperative continuous intravenous UFH with aPTT monitoring, and postoperative continuation of anticoagulation until discharge. Case reports such as that by Lugo et al. (2017) provide additional insights, demonstrating that successful free tissue transfer can be achieved in patients with inherited thrombophilia through coordinated multidisciplinary planning and a tailored anticoagulation regimen [30]. In their case, a patient with a strong personal and family history of VTE who was heterozygous for FVL underwent osteocutaneous scapular free flap reconstruction without complications, utilizing intraoperative heparin followed by postoperative aspirin and LMWH. The experiences of Faber et al. and Lugo et al. suggest that individualized perioperative care is essential, and that a range of anticoagulation strategies can be safely and effectively employed in patients with FVL.

In a retrospective study, Wang et al. (2017) evaluated 41 hypercoagulable patients undergoing free flap reconstruction, including those with FVL and several other thrombophilias, and observed notably high rates of flap thrombosis (20.7%) and flap loss (15.5%) [20]. Many of these patients had a history of thrombotic events before the age of 50, an important clinical clue that should raise suspicion for an underlying thrombophilia and prompt further evaluation. Importantly, in this cohort, no postoperative thrombosed flaps were successfully salvaged, despite aggressive management, and most thromboses occurred in the delayed postoperative period. These findings suggest that while free tissue transfer can be feasible in patients with thrombophilia, the risk of thrombotic complications and failed salvage is significantly increased. Clinicians should be vigilant in identifying patients at risk, seek multidisciplinary perioperative planning, and ensure close postoperative monitoring.

Therapeutic anticoagulation may not be a simple or definitive solution for free flap patients with thrombophilia. Nguyen et al. (2019) retrospectively analyzed 28 free flaps in 24 patients with diagnosed thrombophilias [31]. Although they achieved 100% flap survival, 43% of patients experienced complications, including flap thrombosis, hematoma, pulmonary embolism, or deep vein thrombosis. They found that therapeutic heparin infusion was associated with an increased risk of hematoma. This observation is supported by Dawoud et al. (2021), whose meta-analysis of over 3,500 free flaps found that therapeutic-dose anticoagulation did not significantly reduce the rates of thrombosis or flap loss, but did significantly increase the risk of hematoma and bleeding complications [32].

The exact mechanism underlying the increased risk of hematoma and bleeding complications with therapeutic heparin anticoagulation in these patients remains unclear, though several factors may play a role. These patients have a persistent prothrombotic tendency that can overwhelm the effects of standard heparin dosing, particularly if anticoagulation is subtherapeutic or interrupted [17, 31-32]. Surgical trauma further amplifies this risk by promoting endothelial injury and hypofibrinolysis [17]. While heparin is known to enhance antithrombin III activity to inhibit thrombin and factor Xa, it does not effectively suppress platelet activation or aggregation, processes that are particularly important in microvascular thrombosis [17]. Platelet-driven clot formation can occur independently of the pathways targeted by heparin, meaning that microthrombi at the anastomosis site may still develop even in the presence of systemic anticoagulation. Moreover, heparin has been shown in some contexts to paradoxically activate platelets, particularly at certain dosages or in susceptible individuals, further promoting platelet-rich thrombus formation [17]. Thus, therapeutic heparinization may not fully protect against microvascular thrombosis and may contribute to persistent hematologic complications in patients with FVL undergoing free tissue transfer.

It can be argued that routine preoperative thrombophilia screening in head and neck microvascular surgery may enable more individualized anticoagulation and potentially reduce the risk of perioperative thrombotic complications and flap loss. Such screening may also help guide long-term risk counseling for patients and their families. However, we support current guidelines from the American Society of Hematology and the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Society, which recommend selective, risk-based testing [31-33]. Our experience, including the presented case, suggests that current guideline recommendations for selective thrombophilia screening are reasonable when paired with a thorough clinical history. Careful assessment often suffices to identify patients at increased risk and guide management. Still, we acknowledge that even detailed histories may fail to uncover occult hypercoagulable states, leaving a subset of at-risk individuals unidentified. In this case, targeted evaluation and close collaboration with hematology enabled successful outcomes without unnecessary testing or overtreatment, further supporting the clinical validity of a selective approach. However, the limitations of history-based risk stratification highlight the need for further research and development of improved screening tools to better identify and manage high-risk patients in this population.

It is important to note that while previous radiotherapy can increase technical complexity of microvascular surgery due to vessel fibrosis or friability [34-37], there is no strong evidence that it directly predisposes to flap thrombosis [38-40]. As such, prior radiation for laryngeal cancer was unlikely to have significantly contributed to flap failure in this patient. The decision to use the chosen recipient vessels was based on accessibility and vessel quality, rather than any limitation imposed by prior radiotherapy. ERAS principles were followed as closely as the clinical context permitted, making it unlikely that deviation from standard perioperative protocol contributed to the flap failure [41-42].

Early consideration of thrombophilia should be part of the diagnostic workup for unexplained flap thrombosis, as individualized, multidisciplinary management can optimize outcomes even after initial failure. Based on our experience and current literature, we believe that in cases where an initial free flap fails without an identifiable technical or systemic cause, a thrombophilia workup should be strongly considered. If testing cannot be completed in time, but clinical suspicion of an occult hypercoagulable state remains high, we recommend bolusing with 5,000 units of intravenous UFH prior to revision microvascular surgery. If intraoperative clotting is encountered, additional bolusing of UFH should be considered to achieve a supratherapeutic aPTT. This should be followed by postoperative maintenance of a therapeutic aPTT target of 100 seconds or more in the intensive care setting. This strategy may provide a practical and adaptable pathway for optimizing outcomes in patients with suspected but unconfirmed thrombophilia.

The generalizability of this case is limited by its single-patient nature, and most available literature consists of retrospective series and case reports, both prone to selection and publication bias. Clinical investigation for thrombophilia in microvascular failure remains uncommon, likely resulting in underdiagnosis and hindering the development of universal, evidence-based guidelines. To advance the field, prospective studies are needed to clarify optimal screening, perioperative management, and standards of care for these complex patients, but this is difficult given the low prevalence of these coagulopathies.

Conclusion

This case highlights the challenges of microvascular reconstruction in patients with unrecognized hypercoagulable disorders. Early flap failure due to occult heterozygous factor V Leiden was successfully managed through targeted diagnosis and tailored anticoagulation, resulting in a favorable outcome. In the continued absence of standardized protocols for thrombophilia management in head and neck microsurgery, our experience underscores the importance of individualized risk assessment, early involvement of hematology, and adaptable perioperative strategies. Based on our clinical experience, we recommend that in cases of unexplained flap thrombosis with high suspicion of an underlying coagulopathy, especially when thrombophilia workup cannot be completed expeditiously, surgeons consider a proactive anticoagulation strategy. This includes administering intravenous UFH prior to microvascular anastomosis. If clotting is observed intraoperatively, additional UFH boluses may be used with a minimum target aPTT of 100 seconds maintained postoperatively. Careful evaluation of unexplained flap thrombosis for potential underlying coagulopathies may contribute to improved reconstructive outcomes and should be integrated into the management of similarly complex cases.

Funding

No funding, grants, or other support was received for conducting this study or preparing this manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

No funding, grants, or other support was received for conducting this study or preparing this manuscript.

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

The authors have no financial or proprietary interests in any material discussed in this article.

Author Contributions

Bryce Thornton, BS: Drafted the manuscript, performed literature review, data collection and figure preparation, and coordinated manuscript revisions.

Noah Rothman, BS: Assisted with data collection, literature review, and manuscript drafting and revision.

Kirav Patel, MD: Provided clinical expertise and reviewed the manuscript for important content.

Michael Kase, DMD: Contributed to patient care, clinical documentation, and critical revision of the manuscript.

Anthony B. Morlandt, DDS, MD: Served as the ablative surgeon, contributed to patient management and surgical details, and provided critical review and revisions of the manuscript.

Jay Ponto, DDS, MD: Supervised the project and provided mentorship, served as microvascular reconstructive surgeon, and critically revised the manuscript for final approval.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics Approval

The study was determined to be exempt from IRB review and does not require formal ethics approval.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable; the patient is deceased.

Consent to Publish

Not applicable; the patient is deceased.

References (42)

-

Kucur C, Durmus K, Uysal IO, et al. Management of complications and compromised free flaps following major head and neck surgery. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273(1):209-213. doi:10.1007/s00405-014-3489-1

-

Katna R, Naik G, Girkar F, et al. Clinical outcomes for microvascular reconstruction in oral cancers: experience from a single surgical centre. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2023;105(3):247-251. doi:10.1308/rcsann.2021.0295

-

Poisson M, Longis J, Schlund M, et al. Postoperative morbidity of free flaps in head and neck cancer reconstruction: a report regarding 215 cases. Clin Oral Investig. 2019;23(5):2165-2171. doi:10.1007/s00784-018-2653-1

-

Slijepcevic AA, Young G, Shinn J, et al. Success and outcomes following a second salvage attempt for free flap compromise in patients undergoing head and neck reconstruction. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;148(6):555-560. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2022.0793

-

Chiu YH, Chang DH, Perng CK. Vascular complications and free flap salvage in head and neck reconstructive surgery: analysis of 150 cases of reexploration. Ann Plast Surg. 2017;78(3 Suppl 2):S83-S88. doi:10.1097/SAP.0000000000001011

-

Walia A, Lee JJ, Jackson RS, et al. Management of flap failure after head and neck reconstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;167(2):224-235. doi:10.1177/01945998211044683

-

Stevens MN, Freeman MH, Shinn JR, et al. Preoperative predictors of free flap failure. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023;168(2):180-187. doi:10.1177/01945998221091908

-

Davison SP, Kessler CM, Al-Attar A. Microvascular free flap failure caused by unrecognized hypercoagulability. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(2):490-495. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181adcf35

-

Senchenkov A, Lemaine V, Tran NV. Management of perioperative microvascular thrombotic complications - the use of multiagent anticoagulation algorithm in 395 consecutive free flaps. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2015;68(9):1293-1303. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2015.05.011

-

Kujovich JL. Factor V Leiden thrombophilia. Genet Med. 2011;13(1):1-16. doi:10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181faa0f2

-

Aparicio C, Dahlbäck B. Molecular mechanisms of activated protein C resistance. Properties of factor V isolated from an individual with homozygosity for the Arg506 to GLN mutation in the factor V gene. Biochem J. 1996;313(Pt 2):467-472. doi:10.1042/bj3130467

-

Bauer KA. Long-term management of venous thromboembolism: a 61-year-old woman with unprovoked venous thromboembolism. JAMA. 2011;305(13):1336-1345. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.361

-

Kahn SR, Lim W, Dunn AS, et al. Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e195S-e226S. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2296

-

Middeldorp S, Nieuwlaat R, Baumann Kreuziger L, et al. American Society of Hematology 2023 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: thrombophilia testing. Blood Adv. 2023;7(22):7101-7138. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2023010177

-

Deldar R, Gupta N, Bovill JD, et al. Risk-stratified anticoagulation protocol increases success of lower extremity free tissue transfer in the setting of thrombophilia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2023;152(3):653-666. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000010293

-

Khansa I, Colakoglu S, Tomich DC, Nguyen MD, Lee BT. Factor V Leiden associated with flap loss in microsurgical breast reconstruction. Microsurgery. 2011;31(5):409-412. doi:10.1002/micr.20879

-

Nelson JA, Chung CU, Bauder AR, Wu LC. Prevention of thrombosis in hypercoagulable patients undergoing microsurgery: a novel anticoagulation protocol. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2017;70(3):307-312. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2016.12.001

-

Au E, Shao I, Elias Z, Koivu A, Zabida A, Shih AW, Cserti-Gazdewich C, van Klei WA, Bartoszko J. Complications of Factor V Leiden in Adults Undergoing Noncardiac Surgical Procedures: A Systematic Review. Anesth Analg. 2023 Sep 1;137(3):601-617. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000006483. Epub 2023 Aug 17. PMID: 37053508.

-

Chopard R, Albertsen IE, Piazza G. Diagnosis and Treatment of Lower Extremity Venous Thromboembolism: A Review. JAMA. 2020;324(17):1765–1776. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.17272

-

Wang TY, Serletti JM, Cuker A, McGrath J, Low DW, Kovach SJ, Wu LC. Free tissue transfer in the hypercoagulable patient: a review of 58 flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012 Feb;129(2):443-453. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31823aec4d. PMID: 21987047.

-

Liu FC, Miller TJ, Wan DC, Momeni A. The Impact of Coagulopathy on Clinical Outcomes following Microsurgical Breast Reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021 Jul 1;148(1):14e-18e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000008099. PMID: 34003808.

-

Pannucci CJ, Kovach SJ, Cuker A. Microsurgery and the Hypercoagulable State: A Hematologist's Perspective. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015 Oct;136(4):545e-552e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000001591. PMID: 26397274.

-

Speck NE, Hellstern P, Farhadi J. Microsurgical Breast Reconstruction in Patients with Disorders of Hemostasis: Perioperative Risks and Management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2022 Oct 1;150(4 Suppl ):95S-104S. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000009499. Epub 2022 Sep 28. PMID: 35943960; PMCID: PMC10262037.

-

Price DT, Ridker PM. Factor V Leiden mutation and the risks for thromboembolic disease: a clinical perspective. Ann Intern Med. 1997 Nov 15;127(10):895-903. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-10-199711150-00007. PMID: 9382368.

-

Donahue BS. Factor V Leiden and perioperative risk. Anesth Analg. 2004 Jun;98(6):1623-1634. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000113545.03192.FD. PMID: 15155315.

-

De Stefano V, Chiusolo P, Paciaroni K, Leone G. Epidemiology of factor V Leiden: clinical implications. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1998;24(4):367-79. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-996025. PMID: 9763354.

-

Factor V Leiden thrombophilia [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US), Genetics Home Reference; [updated 2024 May 15]. Available from: https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/factor-v-leiden-thrombophilia/ [cited 2025 Jul 19].

-

Zarb RM, Lamberton C, Ramamurthi A, Berry V, Adamson KA, Doren EL, Hettinger PC, Hijjawi JB, LoGiudice JA. Microsurgical breast reconstruction and primary hypercoagulable disorders. Microsurgery. 2024 Feb;44(2):e31146. doi: 10.1002/micr.31146. PMID: 38342998.

-

Faber J, Schuster F, Hartmann S, Brands RC, Fuchs A, Straub A, Fischer M, Müller-Richter U, Linz C. Successful microvascular surgery in patients with thrombophilia in head and neck surgery: a case series. J Med Case Rep. 2024 Feb 28;18(1):119. doi: 10.1186/s13256-024-04403-8. PMID: 38414080; PMCID: PMC10900673.

-

Lugo R, Alotaibi F, Shirley B, Kim DD, Covello P, Patel S. Head and neck free tissue transfer in a patient with factor V Leiden: case report and review of the literature. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2021 Dec;25(4):571-574. doi: 10.1007/s10006-021-00939-x. Epub 2021 Jan 20. PMID: 33471220.

-

Nguyen TT, Egan KG, Crowe DL, Nazir N, Przylecki WH, Andrews BT. Outcomes of Head and Neck Microvascular Reconstruction in Hypercoagulable Patients. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2020 May;36(4):271-275. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-3401846. Epub 2019 Dec 13. PMID: 31858490.

-

Dawoud BES, Kent S, Tabbenor O, Markose G, Java K, Kyzas P. Does anticoagulation improve outcomes of microvascular free flap reconstruction following head and neck surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2022 Dec;60(10):1292-1302. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2022.07.016. Epub 2022 Sep 16. PMID: 36328862.

-

Connors JM. Thrombophilia Testing and Venous Thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2017 Sep 21;377(12):1177-1187. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1700365. PMID: 28930509.

-

Kameni LE, Januszyk M, Berry CE, Downer MA Jr, Parker JB, Morgan AG, Valencia C, Griffin M, Li DJ, Liang NE, Momeni A, Longaker MT, Wan DC. A Review of Radiation-Induced Vascular Injury and Clinical Impact. Ann Plast Surg. 2024 Feb 1;92(2):181-185. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000003723. Epub 2023 Oct 21. PMID: 37962260.

-

Valentino J, Weinstein L, Rosenblum R, Regine W, Weinstein M. Radiation and Intra-arterial Cisplatin: Effects on Arteries and Free Tissue Transfer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;126(2):215–219. doi:10.1001/archotol.126.2.215.

-

Lee S, Thiele C. Factors associated with free flap complications after head and neck reconstruction and the molecular basis of fibrotic tissue rearrangement in preirradiated soft tissue. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010 Sep;68(9):2169-78. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.08.026. PMID: 20605307.

-

Thankappan K. Microvascular free tissue transfer after prior radiotherapy in head and neck reconstruction - a review. Surg Oncol. 2010 Dec;19(4):227-34. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2009.06.001. Epub 2009 Jun 30. PMID: 19570672.

-

Schuderer JG, Dinh HT, Spoerl S, Taxis J, Fiedler M, Gottsauner JM, Maurer M, Reichert TE, Meier JK, Weber F, Ettl T. Risk Factors for Flap Loss: Analysis of Donor and Recipient Vessel Morphology in Patients Undergoing Microvascular Head and Neck Reconstructions. J Clin Med. 2023 Aug 10;12(16):5206. doi: 10.3390/jcm12165206. Erratum in: J Clin Med. 2024 Jan 18;13(2):548. doi: 10.3390/jcm13020548. PMID: 37629249; PMCID: PMC10455344.

-

Fracol ME, Basta MN, Nelson JA, Fischer JP, Wu LC, Serletti JM, Fosnot J. Bilateral Free Flap Breast Reconstruction After Unilateral Radiation: Comparing Intraoperative Vascular Complications and Postoperative Outcomes in Radiated Versus Nonradiated Breasts. Ann Plast Surg. 2016 Mar;76(3):311-4. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000000545. PMID: 26545214.

-

Mijiti A, Kuerbantayi N, Zhang ZQ, Su MY, Zhang XH, Huojia M. Influence of preoperative radiotherapy on head and neck free-flap reconstruction: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Neck. 2020 Aug;42(8):2165-2180. doi: 10.1002/hed.26136. Epub 2020 Mar 4. PMID: 32129547.

-

Dort JC, Farwell DG, Findlay M, et al. Optimal Perioperative Care in Major Head and Neck Cancer Surgery With Free Flap Reconstruction: A Consensus Review and Recommendations From the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Society. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;143(3):292–303. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2016.2981

-

Chorath K, Go B, Shinn JR, Mady LJ, Poonia S, Newman J, Cannady S, Revenaugh PC, Moreira A, Rajasekaran K. Enhanced recovery after surgery for head and neck free flap reconstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Oncol. 2021 Feb;113:105117. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2020.105117. Epub 2020 Dec 23. PMID: 33360446.