December 27, 2017

https://doi.org/10.23999/j.dtomp.2017.34.7

J Diagn Treat Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2017;1:147−55.

Under a Creative Commons license

How to cite this article

Hatab N, Yahya J, Alqulaihi S. Management of alveolar osteitis in dental practice: a literature review. J Diagn Treat Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2017;1:147−55.

Contents: Abstract | Introduction | Review of the Literature | Material and Methods | Results | Discussion | Conclusions | Funding | Conflict Of Interests | Ethical Approval | Patient Consent | Acknowledgements | References (32)

Abstract

Background: Dry socket is one of the most common post-extraction complications with its incidence reaching up to 30% after impacted third molar extractions. In spite of its high incidence, there is no established treatment for the condition.

Objectives: To investigate how efficient different management methods of Alveolar osteitis are, in regards to pain relief, healing process and reduction of the incidence.

Materials and Methods: A literature search of “PubMed-MEDLINE” database was conducted using the keywords “dry socket management,” “alveolar osteitis,” “fibrinolytic alveolitis,” “post-extraction complications.” The inclusion criteria were clinical studies, case reports, reviews and human studies, related to alveolar osteitis published from 2011-2016, written in English language. The exclusion criteria were animal studies, studies that discussed other post-extraction complications, and in any other languages than English.

Results: 63 articles were found and only 31 were reviewed. 18 out of 31 articles were included in the results, after reading the full text, due to lack of significant results in the rest of the articles. Out of these there were 12 clinical studies, 3 systematic reviews and 1 retrospective study.

Conclusion: It was concluded that there is no specific management that could be rated as the best to treat dry socket, due to the lack of evidence to support the use of one management over the other, although there are many options that can help manage it and have proved to be highly effective recently and until today.

Introduction

Dry socket is one of the most common post-extraction complications with its incidence reaching up to 30% after impacted third molar extractions. Many terms can refer to this complication like “fibrinolytic alveolitis”, “localized osteitis”, “alveolitis sicca dolorosa”, “septic socket”, and “necrotic socket” [1]. It has been a topic of discussion in the literature recently, as the main cause and management method haven’t been decided yet.

This study discusses dry socket and focus on the different types of management that have been found in the literature.

Review of the Literature

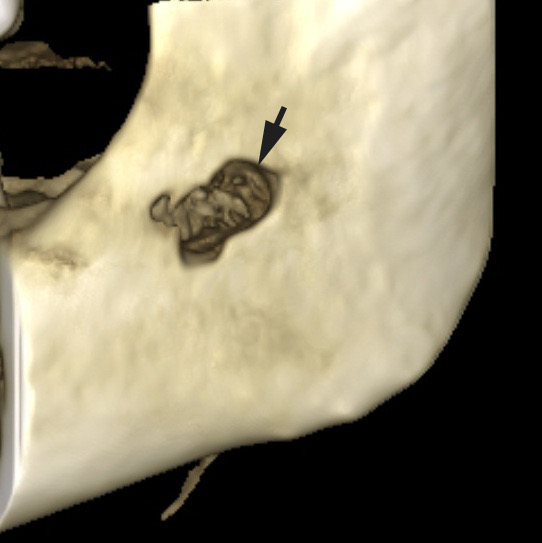

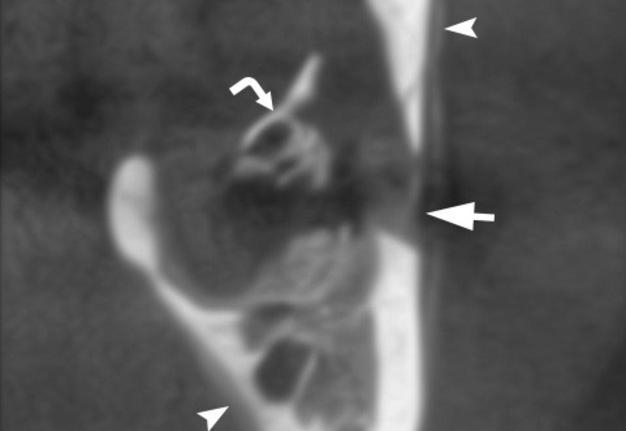

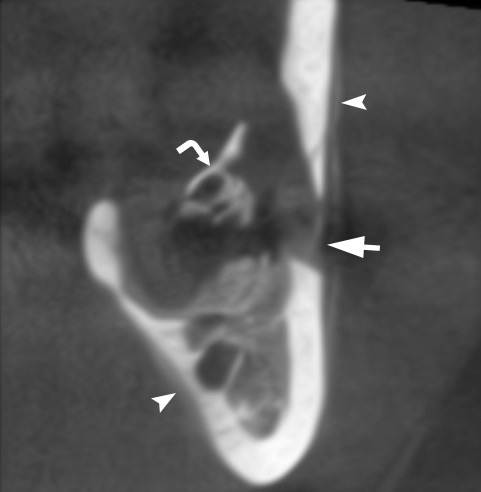

Alveolar osteitis (AO), or dry socket, is a relatively common complication that can occur after tooth extraction. It causes a lot of pain and discomfort but is easily treatable. Its incidence is only 2-5% for normal extractions but can get up to 30% after impacted third molar extractions (Fig 1). Smokers and people with poor oral hygiene are more likely to experience AO after an extraction [2].

The reason behind AO is that the bone and the nerves in the extraction socket stay exposed to air and fluids after the extraction due to dislodgment or disintegration of the blood clot that was previously present inside the socket right after extraction. This causes an infection which can last for multiple days until it is treated. The symptoms of dry socket include pain, halitosis and an unpleasant taste. The halitosis is accompanied by gingival inflammation and ipsilateral regional lymphadenopathy. The pain can be localized or can extend to the temporal region and to the ear (if the dry socket occurs at the third molar region). There are various risk factors for this complication including difficulty of the surgery, age and gender, trauma, irrigation methods, infection and smoking, medical history, systemic disorders, amount of anesthesia, operator’s experience, menstrual cycle and the use of oral contraceptives [3-5].

There are many treatment options for AO including, topical and systemic antibiotics, NSAIDS, antifibrinolytic drugs, avoiding curettage of the socket, relieving the pain by packing a paste of zinc oxide eugenol (ZOE) into the socket and other drug combinations have been used as well. None of the mentioned treatment options has gained universal acceptance or success.

The prevention methods include use of antibiotics, avoiding smoking and the use of mouth rinse and gels, which can help reduce the incidence of AO [5]. This study reviews and discusses on the causes and possible management of alveolar osteitis as a complication after dental extractions which are available in the literature until now.

FIGURE 1A. A 35-year-old lady with alveolar osteitis of the mandible complicated with local osteomyelitis. Alveolar osteitis starts after removal of lower wisdom tooth. 3D reconstructed (A) and coronal (B) CBCT scans shows cortical bone defect (arrow) of the ramus. Also the periosteal reaction (arrowheads) and bone sequester (curved arrow) is noted. On panoramic x-ray the bone resorption (arrow) of the ramus near the postextraction socket (arrowhead) is noted. A sequestrated fragment of the mandibular bone (D) after its removal 8 week after the process starts. (Images of Figure 1 are courtesy of Ievgen I. Fesenko, Assіs Prof; Kyiv, Ukraine)

FIGURE 1B. A 35-year-old lady with alveolar osteitis of the mandible complicated with local osteomyelitis. Alveolar osteitis starts after removal of lower wisdom tooth. 3D reconstructed (A) and coronal (B) CBCT scans shows cortical bone defect (arrow) of the ramus. Also the periosteal reaction (arrowheads) and bone sequester (curved arrow) is noted. On panoramic x-ray the bone resorption (arrow) of the ramus near the postextraction socket (arrowhead) is noted. A sequestrated fragment of the mandibular bone (D) after its removal 8 week after the process starts. (Images of Figure 1 are courtesy of Ievgen I. Fesenko, Assіs Prof; Kyiv, Ukraine)

FIGURE 1C. A 35-year-old lady with alveolar osteitis of the mandible complicated with local osteomyelitis. Alveolar osteitis starts after removal of lower wisdom tooth. 3D reconstructed (A) and coronal (B) CBCT scans shows cortical bone defect (arrow) of the ramus. Also the periosteal reaction (arrowheads) and bone sequester (curved arrow) is noted. On panoramic x-ray the bone resorption (arrow) of the ramus near the postextraction socket (arrowhead) is noted. A sequestrated fragment of the mandibular bone (D) after its removal 8 week after the process starts. (Images of Figure 1 are courtesy of Ievgen I. Fesenko, Assіs Prof; Kyiv, Ukraine)

FIGURE 1D. A 35-year-old lady with alveolar osteitis of the mandible complicated with local osteomyelitis. Alveolar osteitis starts after removal of lower wisdom tooth. 3D reconstructed (A) and coronal (B) CBCT scans shows cortical bone defect (arrow) of the ramus. Also the periosteal reaction (arrowheads) and bone sequester (curved arrow) is noted. On panoramic x-ray the bone resorption (arrow) of the ramus near the postextraction socket (arrowhead) is noted. A sequestrated fragment of the mandibular bone (D) after its removal 8 week after the process starts. (Images of Figure 1 are courtesy of Ievgen I. Fesenko, Assіs Prof; Kyiv, Ukraine)

Material and Methods

In this study, a literature search of “PubMed-MEDLINE” database was conducted with the following search terms “dry socket management”, “alveolar osteitis”, “fibrinolytic alveolitis”, “post-extraction complications”. The terms were also merged using the word “AND” to find results that contained two or more of the keywords.

The inclusion criteria were clinical studies, case reports, reviews and human studies, related to alveolar osteitis published from 2011─2016, written in English language.

The exclusion criteria were animal studies, studies that discussed other post-extraction complications, and in any other languages than English.

The selection of articles was based on reading the titles and the abstract in order to identify the relevance of the contents of the articles.

Results

In this study, 63 articles were found using the keywords, and after applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria only 31 were reviewed. 18 out of 31 articles were included in the results, after reading the full text, due to lack of significant results in the rest of the articles.

Out of these there were 12 clinical studies, 3 systematic reviews and 1 retrospective study. The studies included were divided according to the level of pain, healing process, reduction of the incidence of AO and reduction in the inflammation and swelling.

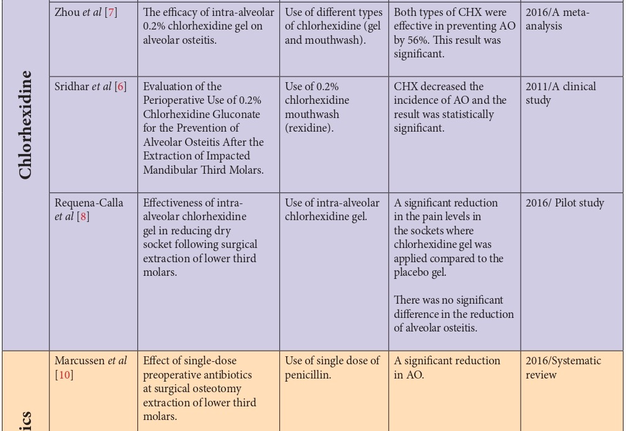

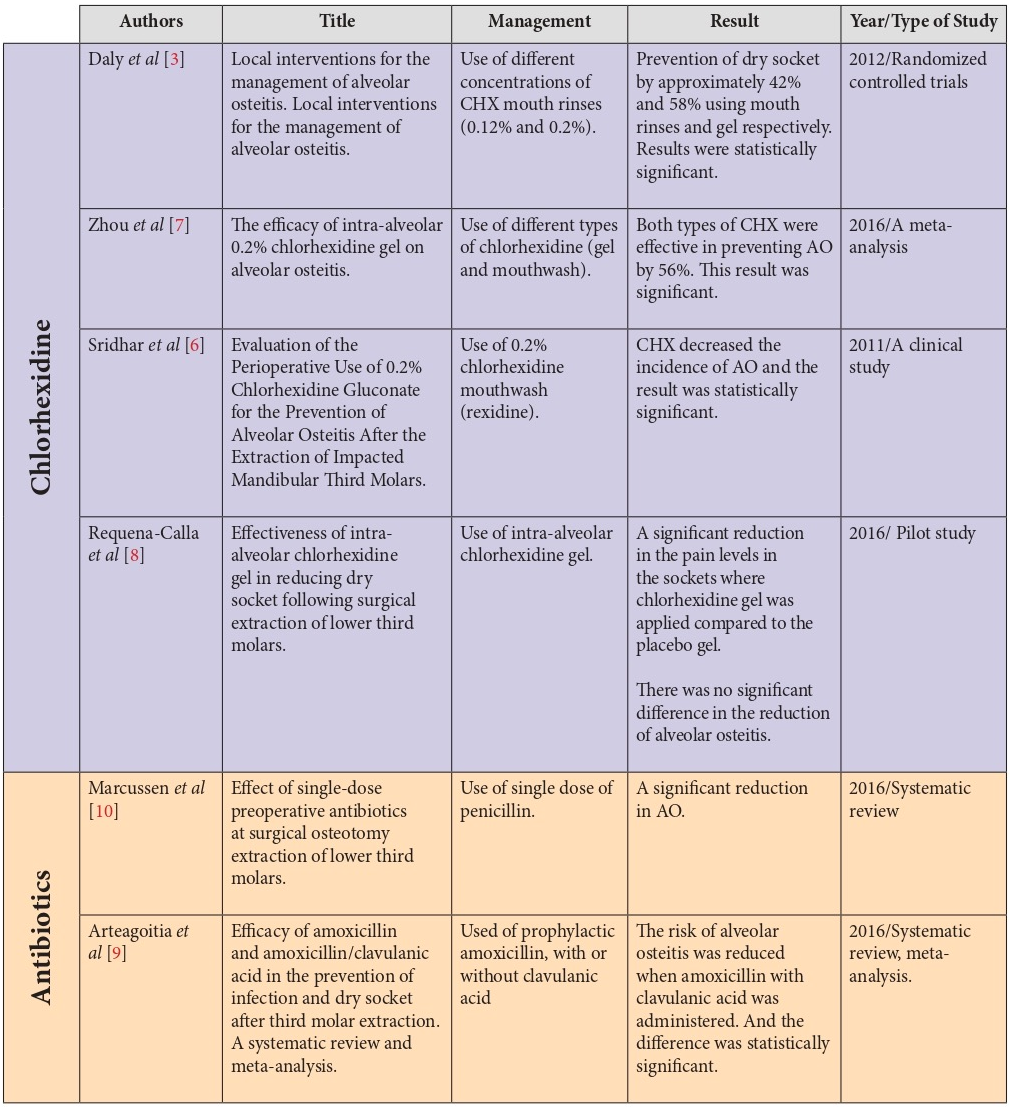

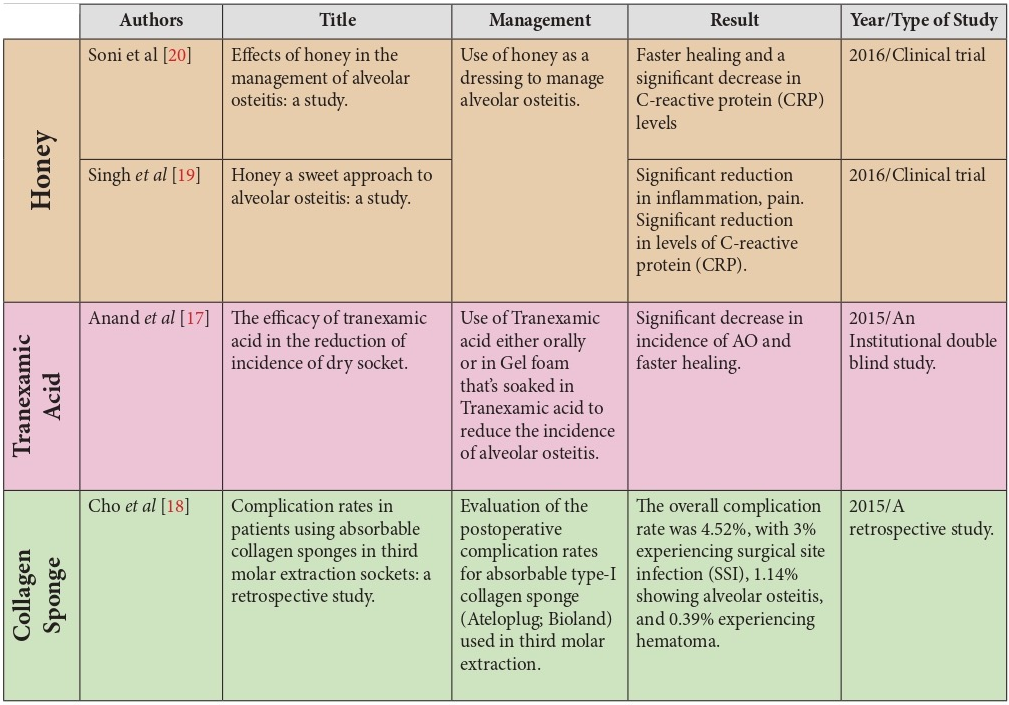

In attempting to find the management that can reduce the incidence of AO, it was found that many options were available including CHX (chlorhexidine), which works as an antibacterial and an antiseptic in the socket, antibiotics like Penicillin V and amoxicillin with clavulanic acid, PRF (platelet rich firbrin) and PRP (platelet rich plasma), PRGF (plasma rich in growth factors), ozone gas, tranexamic acid, and the use of collagen sponge.

The management options that were found to be successful at reducing the levels of pain were the use of CHX, alvogyl, PRF and PRP, PRGF, LLLT (low level laser therapy), honey and zinc oxide eugenol.

Accelerated healing was achieved by the use of PRF and PRP, PRGF, honey and Tranexamic acid. Honey also reduced the inflammation and the C-reactive protein levels in the sockets. PRF and PRP reduced the swelling.

Discussion

Each one of the mentioned articles discussed different management options for alveolar osteitis. About 4 reviews discussed the use of different types of Chlorhexidine (CHX) as a management option. CHX is antiseptic and antimicrobial, it reduces the oral microbes in the wound and plays a primary role in stopping fibrinolysis by killing the bacteria that causes it [6]. Daly et al [3] studied the difference between CHX mouth rinses with different concentrations of 0.12% and 0.2%, and CHX gel with 0.2% concentration. These groups were compared with a placebo group. It was found that rinsing with CHX mouth rinses both before and after the extractions prevented about 42% of alveolar osteitis when compared to the placebo group. There was no significant difference in the results when both the concentrations of the mouth rinses (0.12% and 0.2%) were compared. It was also found that placing 0.2% CHX gel in the sockets after extractions prevented about 58% of alveolar osteitis compared to the placebo group [3].

Zhou et al [7] assessed the effect of 0.2% CHX gel in the prevention of dry socket, where it was established that the gel reduced the risk of dry socket by 56% compared to the placebo group. However, there was no significant difference between 0.2% CHX gel and 0.12% CHX mouthwash.

Sridhar et al [6] evaluated the perioperative use of 0.2% CHX gluconate as a preventive method for alveolar osteitis. The reduction of the complication was statistically significant, as there was no case of alveolar osteitis when CHX was used 1 day before and 7 days after the surgery, twice daily. However, Requena-Calla et al [8] found that there was no relationship between the type of gel that is administered intra-alveolarly and the incidence of alveolar osteitis, but there was a significant reduction in the pain levels in the sockets where chlorhexidine gel was applied compared to the placebo gel.

Antibiotics also kill and inhibit the growth of bacteria due to the antimicrobial and antibacterial properties, therefore they inhibit fibrinolysis and reduce the incidence of dry socket [9, 10]. Marcussen et al [10] reviewed the effect of single-dose antibiotics on surgical extractions where it was found that a single dose of penicillin V 0.8g administered before the surgical osteotomy extraction significantly reduced the incidence of alveolar osteitis.

Arteagoitia et al [9] assessed the use of amoxicillin with or without clavulanic acid in the prevention of dry socket after extractions and concluded that the combination of amoxicillin with clavulanic acid reduced the risk of the complication significantly compared to amoxicillin on its own.

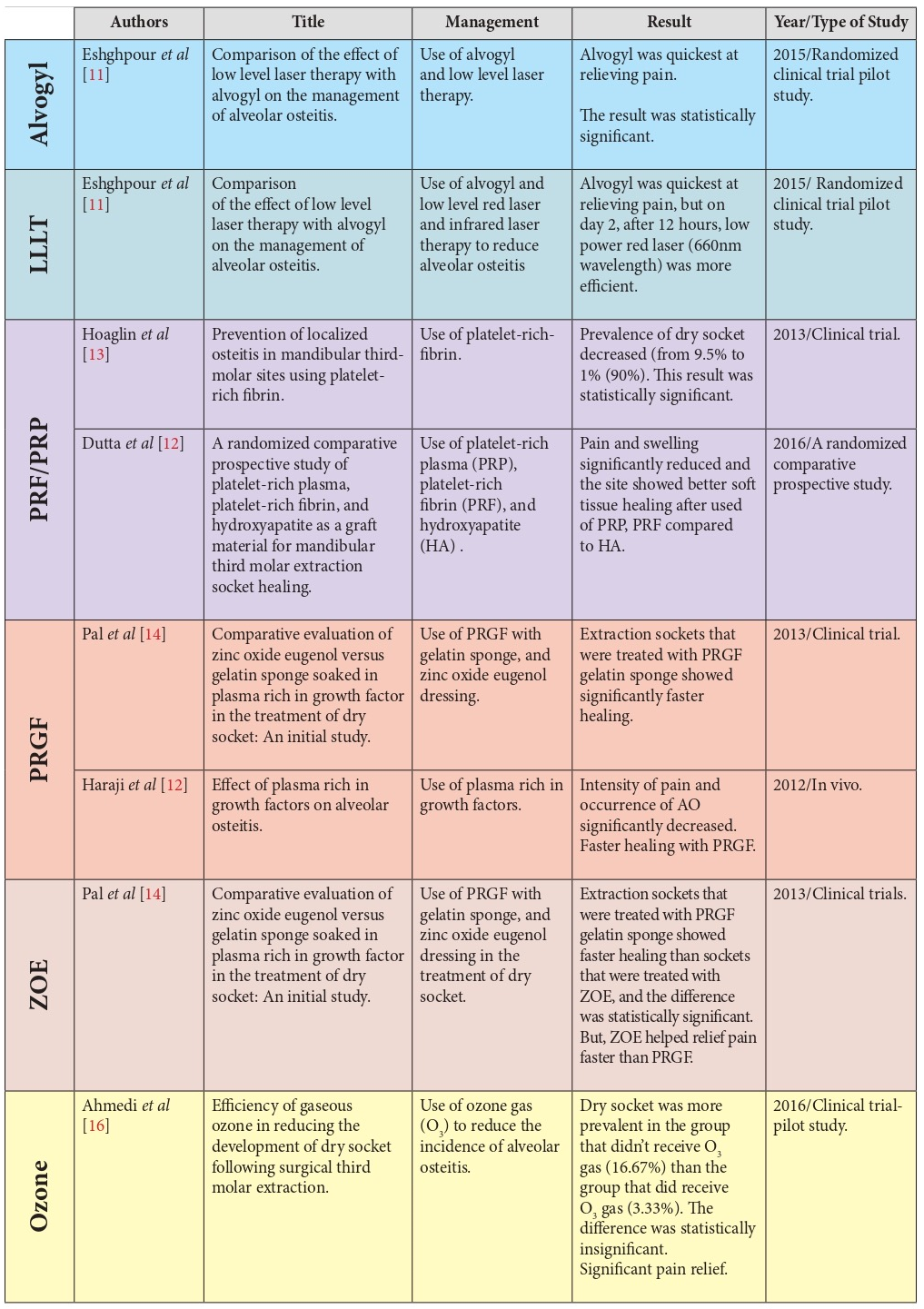

Alvogyl and laser therapy are also included in the treatment options for alveolar osteitis. Alvogyl contains eugenol which acts as an analgesic, iodoform which acts as an antimicrobial and butamben which acts as an anesthetic [11]. The laser has antimicrobial features and it also increases the speed and quality of wound healing [11]. Eshghpour et al [11] compared the effects of both these options to manage the complication. He found that alvogyl helped relief pain the quickest compared to the low power red laser (660nm wavelength), but on day 2 and after 12 hours, low power red laser was more efficient than alvogyl. Low level infrared laser (810nm wavelength) did not show any better results than both alvogyl and low power red laser.

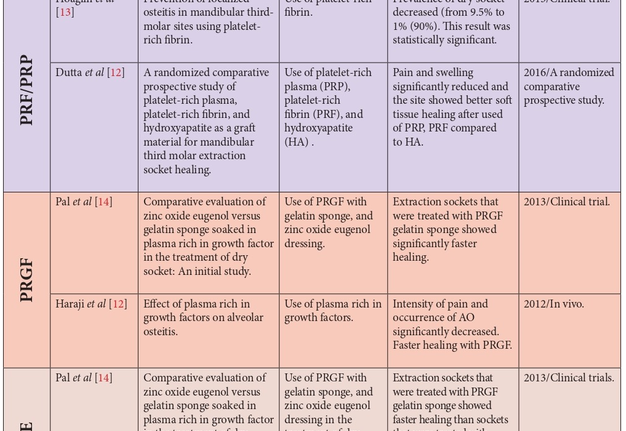

Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) and platelet-rich plasma (PRP) are also one of the management options. They act as bone grafting materials, which help in bone repair by stimulating mitogenic responses in the periosteum. They can also prevent foreign body inflammatory reactions [12, 1]. Hoaglin et al [13] used platelet-rich fibrin to treat localized osteitis in the sockets after extractions and as a result there was better healing and clot retention in the sockets and it greatly reduced the post-operative management time. PRF caused 90% reduction in the prevalence of alveolar osteitis. Dutta et al [12] compared the use of PRF, PRP and hydroxyapatite (HA) in the management of dry socket and found that there was significant reduction of pain and swelling and also better soft tissue healing when PRF and PRP were used, compared to HA.

Plasma rich in growth factors (PRGF) and zinc oxide eugenol (ZOE) can be used as a treatment option for dry socket. PRGF contains platelets, fibrinogen and growth factors like PDGF, TGF, PDEGF, PDAF, IGF-1 and PF-4, these factors increase angiogenesis, chemotaxis of macrophages and fibroblasts and therefore increase vascularity. They also enhance osteogenesis by increasing granulation tissue production and epithelialization. It is biocompatible and can also have antimicrobial features. ZOE has antiseptic and anesthetic properties as it depresses sensory receptors involved in pain perception [14]. Pal US et al [14] compared both of these treatments in a study and the result was that the use of PRGF resulted in better tissue healing than ZOE, but ZOE was faster in relieving pain. When compared to each other, the differences were statistically significant. Haraji et al [15] assessed the preventive effect of PRGF on alveolar osteitis (AO) and concluded that there was a significant reduction in AO occurrence and pain, and accelerated healing of the sockets.

Ozone gas is also effective in reducing the occurrence of AO. It has antibacterial features as it has the ability to form oxidizing free radicals and destroy the membranes and cell walls of bacteria. In addition, O3 gas helps in synthesis of leukotrienes, interleukins and prostaglandins, which gives it anti-inflammatory properties. It can also improve delivery of oxygen to hypoxic tissues by stimulating oxygen metabolism [16]. Ahmedi et al [16] studied the efficacy of O3 gas and found that there was a significant reduction in inflammation, pain levels, post-operative recovery period, and there was also improved tissue healing. But there was no significant reduction in the occurrence of AO.

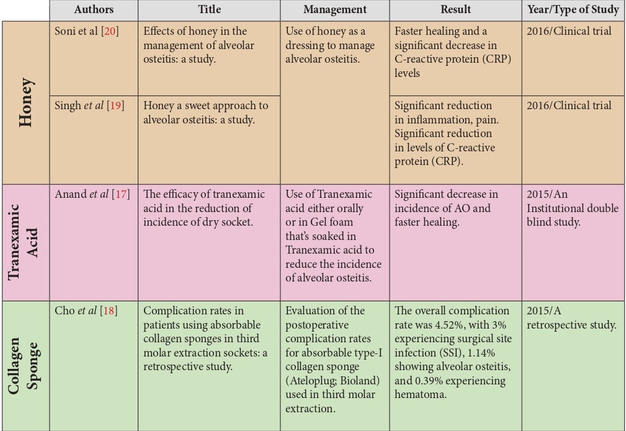

Tranexamic acid is an antifibrinolytic as it prevents the attachment of plasminogen and plasmin and therefore prevents the degradation of fibrin. Anand et al [17] evaluated the efficacy of Tranexamic acid either systemically or locally as a gel foam in comparison with a placebo, he concluded that there was a significant decrease in the incidence of AO and there was faster tissue healing in comparison with the placebo group. There was no difference between the local or systemic administration of the medicament.

Cho et al [18] suggested that the use of absorbable type-1 collagen sponge reduced the risk of AO but the result was not statistically significant. Type-1 collagen is a fibrillar collagen which supports bone matrix. It enhances hemostasis, facilitates granulation tissue formation, and protects the wound surface.

Recently, Soni et al [20] and Singh et al [19] evaluated the effects of honey as a dressing as a management option for AO. Honey is hyperosmolar and due to that it can reduce the edema. it forms a physical barrier, keeps moist environment and prevent bacterial colonization due to its viscous property. It is also bactericidal due to its low PH and the hydrogen peroxide content. Due to its high nutrient content, it promotes rapid epithelialization. As a result, honey significantly reduced C-reactive protein levels and thus reduced inflammation and pain, it also helped in accelerated tissue healing.

According to all the results that we reviewed, the percentages of success were better when substances that accelerated the healing process and regeneration of the bone were used like PRGF and PRF (90% reduction rate), in comparison with the substances that acted as antibacterials and antimicrobials like CHX (ranging from 42% to 58% being the maximum reduction rate). This is due to the fact that the main cause of AO is not from bacterial origin. Therefore we can say that the best results would be achieved if both those management options were used together at the same time.

Conclusion

In this study, and according to the literature [1-32], it was concluded that there is no specific management that could be rated as the best to treat dry socket, due to the lack of evidence to support the use of one management over the other, although there are many options that can help manage it and have proved to be highly effective recently and until today. Further investigations on larger samples need to be done in order to reach the main cause and the best management for AO. However, the primary aim of a practitioner in a dental clinic is to relief pain, reduce post-operative time and promote healing to preserve the socket.

Funding

None.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Role of Author and Co-authors

Nur Hatab (concept of the paper and editing)

Jenan Yahya (material collection and writing)

Sara Alqulaihi (material collection and writing)

Ethical approval

Approval was obtained from the Medical Ethics Committee of the RAK Medical and Health Sciences University.

Patient Consent

No needed.

Acknowledgements

None.

REFERENCES

-

Kolokythas A, Olech E, Miloro M. Alveolar osteitis: a comprehensive review of concepts and controversies. Int J Dent 2010:249073. Crossref.

-

Bowe DC, Rogers S, Stassen LF. The management of dry socket/alveolar osteitis. J Ir Dent Assoc 2011;57(6):305–10.

-

Daly B, Sharif MO, Newton T, Jones K, Worthington HV. Local interventions for the management of alveolar osteitis (dry socket). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;12:CD006968. Crossref

-

Eshghpour M, Nejat AH. Dry socket following surgical removal of impacted third molar in an Iranian population: incidence and risk factors. Niger J Clin Pract 2013;6(4):496–500.

-

Tarakji B, Saleh LA, Umair A, Azzeghaiby SN, Hanouneh S. Systemic review of dry socket: aetiology, treatment, and prevention. J Clin Diagn Res 2015;9(4):ze10–3.

-

Sridhar V, Wali GG, Shyla HN. Evaluation of the perioperative use of 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate for the prevention of alveolar osteitis after the extraction of impacted mandibular third molars: a clinical study. J Maxillofac Oral Surg 2011;10(2):101–11.

-

Zhou J, Hu B, Liu Y, Yang Z, Song J. The efficacy of intra-alveolar 0.2% chlorhexidine gel on alveolar osteitis: a meta-analysis. Oral Dis 2017;23(5):598–608.

-

Requena-Calla S, Funes-Rumiche I. Effectiveness of intra-alveolar chlorhexidine gel in reducing dry socket following surgical extraction of lower third molars. A pilot study. J Clin Exp Dent 2016;8(2):e160–3.

-

Arteagoitia M-I, Barbier L, Santamaría J, Santamaría G, Ramos E. Efficacy of amoxicillin and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid in the prevention of infection and dry socket after third molar extraction. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2016;21(4):e494–e504.

-

Marcussen KB, Laulund AS, Jorgensen HL, Pinholt EM. A systematic review on effect of single-dose preoperative antibiotics at surgical osteotomy extraction of lower third molars. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2016;74(4):693–703. Medline

-

Eshghpour M, Ahrari F, Najjarkar N-T, Khajavi M-A. Comparison of the effect of low level laser therapy with alvogyl on the management of alveolar osteitis. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2015;20(3):e386–92.

-

Dutta SR, Passi D, Singh P, Sharma S, Singh M, Srivastava D. A randomized comparative prospective study of platelet-rich plasma, platelet-rich fibrin, and hydroxyapatite as a graft material for mandibular third molar extraction socket healing. Natl J Maxillofac Surg 2016;7(1):45–51.

-

Hoaglin DR, Lines GK. Prevention of localized osteitis in mandibular third-molar sites using platelet-rich fibrin. Int J Dent 2013:875380. Crossref

-

Pal US, Singh BP, Verma V. Comparative evaluation of zinc oxide eugenol versus gelatin sponge soaked in plasma rich in growth factor in the treatment of dry socket: an initial study. Contemp Clin Dent 2013;4(1):37–41.

-

Haraji A, Lassemi E, Motamedi MH, Alavi M, Adibnejad S. Effect of plasma rich in growth factors on alveolar osteitis. Natl J Maxillofac Surg 2012;3(1):38–41.

-

Ahmedi J, Ahmedi E, Sejfija O, Agani Z, Hamiti V. Efficiency of gaseous ozone in reducing the development of dry socket following surgical third molar extraction. Eur J Dent 2016;10(3), 381–5.

-

Anand KP, Patro S, Mohapatra A, Mishra S. The efficacy of tranexamic acid in the reduction of incidence of dry socket: an institutional double blind study. J Clin Diagn Res 2015; 9(9):ZC25–8. Medline

-

Cho H, Jung H-D, Kim B-J, Kim C-H, Jung, Y-S. Complication rates in patients using absorbable collagen sponges in third molar extraction sockets: a retrospective study. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg 2015;41(1):26–9.

-

Singh V, Pal US, Singh R, Soni N. Honey a sweet approach to alveolar osteitis: A study. Natl J Maxillofac Surg 2014;5(1):31–4.

-

Soni N, Singh V, Mohammad S, Singh RK, Pal US, Singh R, Pal M. Effects of honey in the management of alveolar osteitis: a study. Natl J Maxillofac Surg 2016;7(2):136–47.

-

Summers A. Emergency management of alveolar osteitis. Emerg Nurse 2011; 19(8):28–30.

-

Taberner-Vallverdú M, Nazir M, Sánchez-Garcés MÁ, Gay-Escoda C. Efficacy of different methods used for dry socket management: a systematic review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2015;20(5):e633–9.

-

Yengopal S, Mickenautsch S. Chlorhexidine for the prevention of alveolar osteitis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2012;41(10):1253–64.

-

Sharif MO, Dawoud BE, Tsichlaki A, Yates JM. Interventions for the prevention of dry socket: an evidence-based update. Br Dent J 2014;217(1):27–30.

-

Ramos E, Santamaría J, Santamaría G, Barbier L, Arteagoitia I. Do systemic antibiotics prevent dry socket and infection after third molar extraction? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2016;122(4):403–25.

-

Rakhshan V. Common risk factors for postoperative pain following the extraction of wisdom teeth. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg 2015;41(2):59–65.

-

Motamedi MRK. To irrigate or not to irrigate: immediate postextraction socket irrigation and alveolar osteitis. Dent Res Journal (Ishafan) 2015;12(3):289–90.

-

Akinbami BO, Godspower T. Dry socket: incidence, clinical features, and predisposing factors. Int J Dent 2014:796102. Crossref

-

Tymofieiev OO, Ushko NO, Tymofieiev OO, Yarifa MO, Fesenko IeI. Prevention of inflammatory complications upon surgeries in maxillofacial region. J Diagn Treat Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2017;1:105−12.

-

Barona-Dorado C, González-Regueiro I, Martín-Ares M, Arias-Irimia O, Martínez-González JM. Efficacy of platelet-rich plasma applied to postextraction retained lower third molar alveoli. A systematic review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2014;19(2):e142–8.

-

Hatab N, Patel T, Bakkour A. The efficiency of rhBMP-7 in oral and maxillofacial bone defects: a systematic review. J Diagn Treat Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2017;1:77−88.

-

Rodríguez-Pérez M, Bravo-Pérez M, Sánchez-López JD, Muñoz-Soto E, Romero-Olid MN, Baca-García P. Effectiveness of 1% versus 0.2% chlorhexidine gels in reducing alveolar osteitis from mandibular third molar surgery: a randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2013;18(4):e693–e700.