Patient-specific Prosthetic Appliance for Interim Management of Chronic Orocutaneous Fistula in the Irradiated and Vessel-depleted Head and Neck Patient – A Case Report and Technical Note

December 3, 2022

J Diagn Treat Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2022;6: 148–57.

Under a Creative Commons license

HOW TO CITE THIS ARTICLE

Le JM, Murdock K, Kase MT. Patient-specific prosthetic appliance for interim management of chronic orocutaneous fistula in the irradiated and vessel-depleted head and neck patient – a case report and technical note. J Diagn Treat Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2022;6(12):148–57. https://doi.org/10.23999/j.dtomp.2022.12.1

NATIONAL REPOSITORY OF ACADEMIC TEXTS

https://nrat.ukrintei.ua/en/searchdoc/2022U000201/

ABSTRACT

The formation and persistence of an orocutaneous fistula as a sequela of major head and neck surgery followed by microvascular reconstructive surgery and adjuvant radiation therapy is a common and frustrating challenge to address. When reconstructive surgical options are exhausted, limited, or with high risk for failure, the fabrication of an oral appliance can provide a temporary to long-term treatment option for the patient. In this case report, an oral appliance was fabricated to decrease salivary incontinence, improve intelligibility, and deglutition in a 60-year-old patient who underwent a subtotal glossectomy with radical mandibulectomy followed by reconstruction with an osteocutaneous radial forearm free flap who developed a chronic orocutaneous fistula following completion of radiation therapy.

INTRODUCTION

Chronic orocutaneous fistula formation in conjunction with hardware exposure is not an uncommon complication, occurring 9-11% following major head and neck surgery.1,2 However, it can be a burdensome challenge for the reconstructive surgeon when the wound has been irradiated and chronically inflamed. Often, this can be treated using local or regional soft tissue flaps to create a barrier and seal the oral cavity from the skin and external environment. However, in an irradiated wound bed that is poorly vascularized and fibrotic, soft tissue mobility may be limited and a vascularized free tissue transfer may be necessary to provide healthy vascularized tissue bulk to obturate the fistula. Unfortunately, the utility of microvascular free tissue transfer can be limited in a vessel-depleted neck. In this case report, we demonstrate the utility of a prosthetic appliance as a nonsurgical option in managing a chronic orocutaneous fistula with exposed hardware and bone in the irradiated and vessel-depleted neck.

The use of an orofacial prosthetic appliance for the management of an orocutaneous fistula is limited but has been described in the literature. For example, a case report in 1994 described the use of a silastic foam dressing to obturate a large orocutaneous fistula for end-stage malignant head and neck disease.3 In this case, the large dressing was held in place by an orthodontic headgear and helped improved the quality of remaining life for the patient. In another case report in 2002, a silicone-based material (vinyl polysiloxane) was used as interim obturator for a chronic orocutaneous fistula prior to definitive vascularized soft tissue reconstruction within a month period.4 In this case, the obturator served to better control the salivary incontinence; thus, resulting in decreased wound dressing changes. In 2007, a case report described an intraoral-only acrylic resin device fabricated to serve the sole purpose of preventing salivary incontinence via obturation without an extraoral component.5 All the formerly described methods are adequate treatment options to address one or more of the following issues: salivary incontinence, poor quality of life, or poor wound healing for a short period of time (less than 1 month). To take it a step further, we describe a similar prosthetic option that will not only reduce salivary incontinence and improve quality of life, but also improve deglutition and articulation. In this article, we describe a case where vascularized free tissue transfer was not an option and surgical debridement with local flaps would be too risky due to prior radiation therapy. Therefore, the patient received an intraoral mandibular prosthetic appliance that was fitted to seal the orocutaneous fistula tract, provide the necessary volume to articulate with the palate, and improve deglutition. This ultimately decreased the amount of salivary incontinence and made the patient more intelligible to the public.

CASE PRESENTATION

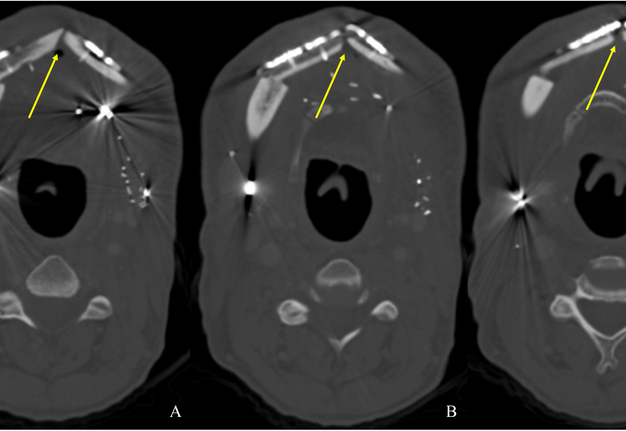

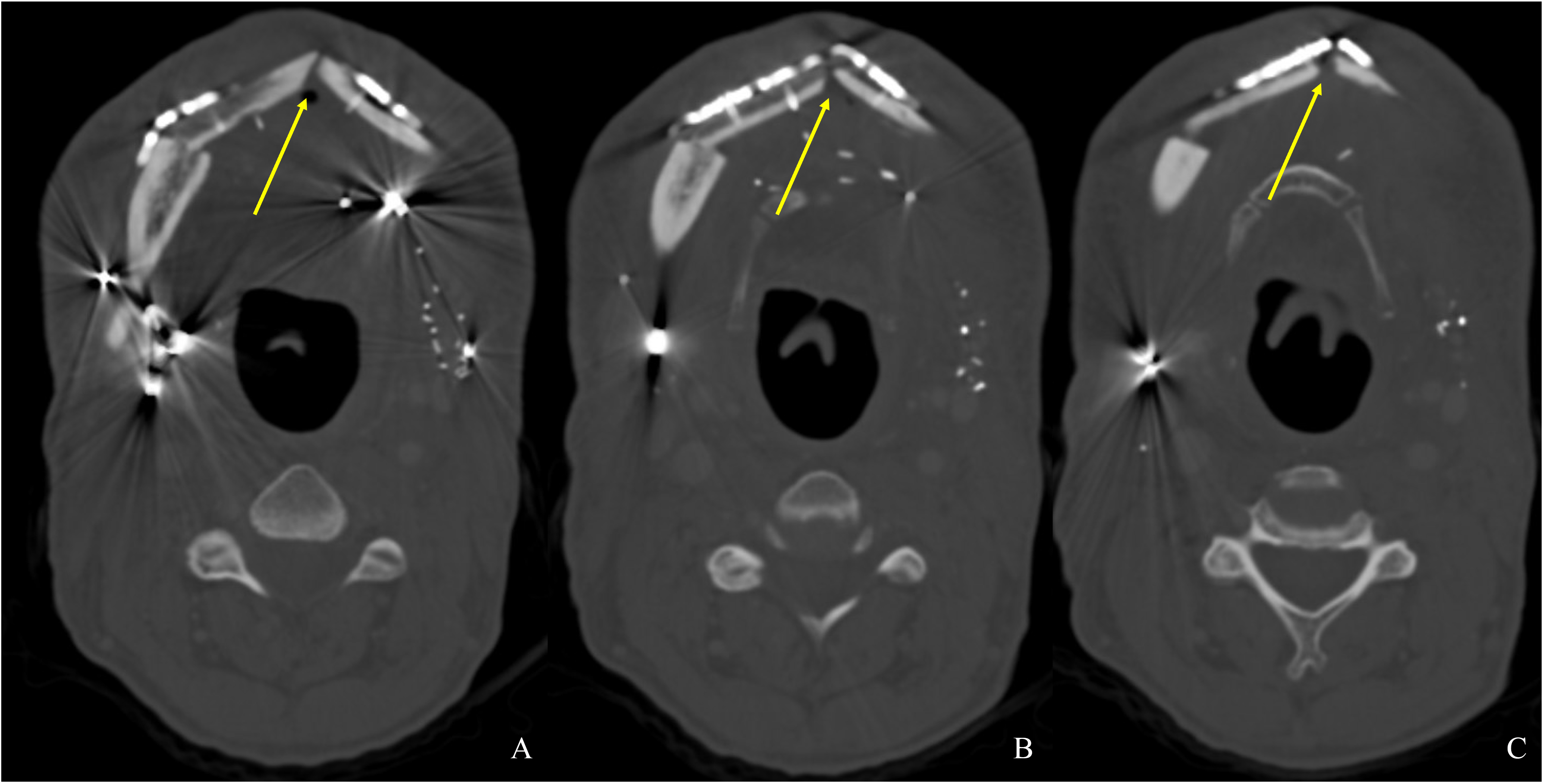

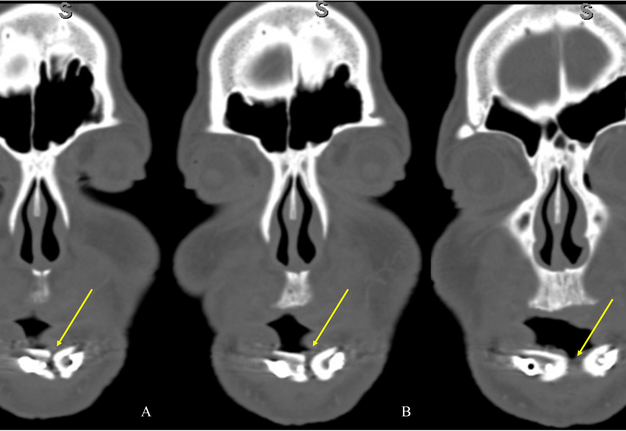

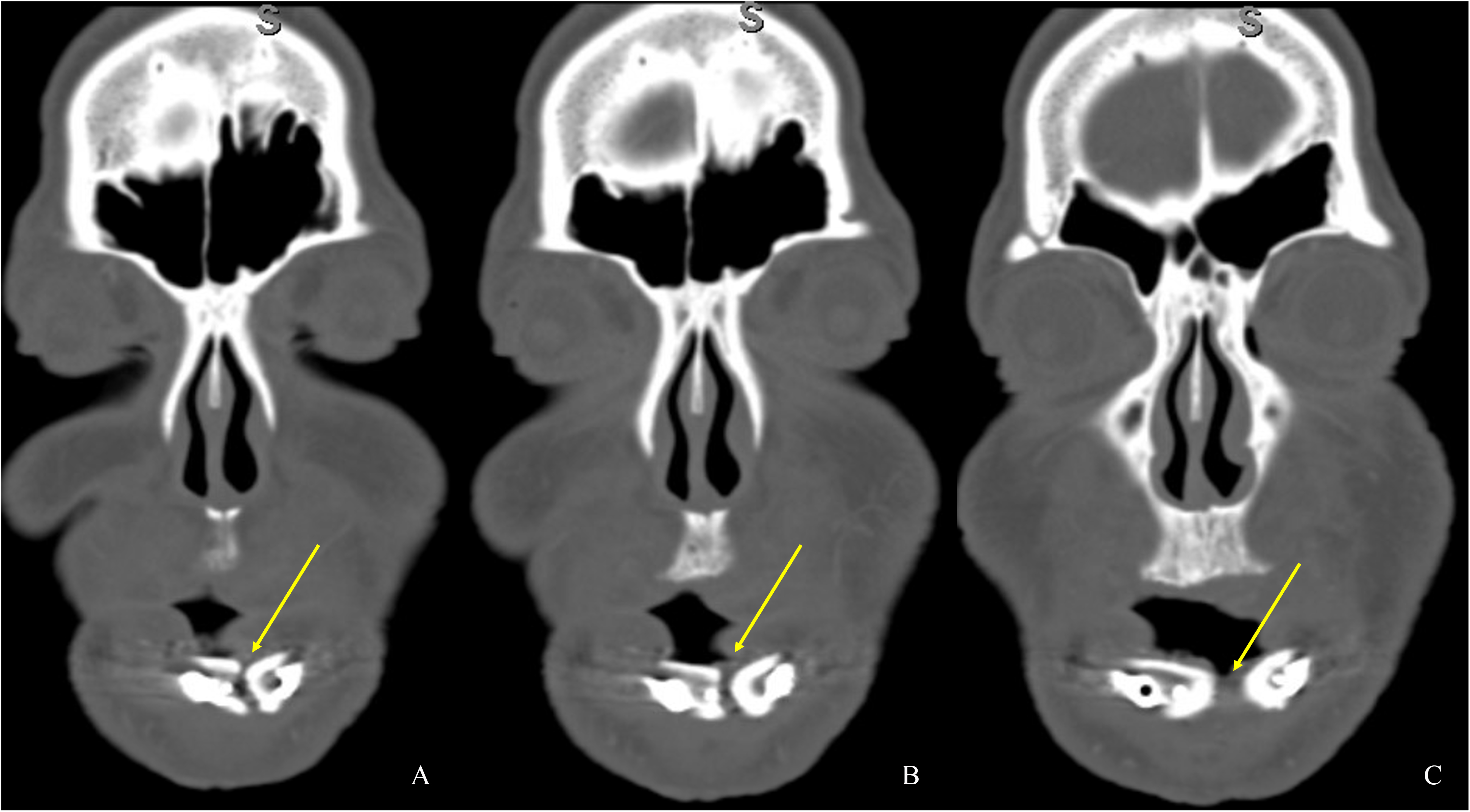

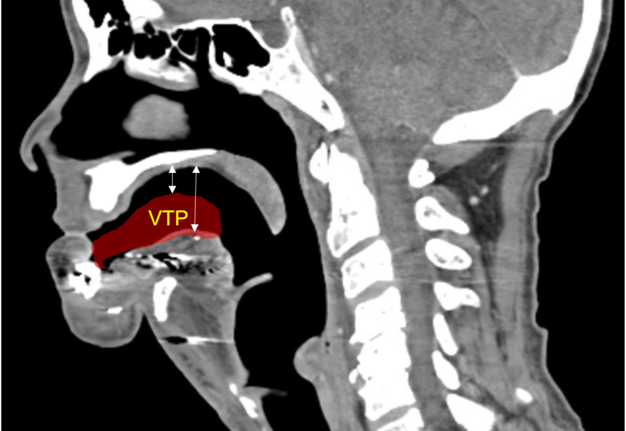

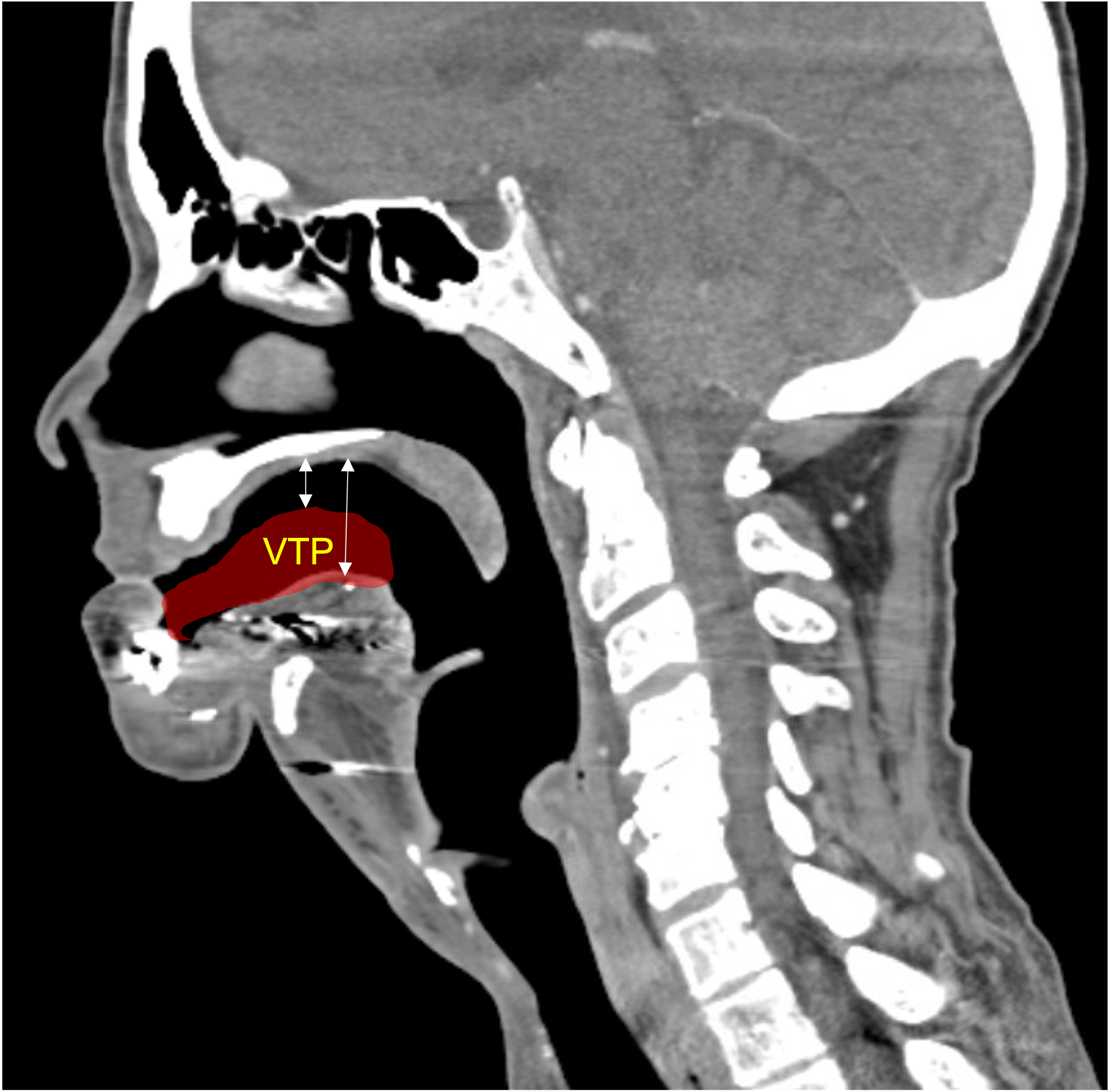

A 60-year-old male with a history of pT4aN3M0 squamous cell carcinoma of the oral tongue treated with a subtotal glossectomy, composite mandibulectomy, bilateral neck dissections, and reconstruction with an osteocutaneous radial forearm free flap followed by adjuvant chemoradiotherapy presented to our clinic for evaluation for an oral prosthesis to manage a chronic orocutaneous fistula tract in the setting of osteoradionecrosis (ORN) and exposed hardware. The patient was edentulous, feeding tube dependent, had constant jaw pain and persistent salivary incontinence which created a poor healing wound bed around the exposed hardware and radial bone (Figs 1 and 2). The patient was started on the PENTOCLO protocol (Pentoxifylline 400mg twice daily, Vitamin E 1000 IU once daily, Clodronate 1.6g once daily, and Chlorhexidine 0.12% twice daily) for ORN and the reconstruction options were discussed at a multidisciplinary conference. Based on computed tomography (CT) imaging studies, a microvascular free flap transfer was not an option due to the absence of available recipient vessels in the neck for anastomosis. CT imaging demonstrating nonunion at the anterior segments of the neomandible associated with exposure shown in Figures 3 and 4. As a result, the treatment options included: 1) Aggressive wound debridement and placement of an allograft, followed by primary closure versus local intraoral flap, or nasolabial flap, 2) Partial removal of a section of the exposed hardware and bone, or 3) Prosthetic appliance to obturate the fistula, decrease the salivary incontinence and assist with wound healing for option 1 or 2. After the treatment options were discussed with the patient, he opted for the prosthetic appliance.

Prosthetic Treatment

The patient presented to the Maxillofacial Prosthodontic clinic at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) with severe trismus related to his prior procedures. Fabrication of a maxillary complete denture in addition to a mandibular prosthetic appliance was impossible due to the limited available restorative space. Therefore, only a combination tongue and mandibular obturator prosthesis was fabricated out of orthoresin (Ortho-Jet by Patterson Dental, St. Paul, Minnesota, USA) for the patient to aid in speech, deglutition and intraoral obturation of the acquired mandibular defect. This was accomplished by making a mandibular alginate impression and fabrication of subsequent diagnostic cast. From the diagnostic cast a custom impression tray was fabricated. The impression tray was border molded with green stick impression compound ensuring adequate fit into the mandibular defect and an impression of the floor of the mouth and remaining mandibular arch form was made with medium volume polyvinylsiloxane impression material. The resulting master cast was used to fabricate a processed clear resin mandibular obturator record base with combined prosthetic tongue. The cameo surface of the prosthesis was lined with tissue conditioner (COE-COMFORT™ by GC Corporation Inc.©, Tokyo, Japan) and the patient was guided through phonetic movements during the set time of the tissue conditioner. Excess material was trimmed and removed from the prosthesis prior to permitting the patient to function with the prosthesis in place for 10 days. He then returned to the clinic for conversion of the prosthesis from COE-COMFORT™ to orthoresin. At this time the patient reported difficulty manipulating the prosthesis to and from his mouth, so a 0.036-inch orthodontic retainer wire handle was added to the device anteriorly for ease of insertion and removal (Figs 5–7). Following the final fabrication and placement of the appliance, immediate improvement in salivary incontinence and articulation was noted (Figs 8 and 9). The patient also reported improved deglutition at the next follow up visit. The decision to monitor the extraoral fistula at this time was made as opposed to fabrication of a facial plug prosthesis based on difficulty in engaging undercuts at the extraoral defect site around the exposed necrotic bone and unstable changing wound architecture.

DISCUSSION

The development of chronic orocutaneous fistula following major head and neck reconstructive surgery is not an uncommon complication encountered by the surgeon.1,2,6 The incidence can be even higher in patients exposed to radiation therapy.7 Salivary incontinence is not only a burdensome problem for the patient, but also creates a contaminated wound that leads to breakdown/dehiscence and hardware or bone exposure that can compromise the surgical reconstruction.

Common treatment goals for the management of orocutaneous fistulas include the excision of the fistula tract followed by debridement of necrotic or infected tissue, and a water-tight wound closure to create a barrier from the intraoral and extraoral environment. Reconstructive surgical options are often planned according to the reconstructive ladder concept based on the location and size of the wound bed. Often, local soft tissue advancement is sufficient in treating small fistulas. However, when the fistula is associated with a large wound associated with hardware and bone, a more complex local and/or regional soft tissue flap may be indicated. This treatment often includes but is not limited to the debridement of the infected or necrotic soft and hard tissue, and removal of the affected hardware. Furthermore, in cases where a large volume of hard and soft tissue is removed, a regional and/or microvascular free tissue transfer may be indicated to obturate the defect and provide healthy vascularized tissue bulk to promote wound healing.8,9

Furthermore, each reconstructive treatment option is limited by a multitude of patient-specific factors that include prior radiation therapy, behavioral practices (e.g., tobacco smoking), and medical comorbidities (e.g., anemia, poor glycemic control, and malnutrition).10–12 Common side effects following radiation therapy include fibrosis and poor vascularization of the wound bed.13 As a result, the amount of soft tissue elasticity for advancement and revascularization is limited. In addition, tobacco smoking has been shown to be associated with delayed healing and wound dehiscence in the surgical patient.14 Finally, malnutrition, such as low albumin levels, has been shown to be associated with increased incidence perioperative complications following microvascular reconstructive surgery of the head and neck.15,16

In this patients’ case, fabrication of a combined tongue and mandibular obturator prosthesis was selected for numerous reasons. The patient desired a solution that would not require additional surgery, alleviate salivary incontinence, obturate the intraoral defect, as well as aid in speech and deglutition. A multidisciplinary approach to treating complex patients with these types of defects most commonly includes reconstructive surgery, maxillofacial prosthodontics, speech pathology, and anaplastology.17

The tongue is an essential organ for a patient to perform the basic functions of speech and deglutition. The excision of a portion or the entirety of the tongue creates significant limitations for these patients. Traditionally maxillofacial prosthetic management of patients who undergo partial glossectomies are rehabilitated with a palatal augmentation prosthesis; however, patients who undergo total glossectomies are rehabilitated with a mandibular tongue prosthesis.18 Aponte-Wesson et al (2022) described fabrication of a silicone tongue prosthesis, which increased a patients speech intelligibility from 44% to 80%, decreased signs of aspiration and oral residue after swallowing and greatly improved the patients’ quality of life.17 A prosthetic tongue helps to modulate vocal frequencies in the oral cavity, much like the natural tongue does. Rehabilitation with a tongue prosthesis also allows patients to improve dietary intake by aiding in directing a food bolus posteriorly into the esophagus.18 The prosthesis provides the volume and decreases the distance between the residual tongue and/or floor of mouth; thus, allowing contact with the palate upon activation of the remaining oral musculature (Fig 10). In this case a combined tongue and mandibular obturator prosthesis was fabricated which was able to address and improve our patients’ expectations.

Although the decision was made to monitor and not address the extraoral component of the patient’s defect at this time, prosthetic rehabilitation of orofacial fistulas have been described in the literature and shown to be successful in sealing the oral cavity from the extraoral environment. Kumar et al (2008) described the treatment for an orofacial fistula with an acrylic facial plug prosthesis relined with soft liner to provide an adequate seal during function and secured with circumferential head straps.19 In our case, once the extraoral soft tissue architecture is more stable in the future, the decision to fabricate a facial prosthetic component will be considered. The patient has been monitored for 5 months since the delivery of the prosthesis without any need for adjustments. There has been a progressive clinical improvement in the soft tissue since the placement of the prosthesis as well.

CONCLUSION

In this article, we described an acceptable nonsurgical treatment option for the management of a chronic orocutaneous fistula in the setting of osteoradionecrosis with exposed bone and hardware in a head and neck cancer patient with a vessel-depleted neck. By fabricating a patient-specific prosthetic appliance, we were able to better control salivary incontinence, promote local wound healing, improve intelligibility and deglutition. In similar cases where surgical options have been exhausted in a hostile orofacial wound environment, the involvement of a maxillofacial prosthodontist can be instrumental in improving the quality of life for the patient.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Not applicable.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors made substantial contributions to the conception, design of the study, analysis and interpretation, composition of the manuscript, and final approval of the manuscript.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT AND SPONSORSHIP

None.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

The author declares that signed Informed Consents were obtained for publication of patient’s images in this manuscript.

ORCID

-

John M. Le, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4836-2487.

-

Kyle Murdock, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7414-3667.

-

Michael T. Kase, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9294-8880.

REFERENCES (19)

-

Girkar F, Thiagarajan S, Malik A, Sawhney S, Deshmukh A, Chaukar D, D'Cruz A. Factors predisposing to the development of orocutaneous fistula following surgery for oral cancer: experience from a tertiary cancer center. Head Neck 2019;41(12):4121–7. Crossref

-

Dawson C, Gadiwalla Y, Martin T, Praveen P, Parmar S. Factors affecting orocutaneous fistula formation following head and neck reconstructive surgery. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2017;55(2):132–5. Crossref

-

Chambers PA, Worrall SF. Closure of large orocutaneous fistulas in end-stage malignant disease. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1994;32(5):314–5. Crossref

-

Bourgeois SL Jr, Alvarez CM. Use of vinyl polysiloxane impression material as an extraoral obturator for orocutaneous fistulas. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2002;60(5):597–9. Crossref

-

Sharon-Buller A, Sela M. An acrylic resin prosthesis for obturation of an orocutaneous fistula. J Prosthet Dent 2007;3(97):179–80. Crossref

-

Conley JJ. Operative complication. In: Complications of head and neck surgery. Conley JJ, editor. 3rd edition. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1979:25–9.

-

Girod DA, McCulloch TM, Tsue TT, Weymuller Jr EA. Risk factors for complications in clean‐contaminated head and neck surgical procedures. Head Neck 1995;17(1):7–13. Crossref

-

Gigliotti J, Ying Y, Redden D, Kase M, Morlandt AB. Fasciocutaneous flaps for refractory intermediate stage osteoradionecrosis of the mandible—is it time for a shift in management? J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2021;79(5):1156–67. Crossref

-

Rice N, Polyzois I, Ekanayake K, Omer O, Stassen LF. The management of osteoradionecrosis of the jaws–a review. Surgeon 2015;13(2):101–9. Crossref

-

Coleman 3rd JJ. Complications in head and neck surgery. Surg Clin North Am 1986;66(1):149–67. Crossref

-

Eskander A, Kang S, Tweel B, Sitapara J, Old M, Ozer E, Agrawal A, Carrau R, Rocco JW, Teknos TN. Predictors of complications in patients receiving head and neck free flap reconstructive procedures. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2018;158(5):839–47. Crossref

-

Clark JR, McCluskey SA, Hall F, Lipa J, Neligan P, Brown D, Irish J, Gullane P, Gilbert R. Predictors of morbidity following free flap reconstruction for cancer of the head and neck. Head Neck 2007;29(12):1090–101. Crossref

-

Haubner F, Ohmann E, Pohl F, Strutz J, Gassner HG. Wound healing after radiation therapy: review of the literature. Radiat Oncol 2012;7(1):1–9. Crossref

-

Sørensen LT. Wound healing and infection in surgery: the clinical impact of smoking and smoking cessation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Surg 2012;147(4):373–83. Crossref

-

Lo SL, Yen YH, Lee PJ, Liu CH, Pu CM. Factors influencing postoperative complications in reconstructive microsurgery for head and neck cancer. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2017;75(4):867–73. Crossref

-

Xu H, Han Z, Ma W, Zhu X, Shi J, Lin D. Perioperative albumin supplementation is associated with decreased risk of complications following microvascular head and neck reconstruction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2021;79(10):2155–61. Crossref

-

Aponte-Wesson R, Knott J, Montgomery P, Chambers MS. Floor of mouth prosthesis with removable depressible tongue: a clinical report. J Prosthet Dent 2022;128(1):107–11. Crossref

-

Kharade P, Dholam K, Bachher G. Appraisal of function after rehabilitation with tongue prosthesis. J Craniofac Surg 2018;29(1):e41–4. Crossref

-

Kumar TP, Azhagarasan NS, Shankar KC, Rajan M. Prosthetic rehabilitation of orofacial donor site fistula following surgical reconstruction: a clinical report. J Prosthodont 2008;17(4):336–9. Crossref