Correlation and Accuracy of Labial Minor Salivary Gland Biopsy in the Establishment of Diagnosis in Patients with Suspected Sjögren’s Syndrome

September 30, 2018

https://doi.org/10.23999/j.dtomp.2018.3.5

J Diagn Treat Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2018;2:122–31.

Under a Creative Commons license

HOW TO CITE THIS ARTICLE

Kilipiris EG, Machalekova K, Fountoulaki G, Andrade K, Mantziaris N, Stanko P. Correlation and accuracy of labial minor salivary gland biopsy in the establishment of diagnosis in patients with suspected Sjögren’s syndrome. J Diagn Treat Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2018;2(3):122−31.

Contents: Abstract | Introduction | Materials and methods | Results | Discussion | Conclusion | References (13)

Abstract

Purpose: The goal of this paper is to find out the correlation, and evaluate the accuracy of labial minor salivary gland biopsy as a diagnostic tool in the multidisciplinary management of patients with Sjögren’s syndrome.

Patients and Methods: Thirty seven patients referred to our outpatient office between January 2016 and December 2017 from a rheumatologist for biopsy examination, as part of the complex diagnostic plan for suspected Sjögren syndrome were included in the current study. Each specimen was examined histomorphometrically by the pathologist to calculate the focus score describing the degree of salivary gland inflammatory infiltration.

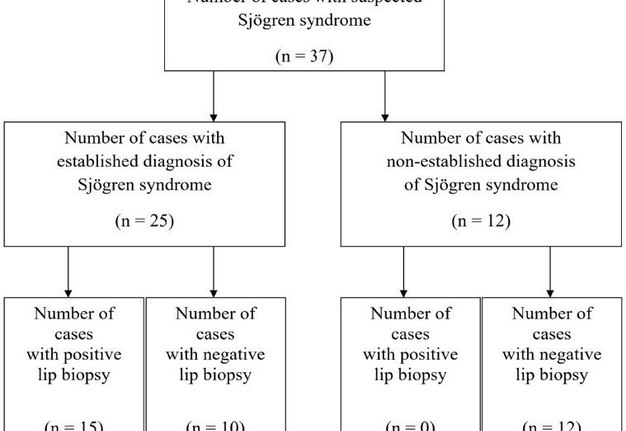

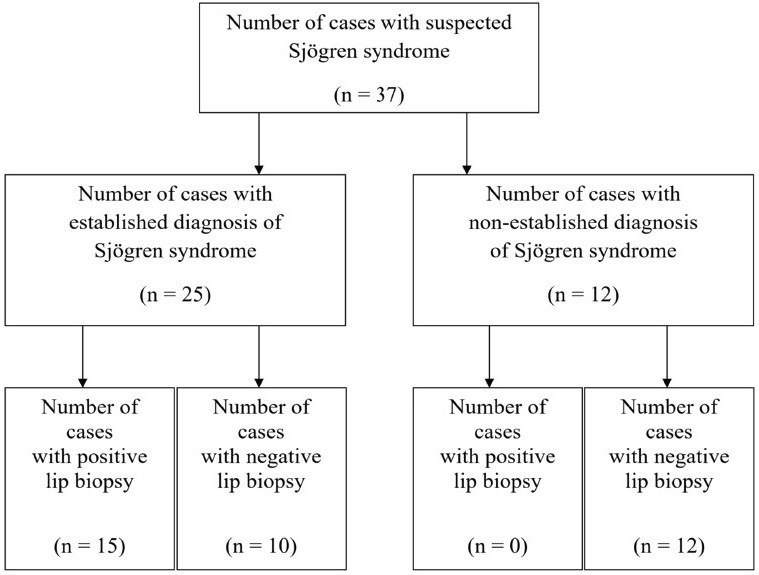

Results: From the total number of patients, 25 presented with an established Sjögren syndrome diagnosis by fulfilling the revised American-European criteria. From those 15 had a positive lip biopsy. The rest 10 patients from the total group who were diagnosed with Sjögren syndrome based on the same criteria had a negative lip biopsy.

Conclusion: The labial minor salivary gland biopsy is a valuable diagnostic tool to establish the diagnosis of Sjögren syndrome. However, a positive biopsy result must always be correlated with all the other diagnostic criteria to prove the exact diagnosis.

Introduction

Sjögren syndrome is a systemic, slowly progressive, chronic inflammatory autoimmune disease characterized by chronic lymphocytic invasion and eventual destruction of exocrine glandular structures, specifically the salivary and lacrimal glands. Is one of the most prevalent autoimmune disorders [1].

Classically, two types have been described: i) the primary Sjögren syndrome characterized by a combination of keratoconjunctivitis sicca and xerostomia and ii) the secondary Sjögren syndrome which is defined by a triad of keratoconjunctivitis sicca, xerostomia and an autoimmune disease, usually rheumatoid arthritis, but also systemic lupus erythematosus or scleroderma.

Nine out of ten Sjögren syndrome patients are women, around the fifth decade of life [2]. The spectrum of the disease extends from an organ-specific autoimmune disease to a systemic process with diverse extraglandular manifestations. The hallmark symptoms of Sjögren syndrome are dry mouth and dry eyes. However, clinical features may also include other head and neck manifestations involving the nose, ears, throat, thyroid gland, and systemic symptoms such as neurologic, pulmonary, gastrointestinal and hematologic [3].

Sjögren syndrome often is undiagnosed or misdiagnosed. The symptoms of Sjögren syndrome may mimic those of menopause, drug side effects, or medical conditions such as lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome and multiple sclerosis. Because all symptoms are not always present at the same time and because Sjögren syndrome can involve several body systems, physicians sometimes treat each symptom individually and do not recognize that a systemic disease is present [4]. Eight to ten years are generally required for the disorder to progress from initial symptoms to the development of the syndrome. While some patients experience mild discomfort, others suffer debilitating symptoms that greatly impair their functioning.

Sjögren syndrome is treatable. Early diagnosis and consequently proper treatment may prevent serious complications and greatly improve the quality of life for these patients [5]. However, patients with Sjögren syndrome are generally picked up at a late stage in their disease, after the salivary and lacrimal glands are already destroyed, because they are asymptomatic until that time. Unfortunately, at this point only symptomatic treatment can be offered.

Although rheumatologists have primary responsibility for managing Sjögren syndrome, patients suspected to have Sjögren syndrome often are referred to an Oral and Maxillofacial surgeon for evaluation and biopsy to rule out the disease.

A Sjögren syndrome work-up can include various objective tests, such as Schirmer test, sialometry, injection sialography and scintigraphy that add little to the diagnosis, but provide information about the degree of ductal and acinar destruction [6]. The same information can be obtained from a CT or MRI scan, which will often show internal hypodense areas indicative of ductal ectasia and salivary pooling.

A more focused work-up should seek to establish histopathological confirmation. For this purpose, oral labial minor salivary gland biopsy has been traditionally considered the most valuable diagnostic tool for the diagnosis of Sjögren syndrome, especially in patients who present with inconclusive clinical findings [7]. With all this background, the aim of this study is to discover the accuracy and effectiveness of this diagnostic procedure in the establishment of diagnosis in patients with suspected Sjögren syndrome.

Materials and methods

Between January 2016 and December 2017, 37 patients were referred to the Outpatients Office of the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, St. Elizabeth Oncologic Clinic and Comenius University in Bratislava, Slovakia with suspected Sjögren syndrome.

Criteria for patient selection to this study were: i) patients sent from rheumatologists for further examination of suspected Sjögren syndrome and ii) patients with at least one sicca symptom (either xerostomia or xerophthalmia) at the time of presentation. Patients with other established systemic diseases with symptoms similar to Sjögren syndrome and xerostomia as a result of medicaments, radiotherapy to the head and neck region and chemotherapy were excluded from the study.

A complete history and physical evaluation were performed. In addition to lip biopsy, the following diagnostic tools were employed: anti-SSA/Ro or anti-SSB/La antibodies, Schirmer test, ultrasonography and scintigraphy.

The biopsy specimens were taken from beneath a clinically normal mucosa of the lower lip between the midline and commissure, and 5 to 10 minor salivary glands were removed for examination. Local infiltration with anesthetic containing vasoconstrictor was applied, followed by a single incision of 1.5-2 cm vertically to just penetrate epithelium. The minor salivary glands were then removed by blunt dissection, while avoiding sensory nerves (Fig 1A, B). The fragments of minor salivary glands were sent for histopathological examination in the Department of Pathology of St. Elizabeth Oncologic Clinic and processed completely according to Sjögren syndrome focus score grading the degree of salivary gland inflammatory infiltration. A focus score of 1 or greater was considered supportive of the diagnosis of Sjögren syndrome. Long term follow up was introduced with assessment every 3 months.

Result

Of the 37 patients meeting the selection criteria, the average age at the time of presentation was 51 years. The oldest patient was 78 years and the youngest 6 years at the time of first examination. Female patients were 31 while the male patients were 6. During physical examination, patients presented with a wide range of clinical findings including xerostomia, xerophthalmia, difficulty in swallowing, inability to speak continuously for longer than several minutes, altered taste, fissured tongue, red and tender oral mucosa, decreased vision, asymmetric and painless enlargement of major salivary glands.

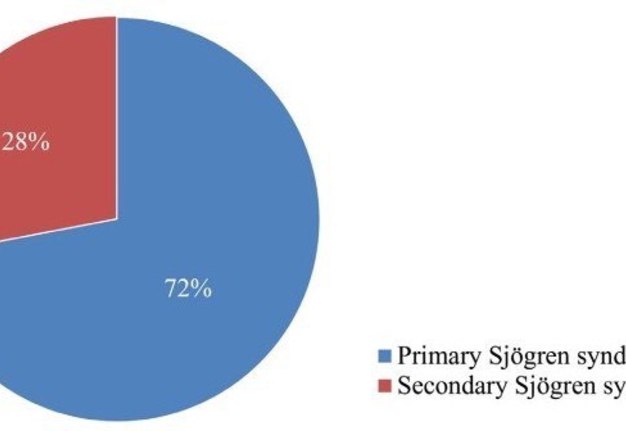

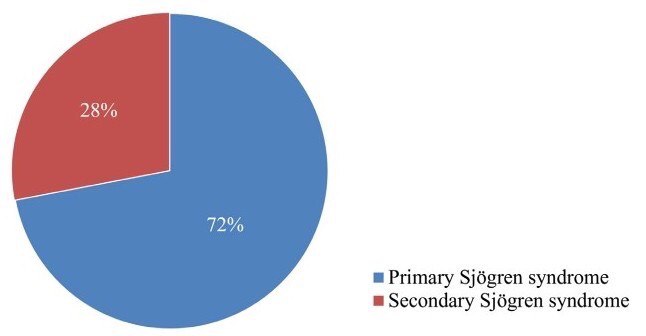

In the present study, evaluation of the accuracy of minor salivary gland lip biopsy in the support of Sjögren syndrome diagnosis was performed by comparing the biopsy result (either positive or negative) and the criteria for classification of the disease. From the 37 patients including in the study, 25 concluded with an established Sjögren syndrome diagnosis. From those, 15 (60%) had a positive lip biopsy and all of them were confirmed to fulfill the revised American―European criteria establishing the diagnosis of the syndrome. A number of 10 patients from the total group (27%) were diagnosed with Sjögren syndrome, based on the above criteria despite of presenting a negative minor salivary gland lip biopsy. All of the patients, 12 in the number, whose diagnostic criteria didn’t support the diagnosis of Sjögren syndrome, presented with a negative lip biopsy (Fig 2). Among the 25 patients diagnosed with the disease, 7 were observed with the criteria of secondary Sjögren syndrome, with the most common established connective tissue disorder being rheumatoid arthritis in 4 patients (Chart 1).

Salivary gland scintigraphy was additionally performed in 12 patients of the study group who concluded with established Sjögren syndrome. The construction of time ― activity curves presented reduced major salivary gland function. In 8 patients the radionuclide uptake from the blood to the major salivary glands was normal, but the excretion into the oral cavity was significantly decreased. The rest 4 patients who appeared with increased salivary dysfunction, both uptake and excretion of the radionuclide was diminished. Moreover, these patients presented with the highest focus score level. Characteristic histopathological changes of positive specimens included loss of acinar cells, a relative preservation of ductal structures, and the presence of an intense, focal periductal/vascular mononuclear cell infiltrate (Fig 2).

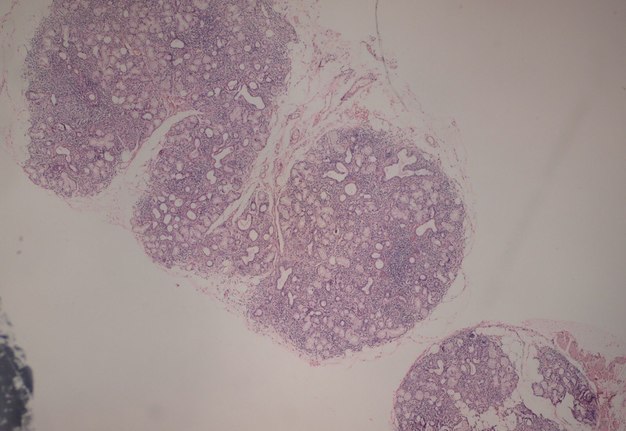

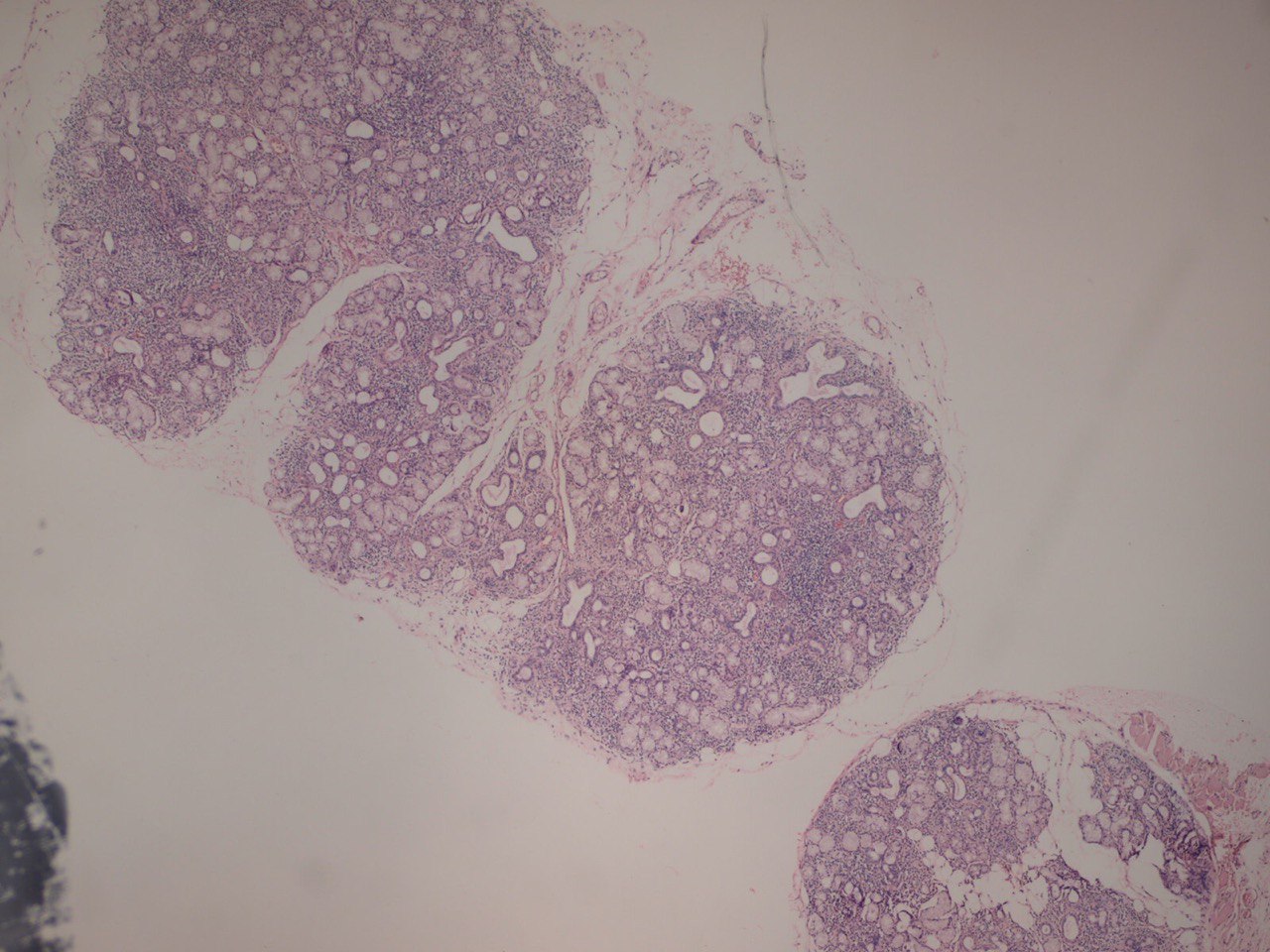

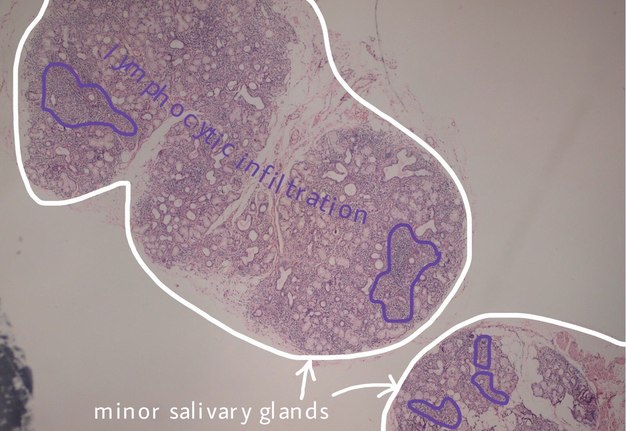

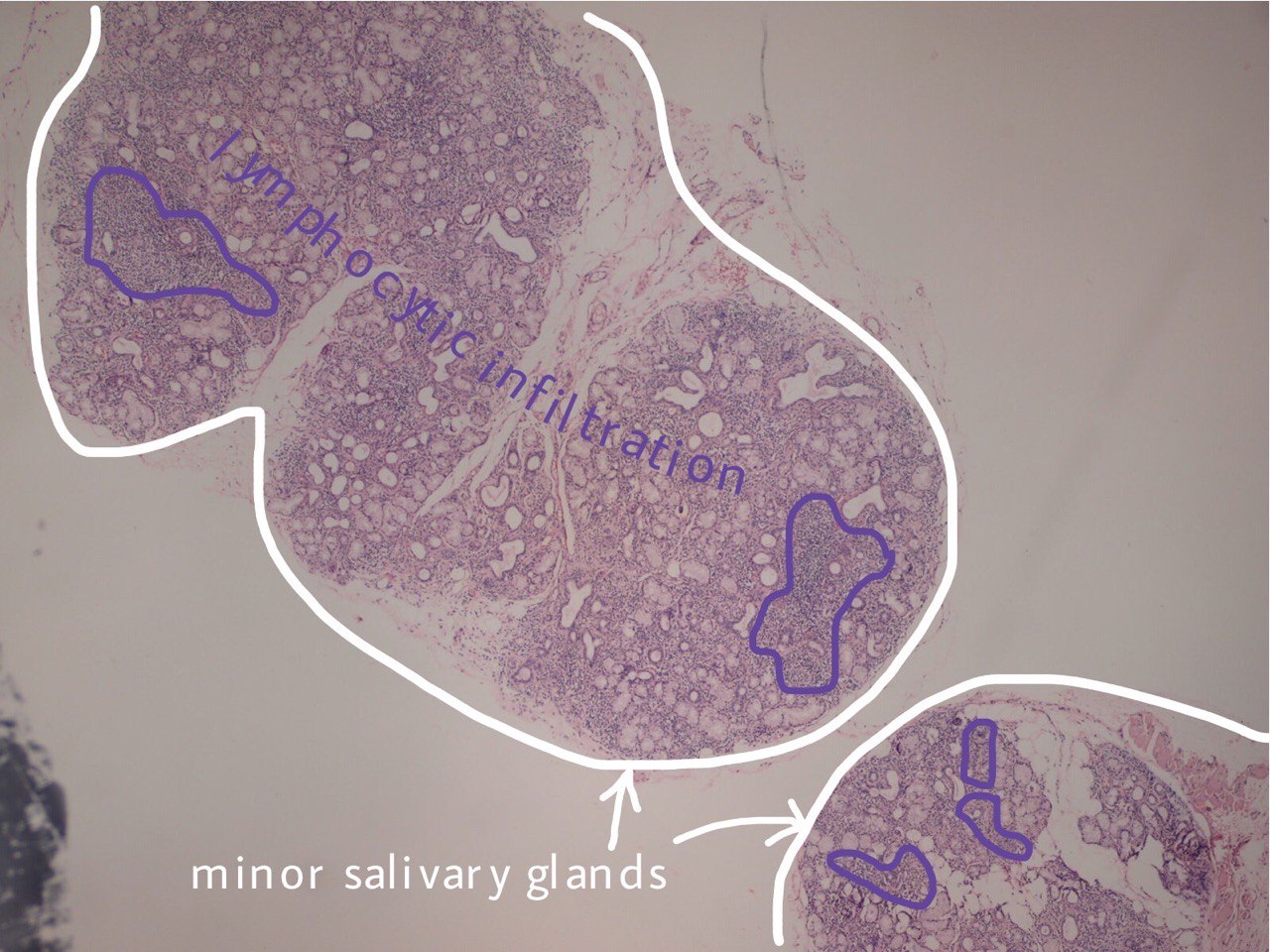

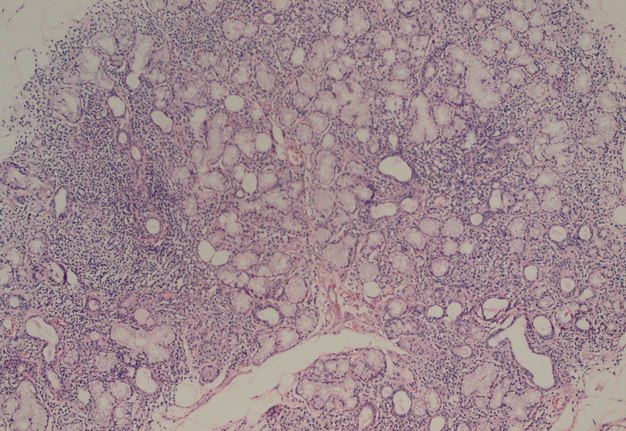

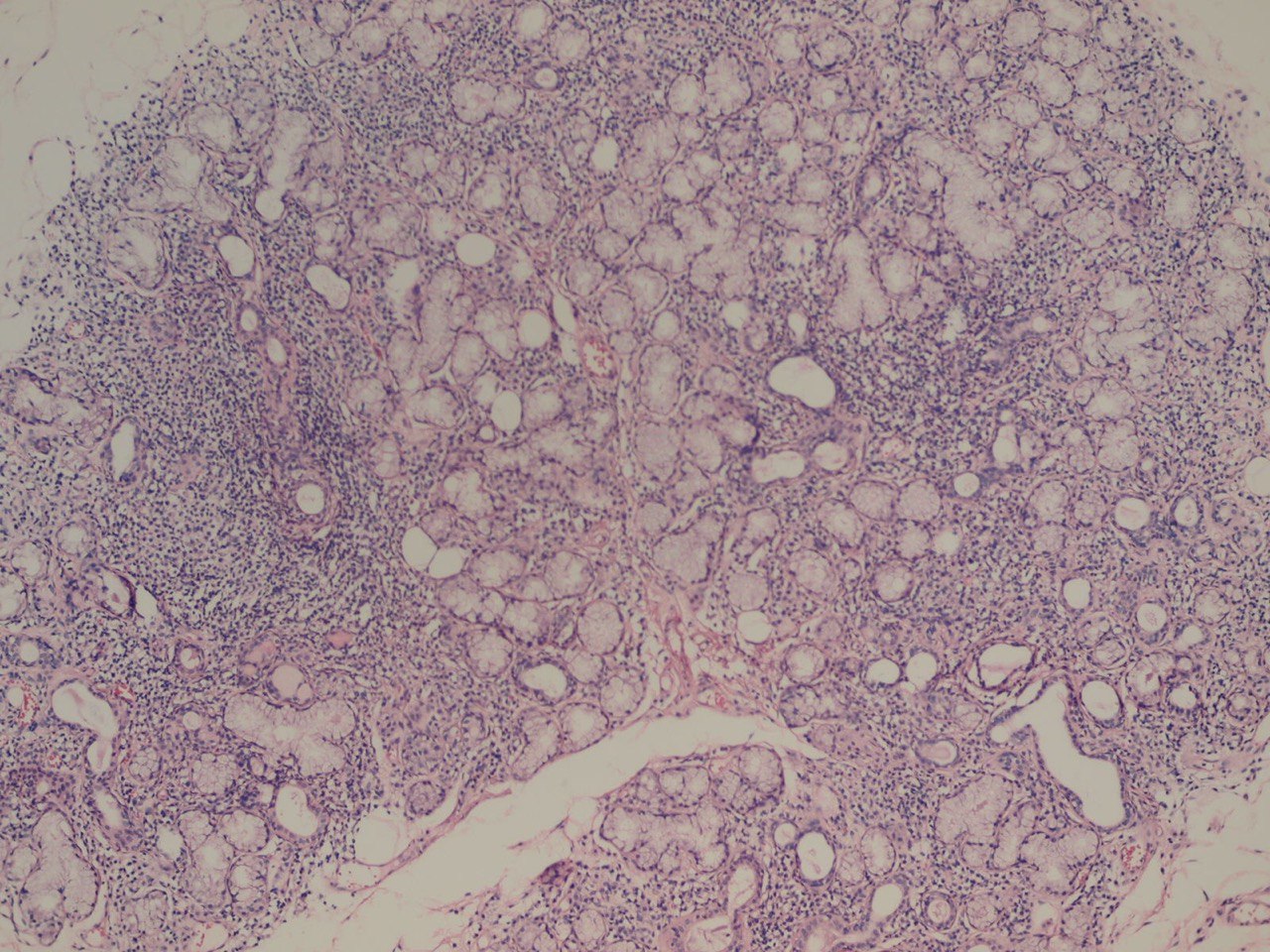

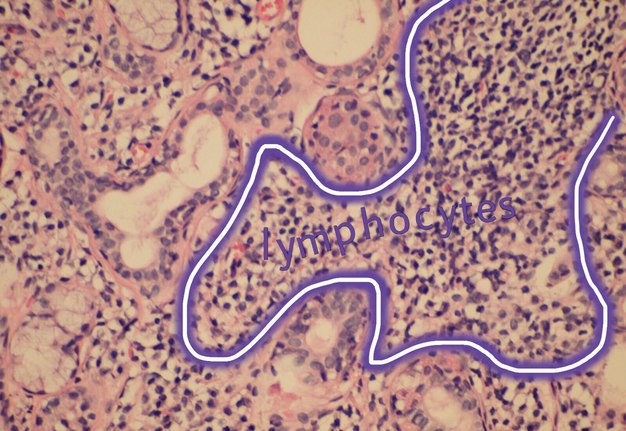

FIGURE 3A. (A) Image without notations. Two minor salivary glands exhibiting a focal lymphocytic pattern of inflammatory cell infiltration (hematoxylin and eosin stain, × 100). (B) Image with notations. Two minor salivary glands (indicated with white lines and arrows) exhibiting a focal lymphocytic pattern of inflammatory cell infiltration (the areas with biggest infiltration are indicated with purple lines and words lymphocytic infiltration).

FIGURE 3B. (A) Image without notations. Two minor salivary glands exhibiting a focal lymphocytic pattern of inflammatory cell infiltration (hematoxylin and eosin stain, × 100). (B) Image with notations. Two minor salivary glands (indicated with white lines and arrows) exhibiting a focal lymphocytic pattern of inflammatory cell infiltration (the areas with biggest infiltration are indicated with purple lines and words lymphocytic infiltration).

Discussion

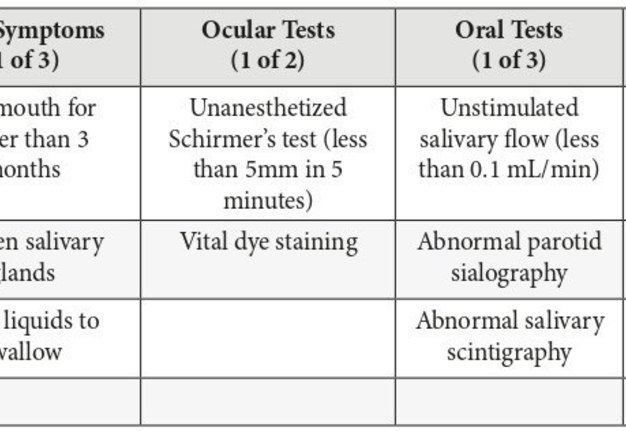

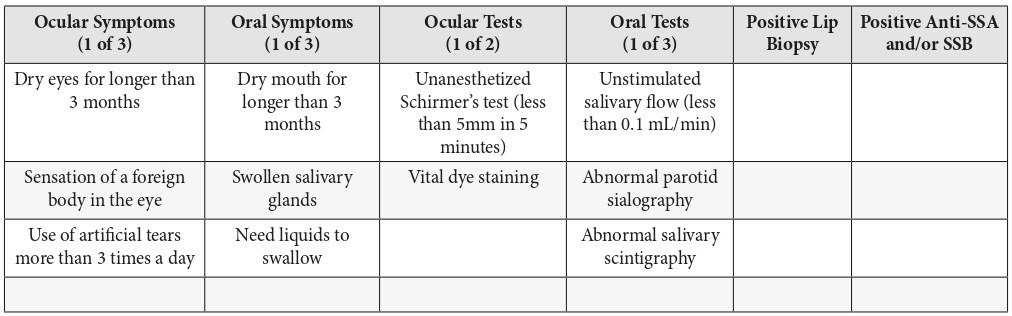

The current standards for diagnosis of Sjögren syndrome are described by the revised American-European criteria (Table 1). The diagnosis of primary Sjögren syndrome requires 4 out of the 6 criteria, involving either a positive lip biopsy or positive anti-SSA/Ro or anti-SSB/La. Secondary Sjögren syndrome requires an established connective tissue disease and at least one sicca symptom plus 2 out of 3 objective tests for either xerophthalmia or xerostomia. It should be noted that Sjögren syndrome can also be diagnosed in the absence of sicca symptoms if 3 out of 4 objective tests are positive (Table 1).

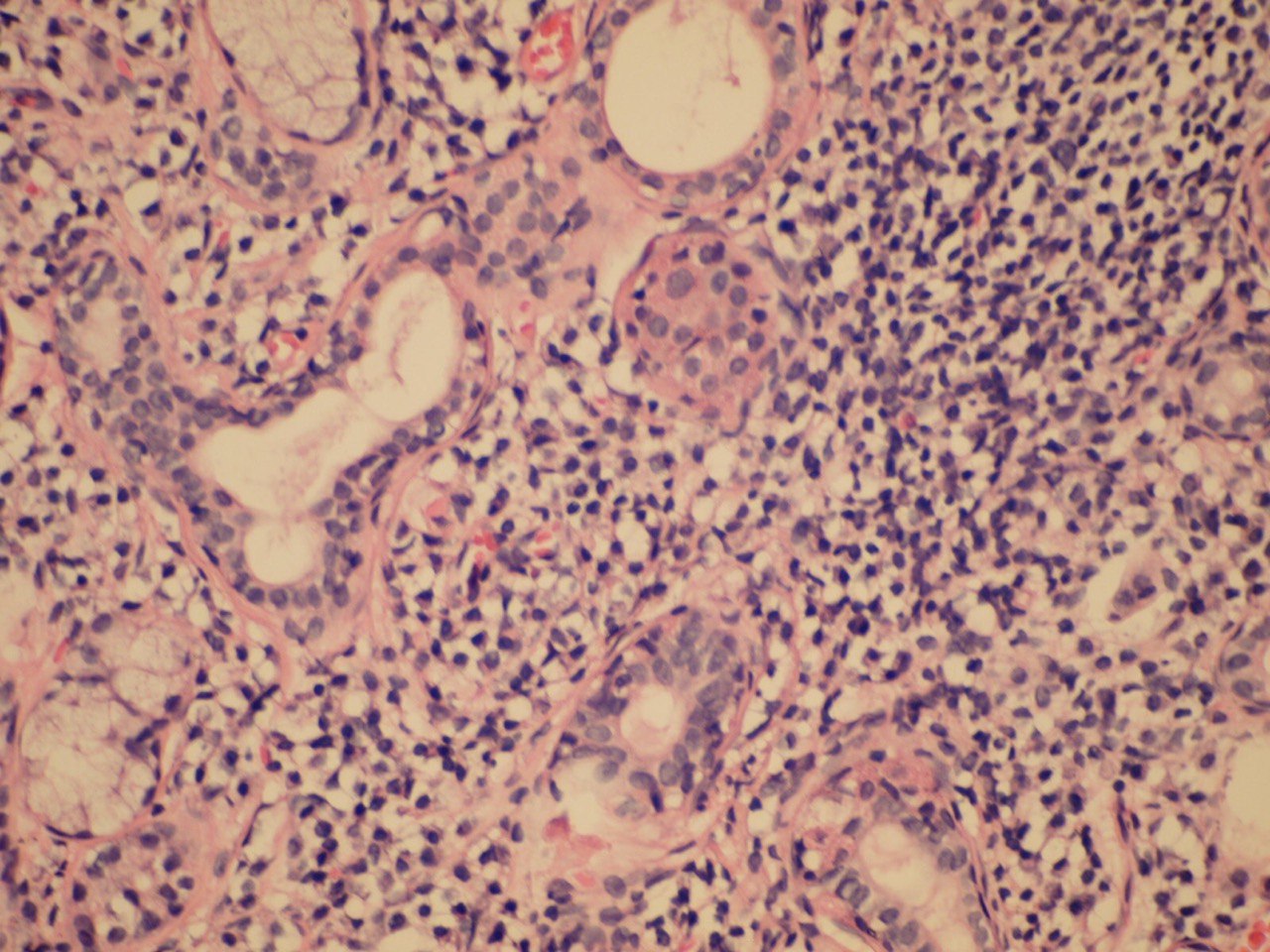

Salivary glands involved by this condition show a focal lymphocytic pattern of infiltration, in which there are multiple interstitial aggregate foci of inflammatory cells (Fig 4). An aggregate focus is defined as a collection of greater than 50 inflammatory cells. The focal lymphocytic infiltrate, including focal aggregates of 50 or more lymphocytes, defined as a focus, that are adjacent to normal appearing acini and the consistent presence of these foci in all or most of the glands in the specimen is the characteristic microscopic feature of Sjögren’s syndrome in the minor salivary glands. These histopathological changes represent the hallmark of this disorder [8].

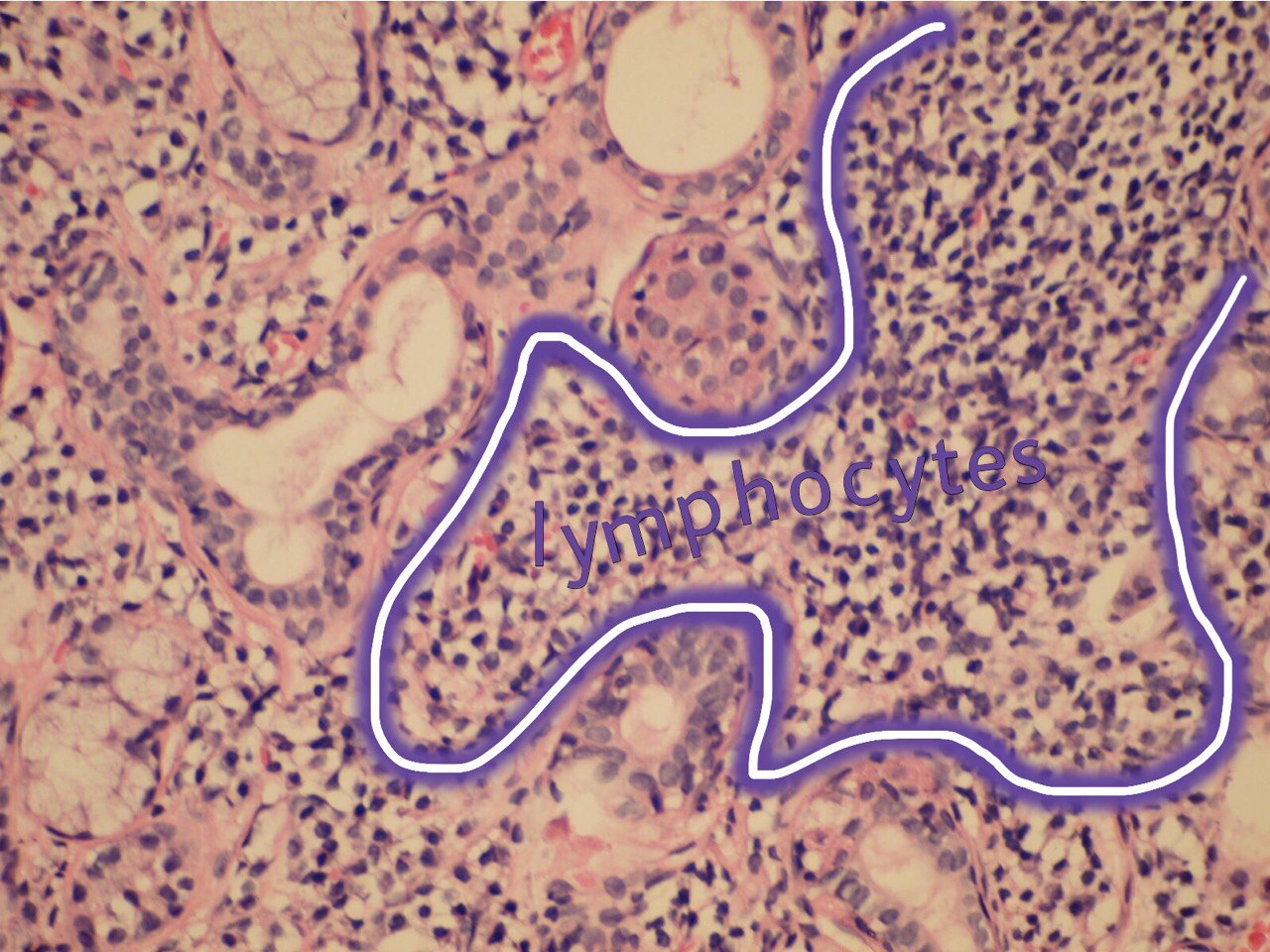

The infiltrate should consist predominantly of lymphocytes (Fig 5). The study showed that the prevalent cells in the minor labial salivary gland infiltrate were those bearing the T-helper phenotype (CD4+). These T cells also express the adhesion molecule LFA-1 (lymphocyte function associated molecule) and other T cell markers, such as CD2 and LFA-3, which mediate an antigen independent interaction and are up-regulated after lymphocytic activation. B cells constitute approximately 20% of the total infiltrating population, while NK cells are rarely observed. There may be admixed plasma cells and histiocytes, but these cells should not comprise a significant portion of the infiltrate. Granulomatous inflammation should not be present. Uncommonly, epimyoepithelial islands may occur in minor salivary glands of patients affected by Sjögren syndrome.

The Sjögren syndrome focus score is a semiquantitative method of grading the degree of salivary gland inflammatory infiltration [9]. Histomorphometric analysis is utilized by the pathologist to quantitate the area of salivary gland parenchyma in square millimeters, by counting the number of lymphocytic aggregates. The focus score represents the number of lymphocytic aggregates per 4 square millimeters, and therefore an absolute minimum of 4 square millimeters of salivary gland tissue is required to calculate the focus score. A focus score of 1 or greater is considered supportive the diagnosis of Sjögren syndrome. The focus score can range from 0 to 12, with a focus score of 12 representing diffuse glandular effacement by the lymphocytic infiltrate and a score 0 referring to the absence of these cells. The presence of a dense effacing infiltrate should raise concern for possible progression to lymphoma.

The focus score has been validated as a histological index of severity of the salivary gland involvement in Sjögren syndrome [10]. A series of studies have correlated the presence of high focus scores with indices of local or systemic disease activity. The presence of a higher focus score has been found to correlate with acinar damage, presence of anti-SSA/B serology (12 times higher among those with focus score >1 than among those with focus score <1), and the presence of specific extraglandular features such as Raynaud’s phenomenon, vasculitis, lymph node or spleen enlargement and leucopenia. A focus score >1 has also been found to correlate with positive RF serology, high ANA titers and IgG concentrations, the presence of keratoconjunctivitis sicca and low unstimulated but not stimulated salivary flow rates. More recently, it has been established that a high focus score (>3) has a significant predictive value for the development of non-Hodgkin B cell lymphoma [11].

In our study, the focus score in the group of the examined patients who presented with a positive lip minor salivary gland biopsy, was extended from 1 to 6.42 with the highest values seen in patients with Sjögren syndrome without associated connective tissue disease (primary Sjögren syndrome). It was also pointed out that the focus score cannot separate early from late disease as chronicity of symptoms and focus score did not show a relationship.

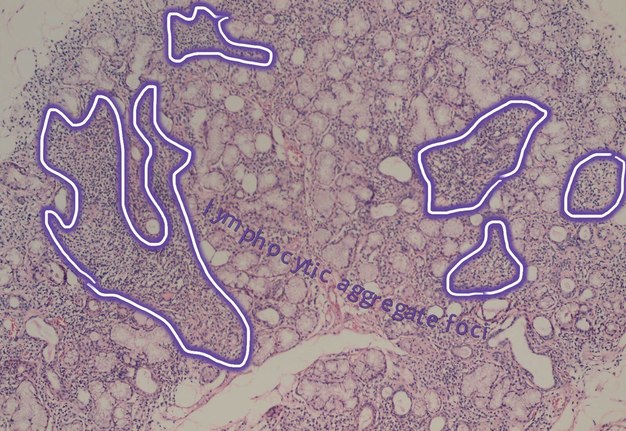

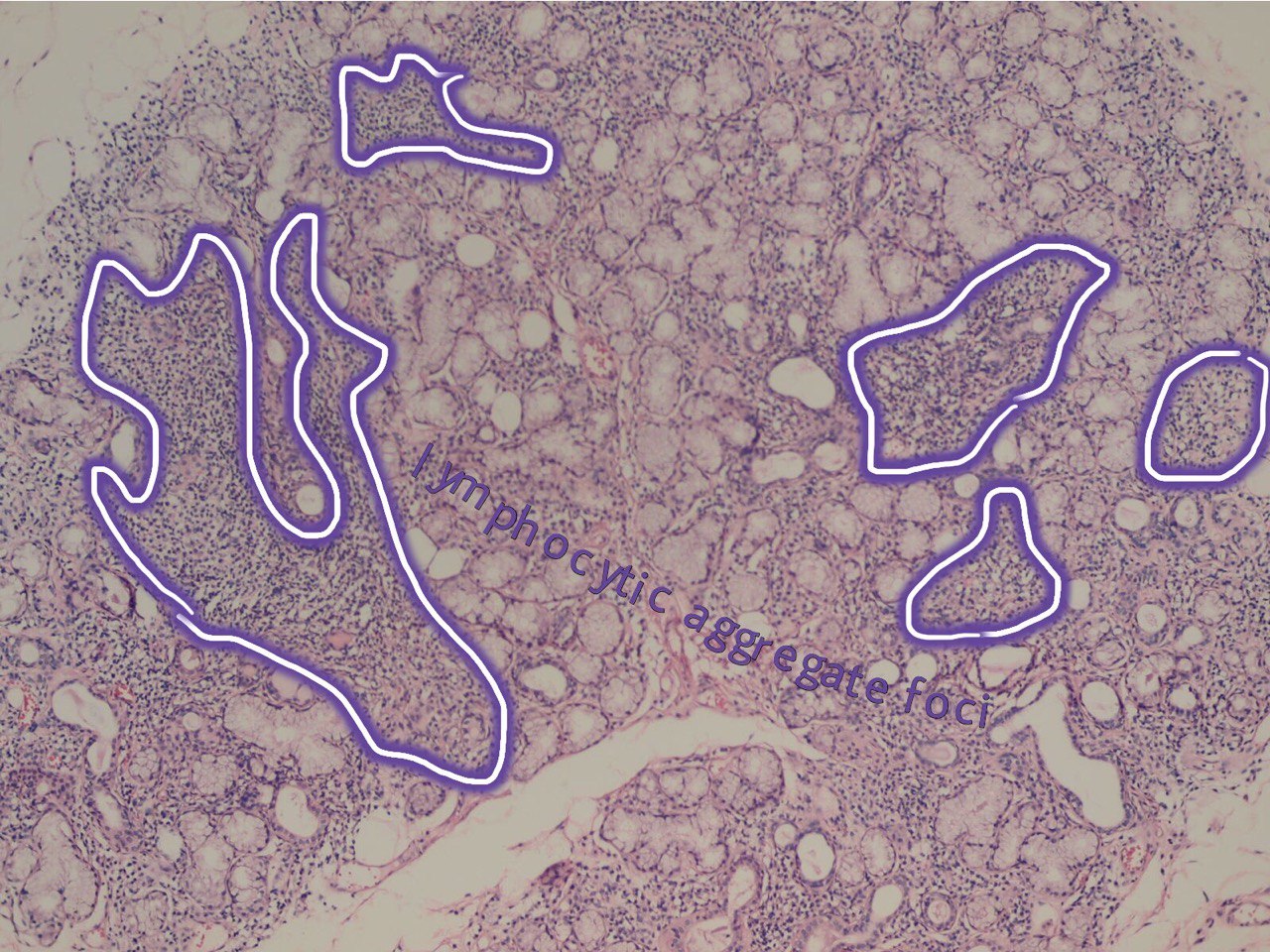

FIGURE 4A. (A) Image without notations. Minor salivary gland with multiple lymphocytic aggregate foci (hematoxylin and eosin stain, × 200). (B) Image with notations. Minor salivary gland with multiple lymphocytic aggregate foci (the lymphocytic aggregate foci are indicated with purple-white lines and words lymphocytic aggregate foci).

FIGURE 4B. (A) Image without notations. Minor salivary gland with multiple lymphocytic aggregate foci (hematoxylin and eosin stain, × 200). (B) Image with notations. Minor salivary gland with multiple lymphocytic aggregate foci (the lymphocytic aggregate foci are indicated with purple-white lines and words lymphocytic aggregate foci).

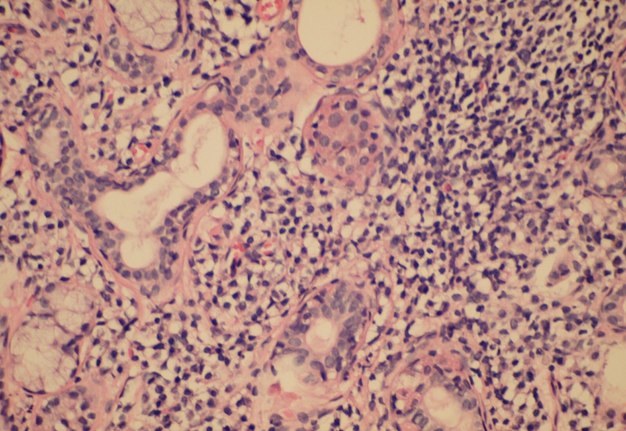

FIGURE 5A. (A) Image without notations. Section showing a dense aggregate of lymphocytes with adjacent intact salivary gland parenchyma (hematoxylin and eosin stain, × 400). (B) The same image with notations. Section showing a dense aggregate of lymphocytes (the lymphocytes are indicated with purple-white lines and words lymphocytes) with adjacent intact salivary gland parenchyma.

FIGURE 5B. (A) Image without notations. Section showing a dense aggregate of lymphocytes with adjacent intact salivary gland parenchyma (hematoxylin and eosin stain, × 400). (B) The same image with notations. Section showing a dense aggregate of lymphocytes (the lymphocytes are indicated with purple-white lines and words lymphocytes) with adjacent intact salivary gland parenchyma.

Minor salivary gland lip biopsy results report a useful diagnostic value in Sjögren syndrome. They should be carefully addressed in the overall diagnostic procedure due to inconsistencies of sensitivity and specificity. Whilst the focus score has been proven as a functional diagnostic and prognostic tool, it presents obvious limitations.

First, the stability of the focus score in repeated biopsies over a long period of time is not fully established. In a recent study, surprisingly, in 12% of the cases the second evaluation by trained pathologists led to a diagnosis change. Minor salivary gland infiltration may also be revealed in patients affected by myasthenia gravis, sialolithiasis and other autoimmune disorders not associated with sicca symptoms [12].

In addition, the extent of infiltrate in a lip biopsy using the same methodological approach may vary greatly from gland to gland in a single patient. Further, if the density of infiltrate is severe, the foci may become confluent, hindering focus score determination.

Whilst the last studies, in particular the correlation between a higher focus score and the development of lymphoma, suggest stability of the histological lesions over a period of time, this has not been proven in large cohorts. Moreover the sensitivity of focus score is reduced in smokers and in patients taking corticosteroids. The combination of focus score >1 and immunological staining for IgA has been shown to increase the diagnostic specificity for Sjögren syndrome. Indeed, the presence of a focus score >1 and quantitative immunohistological staining of IgA <70%, had greater sensitivity and specificity that the focus score alone.

The focus score, although giving an idea of the extent of the cellular infiltrate, fails to provide discrete data on the foci size (indeed, for larger or confluent foci a focus score of 12 is arbitrarily used). This aspect, while not critically determinant for the histological diagnosis of Sjögren syndrome, could represent a problem for the use of the focus score as an outcome measure in clinical trials in which subtle changes in foci size might not be accurately reported in the focus score. The introduction of additional measurements such as average of focus area, area of lymphocytic infiltration and evaluation of the degree of organization to augment the information provided by the simple focus score is currently debated in the Sjögren syndrome community.

Conclusion

The oral labial minor salivary gland biopsy is a valuable diagnostic tool for the establishment of Sjögren syndrome diagnosis. However, a positive Sjögren syndrome focus score is not diagnostic of Sjögren syndrome by itself, but the results of the biopsy must be correlated with each of the other diagnostic criteria in order to establish an accurate diagnosis. In addition, a number of patients with negative lip biopsy, (focus score less than 1) can end up with a confirmed diagnosis supporting the Sjögren syndrome. Furthermore, the minor salivary gland biopsy is also helpful in excluding other conditions, such as sarcoidosis, which may be associated with a sicca syndrome, or sialosis.

In conclusion, despite the lack of agreement in the parameters considered when evaluating salivary gland biopsies, histology remains the gold standard for diagnosis of Sjögren syndrome and has the potential to become the most reliable biomarker in clinical studies. However, the heterogenicity of the measurements might present the potential risk of compromising the combined analysis of different trials. The current interest in designing clinical trials in Sjögren syndrome will therefore require a combined effort of rheumatologists and oral medicine specialists to discuss these aspects and define consensus guidelines on the methodology and use of the salivary gland biopsy analysis in clinical trials.

This increased awareness will help to reduce the time to diagnosis, to direct the treatment from symptomatic, at the exact etiology behind the disease (tissue specific receptors), and to preserve the health and quality of life of patients with Sjögren syndrome [13].

References (13)

-

Hansen A, Lipsky PE, Dorner T. New concepts in the pathogenesis of Sjögren syndrome: many questions, fewer answers. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2003;15(5):563―70.Crossref

-

Marx RE, Stern D. Oral and maxillofacial pathology: a rationale for diagnosis and treatment. 2nd ed. Hanover Park, IL: Quintessence Publishing Co; 2012.Crossref

-

Mandel L, Dehlinger N. Systemic manifestations and Sjögren syndrome. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2003;61:1358―61.Crossref

-

Calman HI, Reifman S. Sjögren’s syndrome: report of a case. J Oral Pathol 1966;21:158―62.Crossref

-

Al-Hashimi I. The management of Sjögren’s syndrome in dental practice. J Am Dent Assoc 2001;132(10):1409―17.Crossref

-

Daniels TE, Benn DK. Is sialography effective in diagnosing the salivary component of Sjögren’s syndrome? Adv Dent Res 2006;10:25―8.Crossref

-

Lee M, Rutka JA, Slomovic AR, et al. Establishing guidelines for the role of minor salivary gland biopsy in clinical practice for Sjögren syndrome. J Rheumatol 1998;25:247―53.Medline

-

Vitali C, Bombardier S, Jonsson R, et al. Classification criteria for Sjogren’s syndrome: a revised version of the European criteria proposed by the American European group. Ann Rheum Dis 2002;61:554―8.Crossref

-

Chisholm DM, Mason DK. Labial salivary gland biopsy in Sjogren’s disease. J Clin Pathol 2008;21:656―60.Crossref

-

Pijpe J, Kalk WW, van der Wal JE, et al. Parotid gland biopsy compared with labial biopsy in the diagnosis of patients with primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Rheumatology 2007;46:335―41.Crossref

-

Daniels TE. Labial salivary gland biopsy in Sjogren’s syndrome: assessment as a diagnostic criterion in 362 suspected cases. Arthritis Rheum 1994;27:147―56.Crossref

-

Hansen A, Lipsky PE, Dorner T. Immunopathogenesis of Sjogren’s syndrome: implications for disease management and therapy. Curr Opin Rheum 2005;17:558―65.Crossref

-

Ramos-Casals, Stone M, Moutsopoulos HM. Sjögren’s syndrome: diagnosis and therapeutics. Berlin: Springer; 2012.