Cine Loops in Ultrasonographic Verification of Acquired Lymphatic Malformation (Lymphangioma) of the Neck Associated with Musical Instrument (Violin) Play: A Case Report

March 31, 2025

J Diagn Treat Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2025; 9: 100303.

DOI: 10.23999/j.dtomp.2025.3.100303

Under a Creative Commons license

HOW TO CITE THIS ARTICLE

Cherniak OS, Demidov VH, Blyzniuk VP, Zaritska VI, Snisarevskyi PP. Cine loops in ultrasonographic verification of acquired lymphatic malformation (lymphangioma) of the neck associated with musical instrument (violin) play: A case report. J Diagn Treat Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2025 Mar;9(3):100303. https://doi.org/10.23999/j.dtomp.2025.3.100303

NATIONAL REPOSITORY OF ACADEMIC TEXTS

https://nrat.ukrintei.ua/en/searchdoc/2025U000026/

SUMMARY

Lymphatic malformation (LM) is a rare pathology that is predominantly congenital. However, an increasing number of published cases clearly demonstrate the possibility of developing acquired LM, mainly because of trauma. Causes of injury can include dental restorations in the oral cavity, repetitive surgeries, and even chronic trauma from playing musical instruments. This article presents the case of a 32-year-old female with an acquired lymphatic neoplasm of the neck that developed because of many years of violin playing. Clinical preoperative photography, gray scale and color Doppler ultrasonography data, two ultrasound videos (cine loops), a specimen of the excised mass, and histopathological images are presented. Thus, this paper confirms the possibility of developing acquired LM in the neck region. The fact that the LM developed to its current size by the patient's 32nd year of life, in addition to the patient’s musical history, confirms that the development and growth of this acquired LM required time, namely years of playing a violin. Also, two ultrasound videos clearly demonstrate the capabilities of this dynamic examination for verifying this rare pathology. Ultrasound videos show the ability of this lymphatic neoplasm to compress and reduce in size by 2 times. Since LM is a term that refers to a developmental defect of the lymphatic system, we suggest using the term "lymphangioma" for acquired lymphatic formation (i.e., lymphatic neoplasm).

KEY WORDS

Lymphatic malformation, lymphangioma, lymphatic neoplasm, neck, ultrasonography, gray-scale ultrasound, color Doppler ultrasound, cine loop in ultrasonography, violin

INTRODUCTION

Specialists of various profiles may be confused about which diagnosis is correct to use as of 2025 when describing a lymphatic mass of the head and neck area¾lymphatic malformation (LM) [1-3] or lymphangioma [4-6]. Both terms are found in modern literature, but the second term is increasingly being abandoned [7]. Most sources state that the LM is a rare, non-malignant mass consisting of fluid-filled channels or spaces thought to be caused by the abnormal development of the lymphatic system [7]. Although numerous authors describe LM as a benign lesion, Yu et al. (2022) have proven that the unusual process of LM gradual malignant transformation into lymphangiosarcoma is also possible [8]. Also, as some authors describe LM as a congenital pathology [1, 5, 7, 9], others provide evidence that it may be an acquired factors for the LM appearance [10, 11]. Direct confirmation of the data on a possible variant of acquired LM of the neck is the data of the patient presented in this article.

The aims of this article are (1) to publish the world's first ultrasound videos of the spongy structure and ease compressibility of an acquired LM of the neck associated with many years of playing the violin, (2) to expand diagnostic options of oral and maxillofacial surgeons.

CASE REPORT

On June 25, 2014, a 32-year-old Caucasian female was referred to the Center of Maxillofacial Surgery and Dentistry with complaints of a tumor on her neck (Fig 1) that was protruding and creating a cosmetic problem. Clinically, the neoplasm was painless and easily compressible upon palpation, the overlying skin was normal. According to the patient and her relatives, this mass has become noticeable over the past few years. The key information in the medical history is that the patient has been playing the violin for many years. Since many sources publish that musicians may have occupational diseases associated with playing a certain type of musical instrument [12-14].

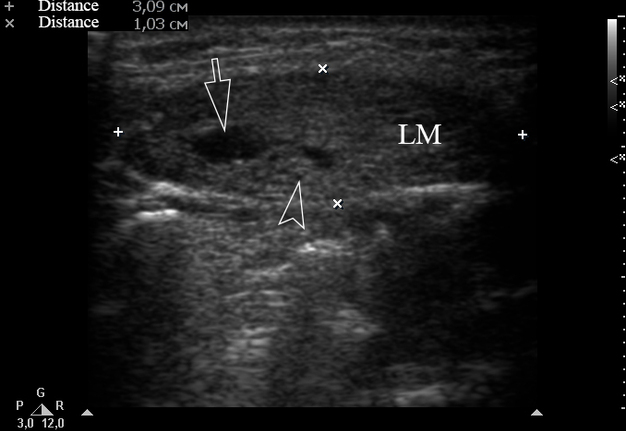

Ultrasonography (USG) was performed using HD11 XE model of ultrasound machine (Philips Healthcare, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) with 12-3 MHz linear probe (synonym: linear transducer). USG showed well-circumscribed heterogeneous hypoechoic lesion measured 3.09 cm x 1.03 cm (Fig 2) and which was located slightly above the middle third of the neck between the midline of the neck and the anterior margin of the left sternocleidomastoid muscle.

FIGURE 2. Longitudinal gray-scale ultrasound (i.e., B-mode ultrasound) of a lymphatic malformation (LM) demonstrates a well-circumscribed lesion in a slightly compressed state. Open arrow indicates larger cystic cavity and open arrowhead labels smaller cystic cavity inside the malformation. The LM measured 3.09 cm x 1.03 cm (indicated by “+” and “×” calipers). The depth of the ultrasound-scanned tissues is 3 cm, as indicated by the vertical scale with marks on the right.

The formation had cystic cavities of various sizes from medium to very small. Cystic areas visualized as different size anechoic areas. An important feature of this formation was its ability to almost completely compress.

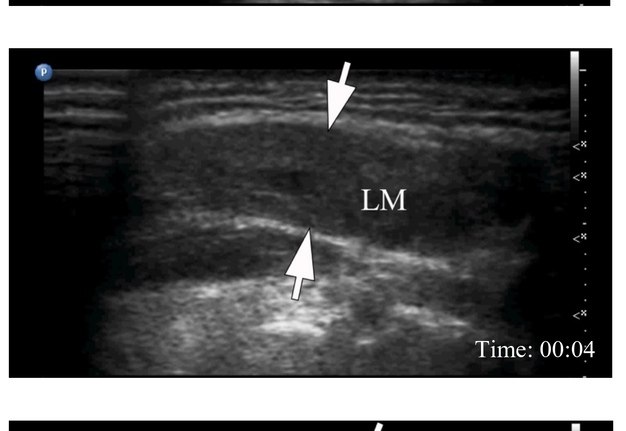

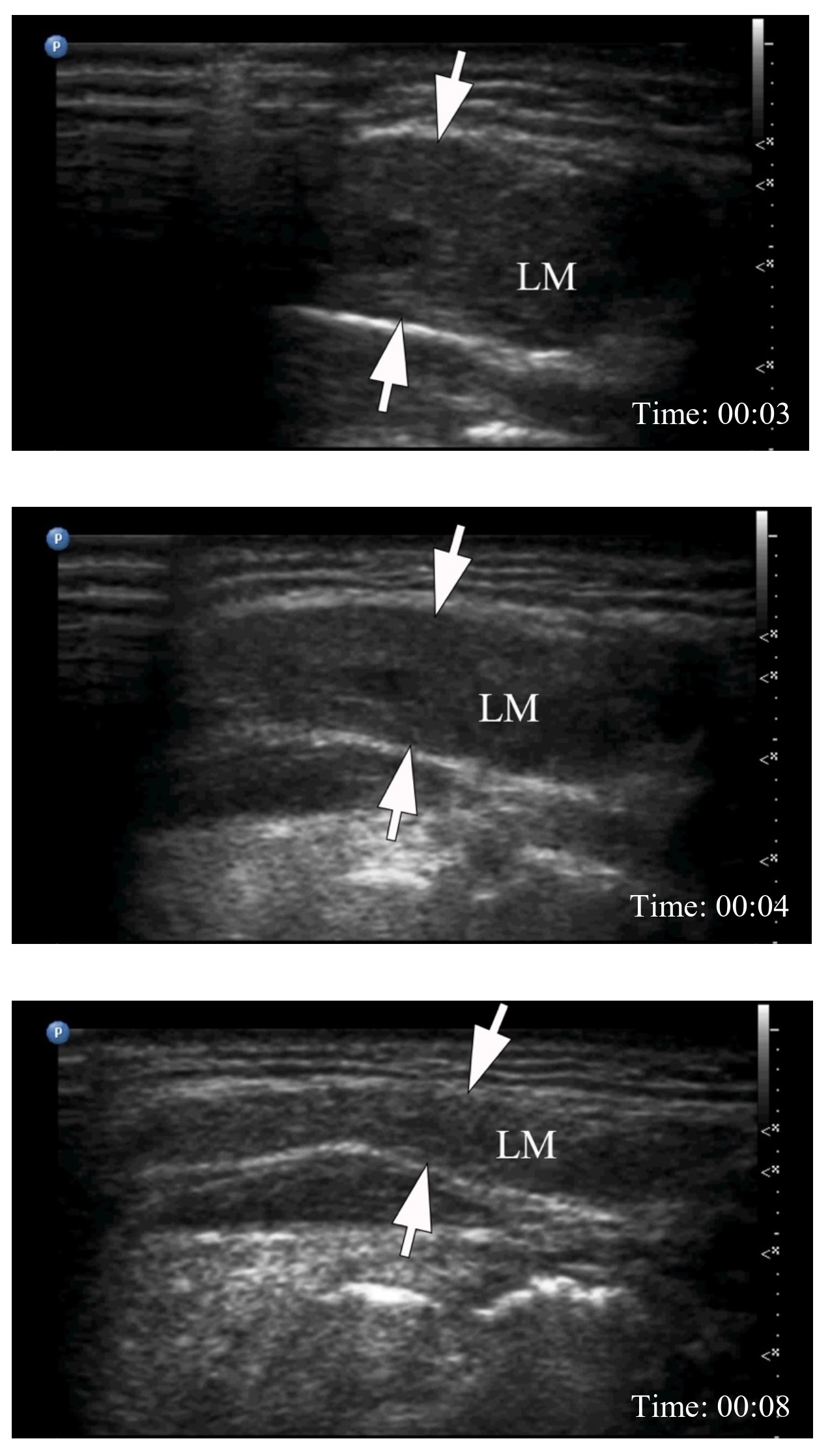

Supplemental Video Content 1 (cine loop) demonstrates the degree of compression of the malformation by the ultrasound transducer when performing gray-scale USG. Screenshots from cine loop demonstrate LM in three states: non-compressed, moderately compressed, and completely compressed. Video is available in the page of the full-text article on dtjournal.org and in the YouTube channel, available at https://youtu.be/1A30SbP0Tsg. Total video’s duration is 33 seconds.

VIDEO 1. Cine loop of a gray-scale ultrasonography of lymphatic malformation (LM) of the neck. Screenshots show the LM in three states: non-compressed (A), moderately compressed (B), and completely compressed (C). Arrows indicate margins of the LM (i.e., lymphangioma). Compression was performed with a linear probe (i.e., linear transducer). Video is available in the page of the full-text article on www.dtjournal.org and in the YouTube channel ‘Videos of JDTOMP,’ available at https://youtu.be/1A30SbP0Tsg. The letter “P” on a blue circle in the upper left corner of the sonograms indicates the probe’s side. Total video’s duration: 33 sec. Video time of the screenshots are: 03 sec, 04 sec, and 08 sec.

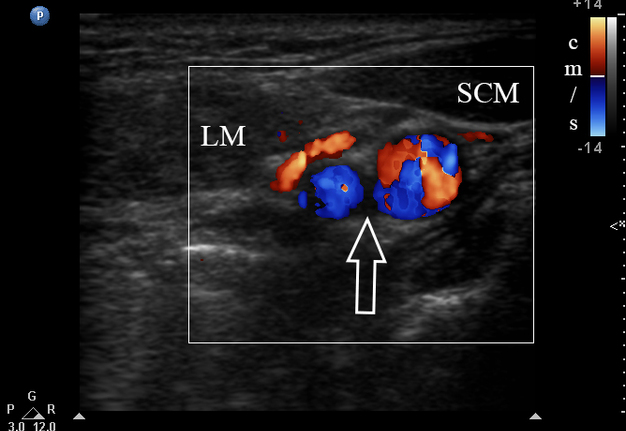

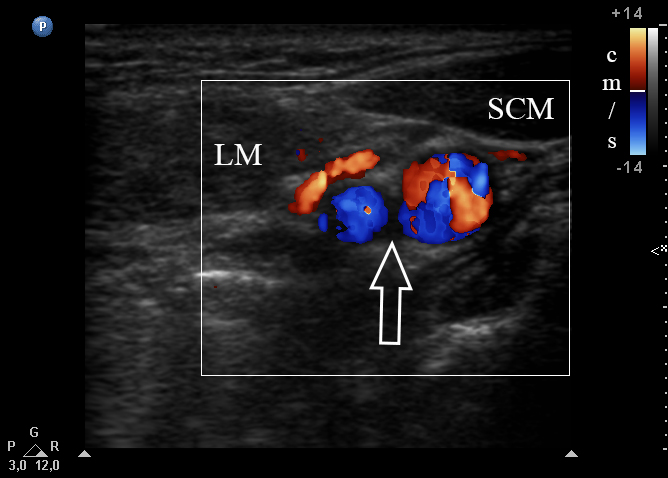

Lesion had no arterial or venous blood flow upon color Doppler USG (Fig 3). The formation was adjacent to such a muscle as omohyoid and was located close to the anterior margin of the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

FIGURE 3. Color Doppler ultrasound of the left neck shows the relationship between the lymphatic malformation (LM), left sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle, and the main neurovascular structures of the neck (also known as neurovascular bundle of the neck). This neurovascular bundle (open arrow) is surrounded by carotid sheath which at different levels contains structures such as common and internal carotid artery, internal jugular vein, vagus nerve, etc. The letter “P” on a blue circle in the upper left corner of the sonogram indicates the probe’s side.

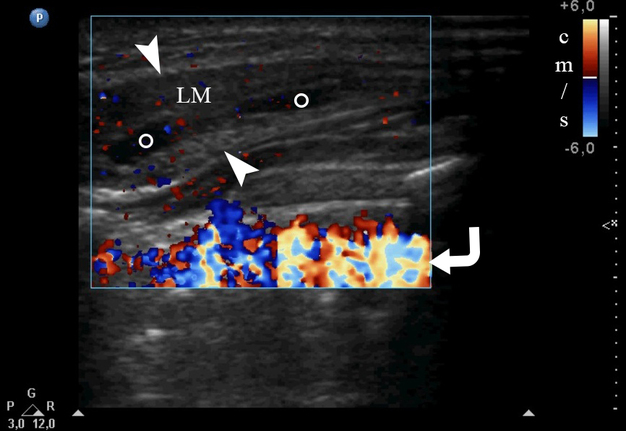

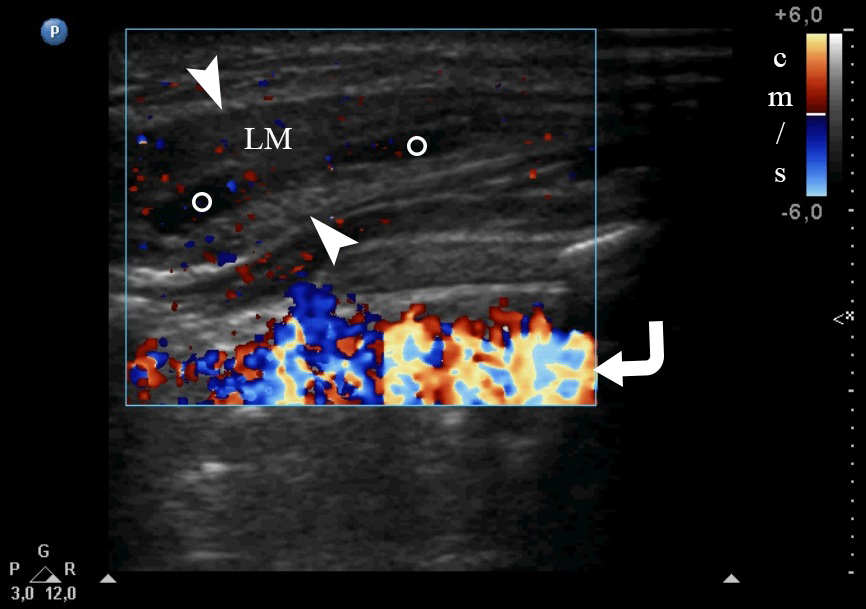

Supplemental Video Content 2 (cine loop) demonstrates the degree of compression of the malformation by the ultrasound transducer when performing color Doppler USG. Video is available in the page of the full-text article on dtjournal.org and in the YouTube channel, available at https://youtu.be/bliMTnSMCs0. Total video’s duration is 27 seconds.

VIDEO 2. Cine loop of a color Doppler ultrasonography of lymphatic malformation (LM) the neck. A screenshot from the cine loop demonstrates the possibility of complete compression of the LM (arrowheads) with an ultrasound probe. Cystic areas within LM are labeled by circles. Screenshot demonstrate LM state upon moderate compression. Notes no blood flow inside the malformation. Ultrasound artifact is indicated by curved arrow. The “P” letter at the upper left corner of the screenshot of the cine loop indicates the probe’s side. Video is available in the page of the full-text article on www.dtjournal.org and in the YouTube channel ‘Videos of JDTOMP,’ available at https://youtu.be/bliMTnSMCs0. Total video’s duration: 27 sec. Video time of the image: 01 sec.

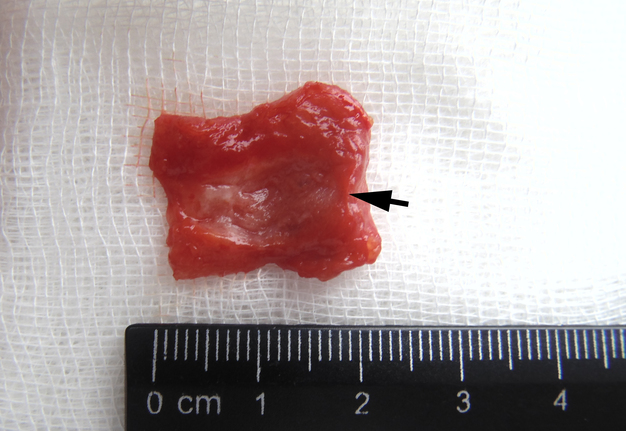

The operation was performed under general anesthesia and the mass was excised within healthy tissues. At the lancing of the excised mass, was noted its spongy structure (Fig 4) and the fact that the entire lesion was filled with gray fluid (i.e., lymph).

Histopathology (Fig 5) was performed by two experienced doctors-pathologists, V.I.Z. (26 years of experience) and P.P.S (21 years of experience). It showed the lymph in the lumens of the lymphatic vessels and multiple oval-shaped endothelial cells (visualized as small inclusions with dark blue color) in the inner layer of the lymphatic vessels. A histopathological diagnosis of lymphangioma (i.e., LM) was made.

The patient continued to be recurrence-free at her 3-year follow-up.

DISCUSSION

Lymphangiomas belong to the category of vascular malformations in the Mulliken and Glowacki classification system and are dilated endothelial-lined lymphatic spaces (Yuen and Ahuja, 2012) [15]. The authors classify all types of lymphangiomas as congenital LMs (Gilony et al., 2012; and Kim, 2014) [16, 17]. A characteristic feature of LM is its compressibility with changes in the shape and configuration of the lesion [6]. Fluctuation can be detected during palpation of cystic cavities, and a puncture can yield a clear liquid, sometimes cloudy, often with an admixture of blood [6].

The neck area is one in which there can potentially be noted a wide variety of neoplasms and malformations. Differential diagnosis of LM of the neck is carried out with hemolymphangioma [6, 18], arteriovenous malformation [15, 19], branchial cleft and thyroglossal duct cysts [15, 20], cystic squamous cell carcinoma [20], metastatic nodes [15], nerve sheath tumor [15], etc. USG, as a non-invasive diagnostic method, allows an early diagnosis to be made with fairly high accuracy [15, 21, 22]. Johnson et al. (2020) are more than right when they say that the use of USG has gained momentum because of its accessibility, cost efficiency, quicker collection time [23], and safety. The efficiency of ultrasonography in the detection of cystic and solid components in neoplasms is described in detail in numerous sources [15, 20]. So, USG was an excellent dynamic imaging tool to establish a preliminary diagnosis in the case we described. The described ultrasound characteristics of LM in our patient corresponded to the classic manifestations of LM with cystic cavities of the mixed type [15]. However, according to our knowledge, these are the first two published videos (cine loops) of the possibility of full compression of LM of the neck. Moreover, according to our literature search, this is the first thoroughly described acquired LM caused by prolonged (over many years) violin playing.

Left-sided “submandibular” lesions develop in 62% of violinists and violists from holding their instrument (Blum and Ritter, 1990; Ostwald et al. 1994) [12, 13].

According to Blum and Ritter (1990), in four cases of their observations of the viola and violin players the “tumor” revealed itself not just an induration but as a sialolithiasis of the submandibular gland, and in one case as a cystadenolymphoma of the parotid gland (i.e., Warthin’s tumor) [12]. Therefore, we believe that in this article it is worth paying attention to the ultrasound picture of cystadenolymphomas too [24].

Moraes and Antunes (2012) are emphasizing, the neck, shoulder, and temporomandibular joints are the most affected areas, due to prolonged flexion of the head and shoulder required to hold the violin [14]. Thus, our case not only confirms the statistics of the harmful effects of prolonged playing of certain instruments, but also is the first case of acquired LM described in detail in a patient who was professionally engaged in playing the violin.

Colbert et al. (2013) define LMs of the neck as a diverse group of lymphatic lesions [1]: They can be small and superficial or large and extensive, and management can be a challenge.

Cine loops in USG [23, 25] are an extremely useful method for dynamic diagnosis of the structure of malformations, tumors, and pathologic conditions. The two videos presented above clearly demonstrate this in both B-mode and color Doppler USG.

According to Gilony et al. (2012) and Kim (2014), for the microcystic and mixed types of LMs (which are also termed as lymphangiomas), surgery should be considered rather than sclerotherapy [16,17]. The same approach was used in our case, namely, the LM was excised within visually healthy tissues.

Treatment decision algorithms for stage I, II, III, IV, and V LMs are described in a study by Perkins et al. (2010) [26].

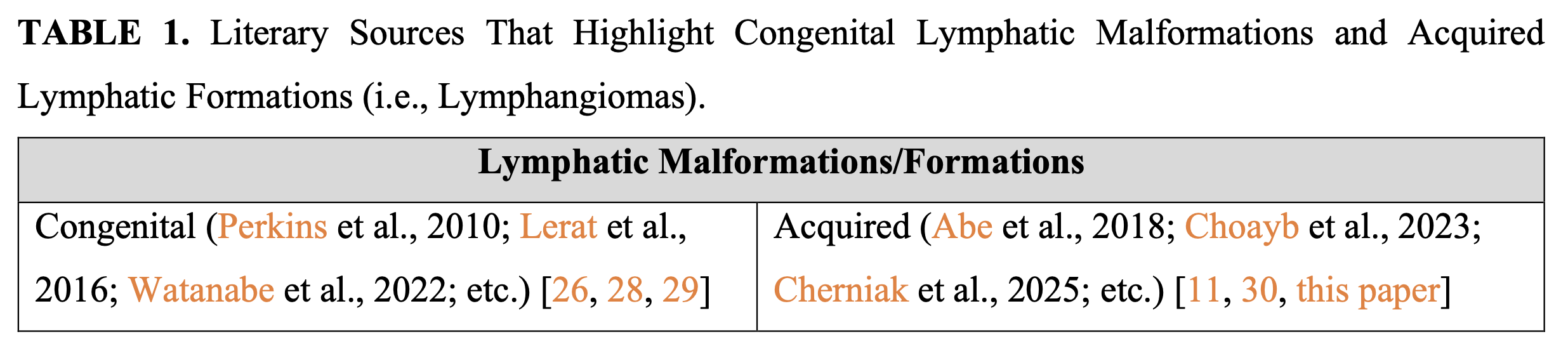

So, this article is additional confirmation of the emergence of playing-related (i.e., acquired) formations of the neck [12, 13]. And this is in addition to other playing-related musculoskeletal disorders [27]. Table 1 clearly demonstrates references to literary sources that highlight cases of both congenital and acquired LMs (i.e., lymphatic formations of lymphangiomas). Perhaps some authors would consider it appropriate to describe this pathological process in the patient as acquired lymphedema [31].

CONCLUSION

Thus, this article confirms the possibility of developing acquired LM in the neck region. The fact that the LM developed to its current size by the patient's 32nd year of life, in addition to the patient’s musical history, confirms that the development and growth of this acquired LM required time, namely years of playing a violin. Also, two ultrasound videos clearly demonstrate the capabilities of this dynamic examination for verifying this rare pathology. Since LM is a term that refers to a developmental defect of the lymphatic system, we suggest using the term "lymphangioma" for acquired lymphatic formation.

TERM OF CONSENT

Writing patient’s consent was obtained for publication the photos and data.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

Drafting of the manuscript: Cherniak OS, Blyzniuk V. Critical revision of the manuscript: all authors. Approval of the final version of the manuscript: all authors.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

FUNDINGS

No funding was received for this study.

REFERENCES (31)

-

Colbert SD, Seager L, Haider F, et al. Lymphatic malformations of the head and neck-current concepts in management. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;51(2):98-102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjoms.2011.12.016

-

Yang W, Wang H, Xie C, et al. Management for lymphatic malformations of head and neck. Front Neurol. 2024;15:1450102. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2024.1450102

-

Tokarski M, Wierzbicka M. Giant lymphangioma of supraclavicular region mimicking branchial cleft cyst. Postępy w chirurgii głowy i szyi/Advances in Head and Neck Surgery. 2013;12(1):14-17. In Polish.

-

Al Qooz F, Alanezi M, Al Olaimat MS, et al. Supraclavicular cavernous lymphangioma: A rare entity. Oral Maxillofac Surg Cases. 2023 Jun;9(2): 100313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omsc.2023.100313

-

Kandakure VT, Thakur GV, Thote AR, Kausar AJ. Cervical lymphangioma in adult. Int J Otorhinolaryngol Clin. 2012;4(3):147-150. https://doi.org/10.5005/jp-journals-10003-1101

-

Tymofieiev OO. Manual of oral and maxillofacial surgery. 5th ed. Kyiv: Chervona Ruta-Turs; 2012.

-

National Organization of Rare Disorders. Ganti S, Perkins JA. Lymphatic malformations [internet]. 2021 Jun [cited 2025 Jan 16]. Available from: https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/lymphatic-malformations/

-

Yu H, Mao Q, Zhou L, Li J, Xu X. Rare case of cystic lymphangioma transforming into lymphangiosarcoma: A case report. Front Oncol. 2022 Feb;12:814023. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.814023

-

Klibngern H, Ariyanon T, Pornchaisakuldee C, et al. A Large adult postcricoid lymphatic malformation: A case report and literature review. Ear Nose Throat J. Published online February 6, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1177/01455613241229979

-

Allen JG, Riall TS, Cameron JL, Askin FB, Hruban RH, Campbell KA. Abdominal lymphangiomas in adults. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006 May;10(5):746-751. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gassur.2005.10.015

-

Abe A, Kurita K, Ito Y. Acquired lymphatic malformations of the buccal mucosa: A case report. Clin Case Rep. 2018 Aug;6(10):1929-1932. https://doi.org/10.1002/ccr3.1756

-

Blum J, Ritter G. Violinists and violists with masses under the left side angle of the jaw known as “fiddler’s neck”. Med Probl Perform Art. 1990;5(4):155-160.

-

Ostwald PF, Baron BC, Byl NM, Wilson FR. Performing arts medicine. West J Med. 1994;160(1):48-52.

-

Moraes GF, Antunes AP. Musculoskeletal disorders in professional violinists and violists. Systematic review. Acta Ortop Bras. 2012;20(1):43-47. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-78522012000100009

-

Yuen HY, Ahuja AT. Benign clinical conditions in the adjacent neck. In: Ultrasound of the thyroid and parathyroid glands. Sofferman RA, Ahuja AT, editors. Springer Science + Business Media; 2012:229-259. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-0974-8_11

-

Gilony D, Schwartz M, Shpitzer T, et al. Treatment of lymphatic malformations: a more conservative approach. J Pediatr Surg. 2012 Oct;47(10):1837-1842. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.06.005

-

Kim JH. Ultrasound-guided sclerotherapy for benign non-thyroid cystic mass in the neck. Ultrasonography. 2014 Apr;33(2):83-90. https://doi.org/10.14366/usg.13026

-

Demidov VH, Cherniak OS. Hemolymphangioma of the neck. J Diagn Treat Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2022 Aug;6(8):114-116. https://doi.org/10.23999/j.dtomp.2022.8.2

-

Nozhenko OA, Savchuk LA, Zaritska VI, et al. Phleboliths, not sialoliths: a report of submandibular gland arteriovenous malformation with numerous calcifications: analysis of cine images and literature review for the 54 years. J Diagn Treat Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2023 Jul;7(7):63-86. https://doi.org/10.23999/j.dtomp.2023.7.1

-

Tymofieiev OO, Fesenko II, Cherniak OS, Zaritska VI. Features of diagnostics, clinical course and treatment of the branchial cleft cysts. J Diagn Treat Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2017;1(1):15–31. https://doi.org/10.23999/j.dtomp.2017.1.3

-

Mittal A, Anand R, Gauba R, et al. A step-by-step sonographic approach to vascular anomalies in the pediatric population: A pictorial essay. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2021 Jan;31(1):157-171. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0041-1729486

-

Gritzmann N, Hollerweger A, Macheiner P, Rettenbacher T. Sonography of soft tissue masses of the neck. J Clin Ultrasound. 2002 Jul-Aug;30(6):356-373. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcu.10073

-

Johnson AW, Stoneman P, McClung MS, et al. Use of cine loops and structural landmarks in ultrasound image processing improves reliability and reduces error in the assessment of foot and leg muscles. J Ultrasound Med. 2020 Jun;39(6):1107-1116. https://doi.org/10.1002/jum.15192

-

Cherniak OS, Savchuk LA, Ripolovska OV, et al. Ultrasonographic identification of the parotid cystadenolymphoma (Warthin’s tumor) by oral and maxillofacial surgeons: supplement to the Matsuda and colleagues’ classification. J Diagn Treat Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2022 Jul;6(7):92–110. https://doi.org/10.23999/j.dtomp.2022.7.1

-

Marangelli V, D’ambrosio G, Carella L, et al. Digital cine loop technology. In: Iliceto S, Rizzon P, Roelandt JRTC, editors. Ultrasound in coronary artery disease. Amsterdam: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1991:95-105. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-0611-2_10

-

Perkins JA, Manning SC, Tempero RM, et al. Lymphatic malformations: review of current treatment. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010 Jun;142(6):795-803.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otohns.2010.02.026

-

Berezutska M, Berezutsky V. Professional injuries in musicians’ hands: The perennial problem. Musicological Thought of Dnipropetrovsk Region. 2021 Dec;21(2):486-528. In Ukrainian. https://doi.org/10.33287/222161

-

Lerat J, Mounayer C, Scomparin A, et al. Head and neck lymphatic malformation and treatment: Clinical study of 23 cases. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2016 Dec;133(6):393-396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anorl.2016.07.004

-

Watanabe S, Funato Y, Miyata M, Suzuki, T. A neonatal large neck lymphatic malformation successfully treated with Eppikajyutsuto. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep. 2022 Mar;78:102174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsc.2022.102174

-

Choayb S, Jidal M, Zahi H, et al. Acquired cystic lymphangioma imitating breast cancer recurrence. Radiol Case Rep. 2023 Jun;18(8):2707-2710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radcr.2023.05.018

-

Sleigh BC, Manna B. Lymphedema. [Updated 2023 Apr 19]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537239/

ARTICLE TITLE IN UKRAINIAN

Кінопетлі в ультразвуковій верифікації набутої лімфатичної мальформації (лімфангіоми) шиї, пов’язаної з грою на музичному інструменті (скрипці): опис випадку

SUMMARY IN UKRAINIAN. SUMMARY IN UKRAINIAN (PDF).

Лімфатична мальформація (ЛМ) – це рідкісна патологія, переважно вроджена. Проте все більше опублікованих випадків чітко демонструють можливість розвитку набутої ЛМ, головним чином через травму. Причинами травми можуть виступати, як стоматологічні конструкції в порожнині рота, повторювані операції, так навіть і хронічна травма викликана грою на музичних інструментах. У цій статті представлено випадок 32-річної жінки з набутим лімфатичним новоутворенням шиї, яке розвинулося внаслідок багаторічної гри на скрипці. Наведено клінічні передопераційні фотографії, дані ультразвукової діагностики (УЗД) в B-режимі та режимі кольоровокго Доплерівського картування (КДК), два відео (кінопетлі) УЗД, видалену пухлину та патогістологічне зображення. Таким чином, дана робота підтверджує можливість розвитку набутої ЛМ в області шиї. Той факт, що ЛМ розвинувся до свого поточного розміру до 32-го року життя пацієнта, на додаток до музичної історії пацієнта, підтверджує, що розвиток і зростання цієї набутої ЛМ вимагав часу, а саме років гри на скрипці. Також два відео УЗД наочно демонструють можливості цього динамічного обстеження для верифікації цієї рідкісної патології. Відеопетлі УЗД показують здатність цього лімфатичного новоутворення стискатися і зменшуватися в розмірах в 2 рази. Оскільки ЛМ — це термін, який позначає ваду розвитку лімфатичної системи, ми пропонуємо використовувати саме для набутого лімфатичного утворення (тобто лімфатичного новоутворення) термін «лімфангіома».

KEY WORDS IN UKRAINIAN

Лімфатична мальформація, лімфангіома, лімфатичне новоутворення, шия, ультразвукове дослідження (УЗД), B-режим УЗД, кольорове Допплерівське картування (КДК), кінопетля в УЗД, кіноподібна петля в УЗД, скрипка