Bone Formation in Peripheral Giant Cell Granuloma: A Case Report with a First Clinical, Radiographic, Ultrasonographic, Macroscopic, and Histopathologic Comparison

Published November 30, 2025

J Diagn Treat Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2025; 9: 100312.

DOI: 10.23999/j.dtomp.2025.11.100312

Under a Creative Commons license (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

HOW TO CITE THIS ARTICLE

Demidov VH, Cherniak OS, Fesenko II, Fil V, Zaritska VI, Chernetsova AP. Bone formation in peripheral giant cell granuloma: A case report with a first clinical, radiographic, ultrasonographic, macroscopic, and histopathologic comparison. J Diagn Treat Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2025 Nov;9(11):100312. https://doi.org/10.23999/j.dtomp.2025.11.100312

INSTITUTIONAL REPOSITORY

https://ir.kmu.edu.ua/handle/123456789/831

SUMMARY

Peripheral giant cell granuloma (PGCG) is one of the benign peripheal reactive lesions of the jaws. Clinically, it is difficult to distinguish from peripheral ossifying fibroma or even metastatic tumor. We report a case of a PGCG in a 64-year-old Caucasian male. Clinically, PGCG presented as a 2.4- × 2-cm saddle-shaped pedunculated lesion of the partially edentulous alveolar ridge of the anterior mandible. The case is unique in that areas of bone formation were noted within the PGCG upon comparison of gray-scale ultrasonography (USG), macroscopic, and histopathological examination. To our knowledge it’s a first ever reported comparison in the medical literature. Indirect ultrasound imaging technique is considered in this article. Prominent intralesional vascularity upon color Doppler USG was proved upon intraoperative step when significant bleeding was noted from soft and bone tissues. Understanding by clinicians of ultrasound patterns in similar cases will facilitate differential diagnosis between alveolar ridge lesions. This paper proves ones again that ultrasound is an essential tool for the oral and maxillofacial surgeons.

KEY WORDS

Peripheral giant cell granuloma, ultrasonography, gray-scale ultrasound, color Doppler ultrasound, bone formation, intralesional vascularity

INTRODUCTION

Peripheral giant cell granuloma (PGCG) is a benign sessile lesion of the gingiva or alveolar ridge mucosa [1, 2]. The old name of the PGCG, fungus flesh (John Tomes, 1848), referred to the fungus-like appearance of the growth [1, 3]. PGCG is a site-specific lesion [1]. The PGCG was previously termed as (1) reparative giant cell granuloma (Henry Jaffe, 1953), (2) peripheral giant cell reparative granuloma, (3) epulis, (4) giant cell epulis, (5) myeloid epulis, (6) osteoclastoma, (7) peripheral giant cell tumor, and (8) giant cell hyperplasia of the oral mucosa [1, 4-7]. Typically, PGCG develops following chronic irritation or trauma [5, 8, 9]. And Kfir et al. (1980) classify PGCG as one of the reactive lesions of the gingiva [10].

Establishing a preliminary diagnosis for alveolar ridge neoplasms and lesions without performing a biopsy is not always a simple task for clinicians. And the use of ultrasonography (USG) is an excellent way to diagnose formations within the alveolar process of the jaws. Unlike other oral lesions and tumors, there is limited literature regarding the imaging characteristics of PGCG on USG [7, 11]. That is why the purpose of this article is to present unique ultrasound data of the bone formation in the PGCG and compare it with macroscopic and histopathological data. In fact, the case highlighted below is an extremely important continuation and addition to the research and publications of such groups of authors as Katsikeris et al. (1988), Dayan et al. (1990), and Ogbureke et al. (2015) [12, 13, 1]. All three studies thoroughly describe the presence of mineralized areas in the thickness of the PGCGs.

CASE REPORT

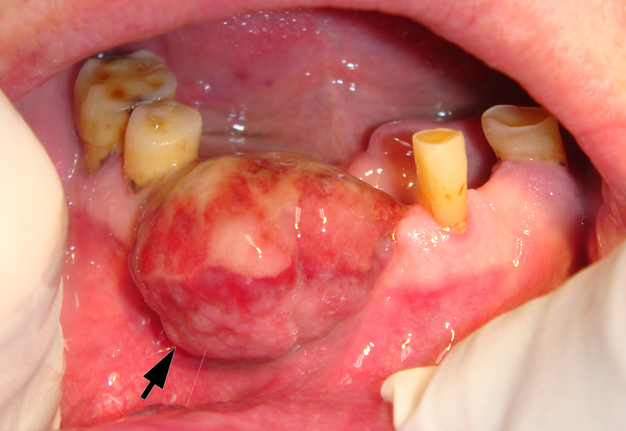

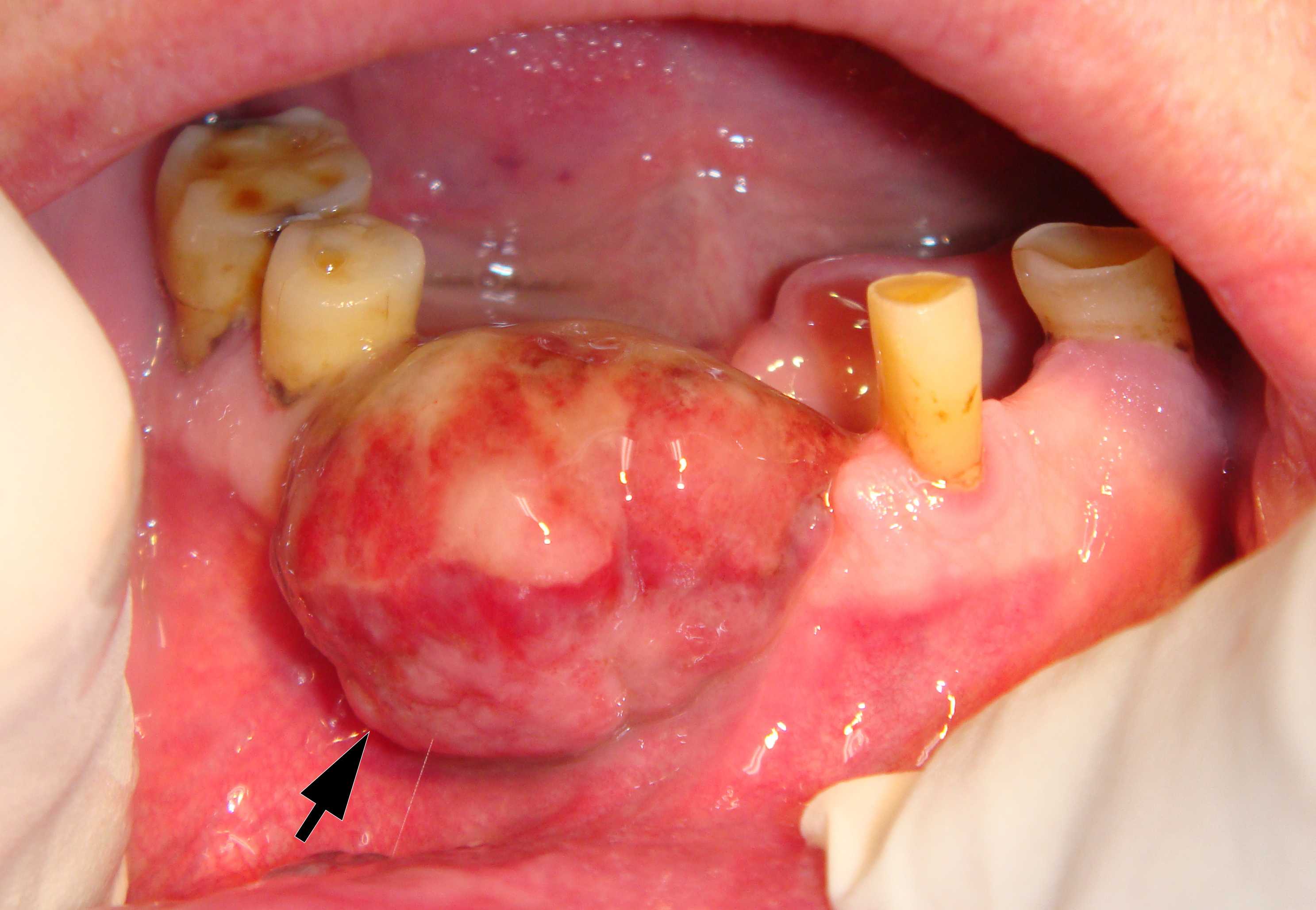

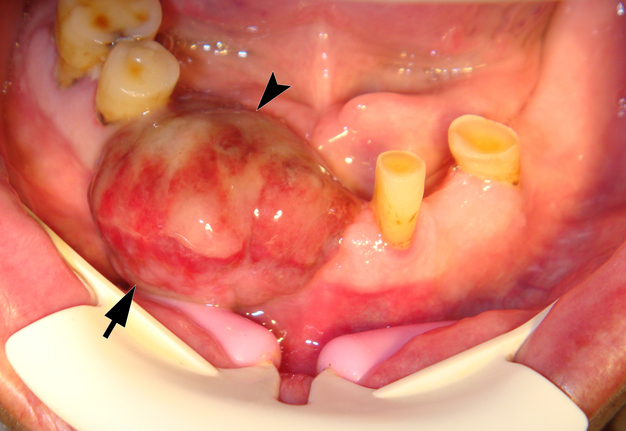

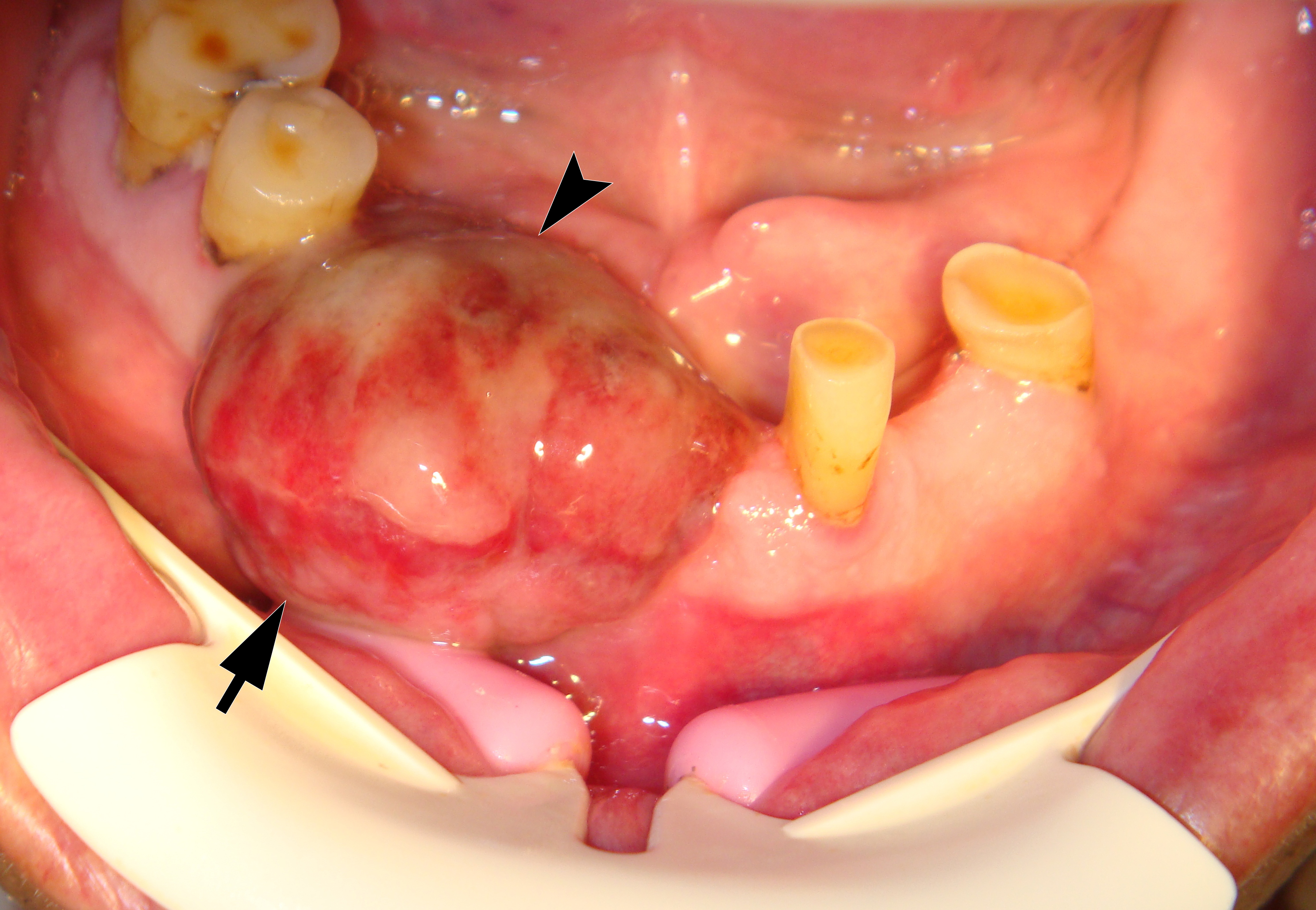

On June 15, 2015, a 64-year-old Caucasian male presented to the Department of Maxillofacial Surgery and Dentistry with complaints of a growth of a neoplasm in the oral cavity for four months. Intraoral examination revealed a saddle-shaped, lobulated lesion with short peduncle (Fig 1) involving the alveolar ridge of the partially edentulous anterior mandible. The lesion was measured 2.4 × 2 cm and consisted of anterior (vestibular) and posterior (lingual) lobe and located between lower right second premolar and left second incisor. The formation had a smooth surface of red, gray, brown, and bluish hue.

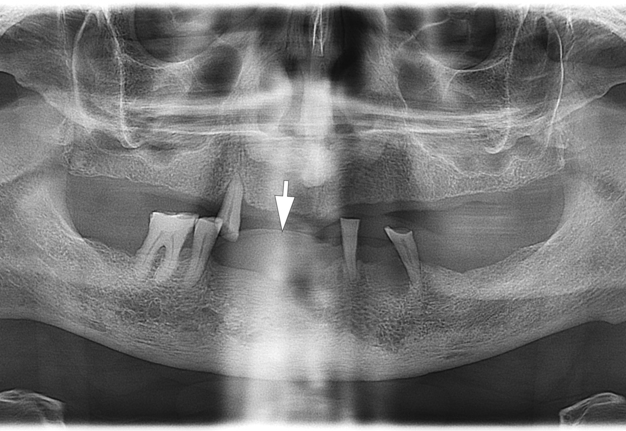

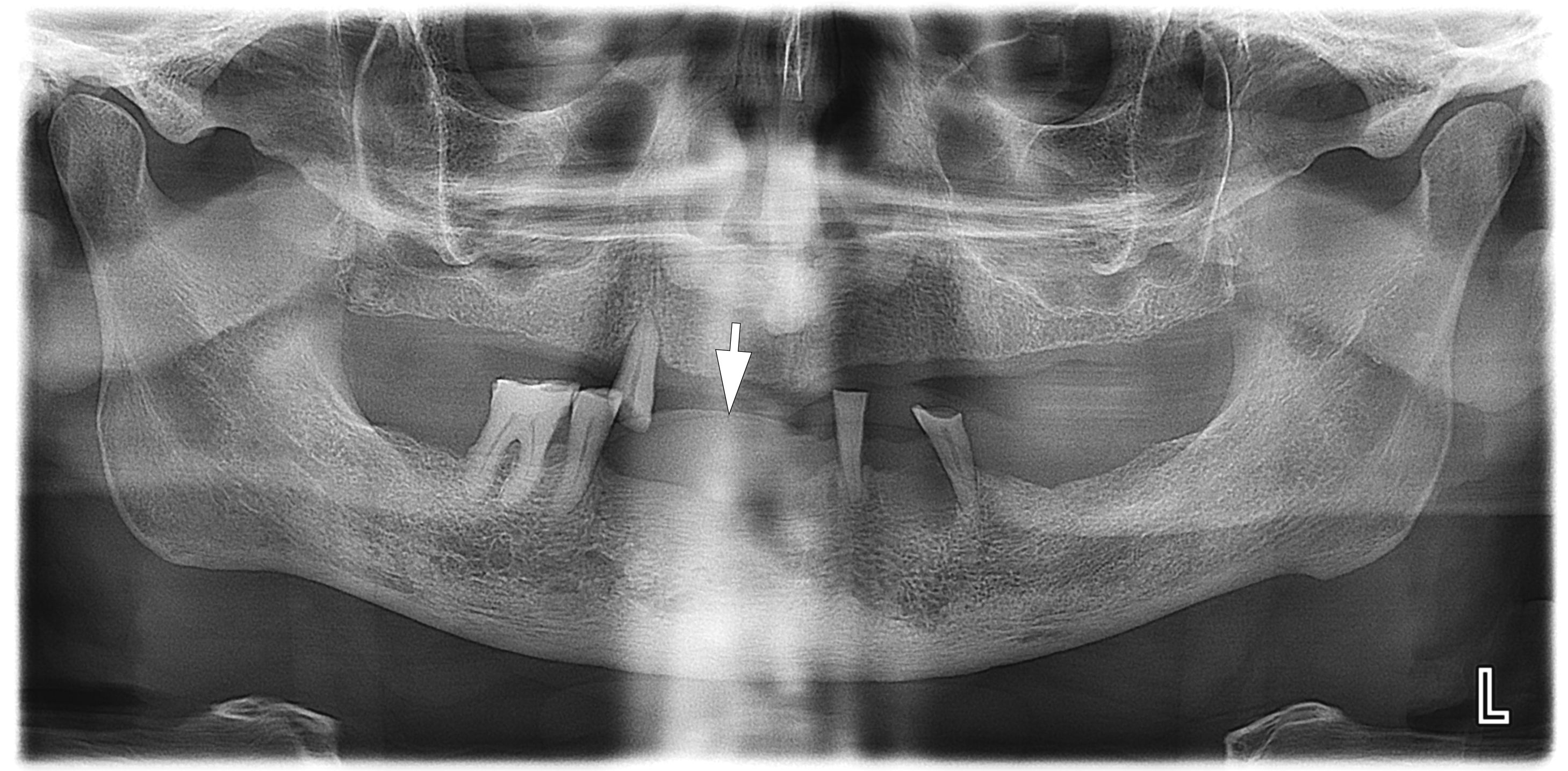

A radiographic examination was performed to assess the condition of the bone tissue and teeth, and an USG was performed to assess the structure and vascularization of the soft tissue lesion. The panoramic radiograph (Fig 2) showed a dome-shaped radiopacity rising above the alveolar ridge of the edentulous area of the anterior mandible.

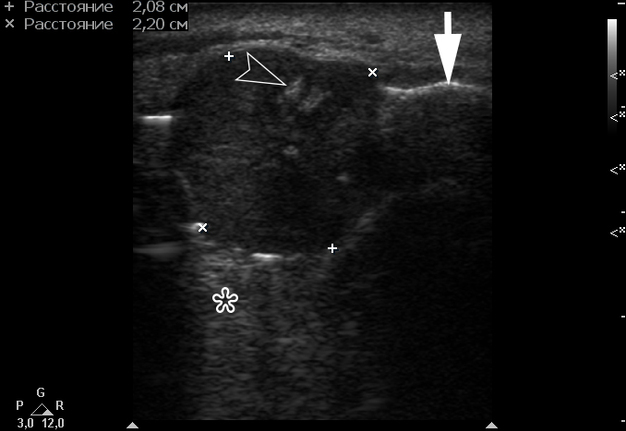

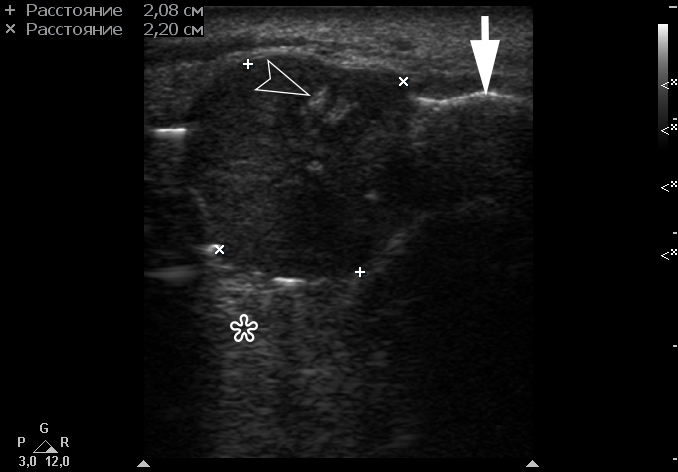

Figure 3 demonstrates indirect ultrasonography of the lesion: The linear transducer (i.e., linear probe) does not come into direct contact with the tumor, but rather with the lip and chin area, thus covering the surrounding tissues.

Gray-scale USG (Fig 4) revealed a unilocular, well-defined lesion with heterogeneous echogenicity. The lesion was measured 2.08 × 2.2 cm and located in a saddle-shaped position on the edentulous area of the anterior part of alveolar ridge of the mandible. The presence of multiple echoic areas and acoustic enhancement behind the neoplasm is noted.

FIGURE 4. Gray-scale ultrasound shows a unilocular, well-defined lesion with heterogeneous echogenicity. The lesion is measured 2.08 × 2.2 cm and indicated by “+” and “×” calipers. The lesion is located in a saddle-shaped position on the edentulous area of the anterior part of alveolar ridge of the mandible. Echoic area of bone formation is indicated by arrowhead. The area of the mandible on which the mass is located is indicated by an arrow and has a hyperechoic appearance. Acoustic enhancement is marked with an asterisk.

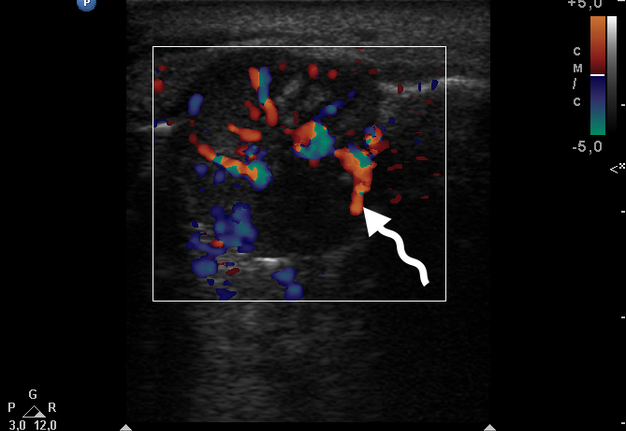

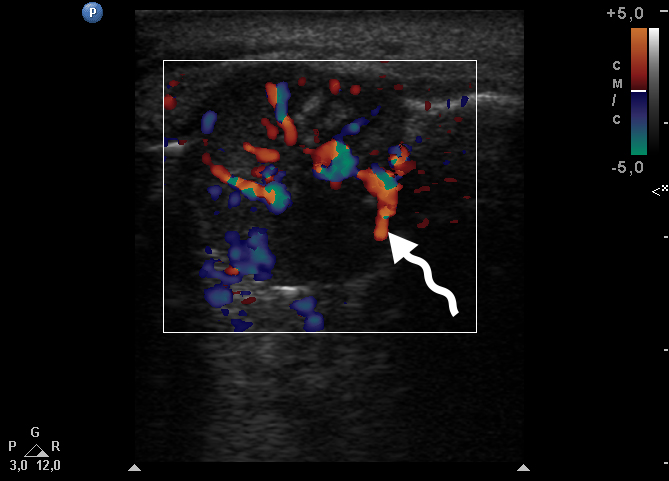

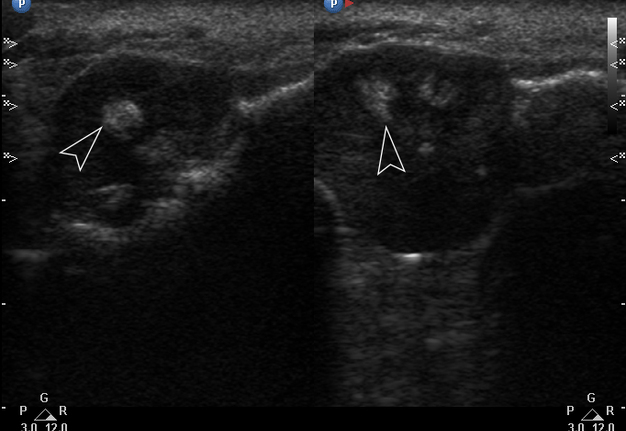

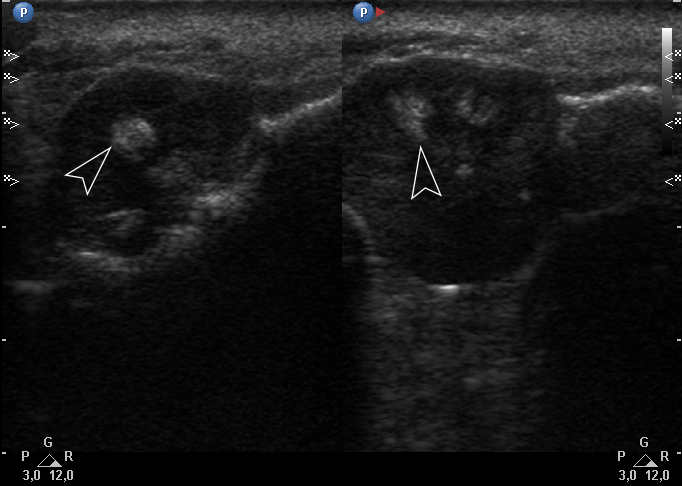

Color Doppler USG (Fig 5) showed prominent intralesional vascularity. Figure 6 demonstrates gray-scale USG of the lesion from two different angles, which allows for better visualization of echogenic areas (i.e., areas of ossification) within the lesion. It was not possible to adequately determine the area of the “stem” of the lesion.

FIGURE 6. Gray-scale sonograms of the lesion from two different angles (A, B). Sonograms show a hypoechoic lesion with multiple echoic areas (i.e., areas of bone formation). It is easy to distinguish areas of ossification (arrowheads) in the thickness of the lesion due to their echoic look. These two images demonstrate that gray-scale ultrasound is highly sensitive for detecting areas of ossification within a neoplasm such as PGCG.

During the complete surgical excision of the lesion (V.H.D.) followed by a peripheral osteotomy, profuse bleeding was noted both from the soft tissues and from the bone tissue of the alveolar ridge. This significant bleeding is confirmation of the color Doppler data on the presence of increased vascularization within the lesion.

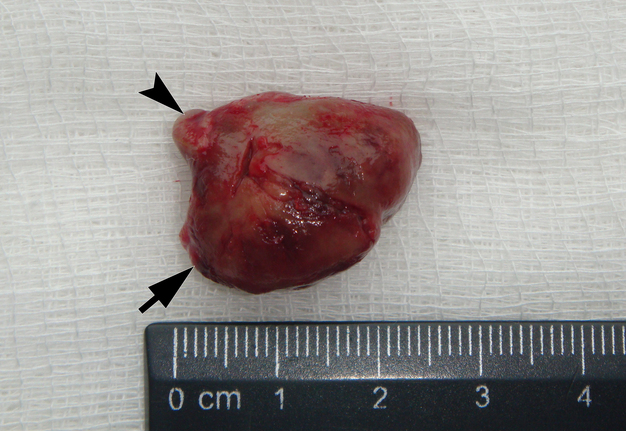

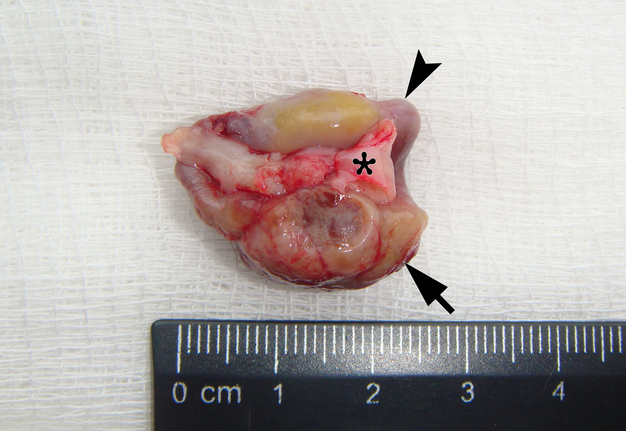

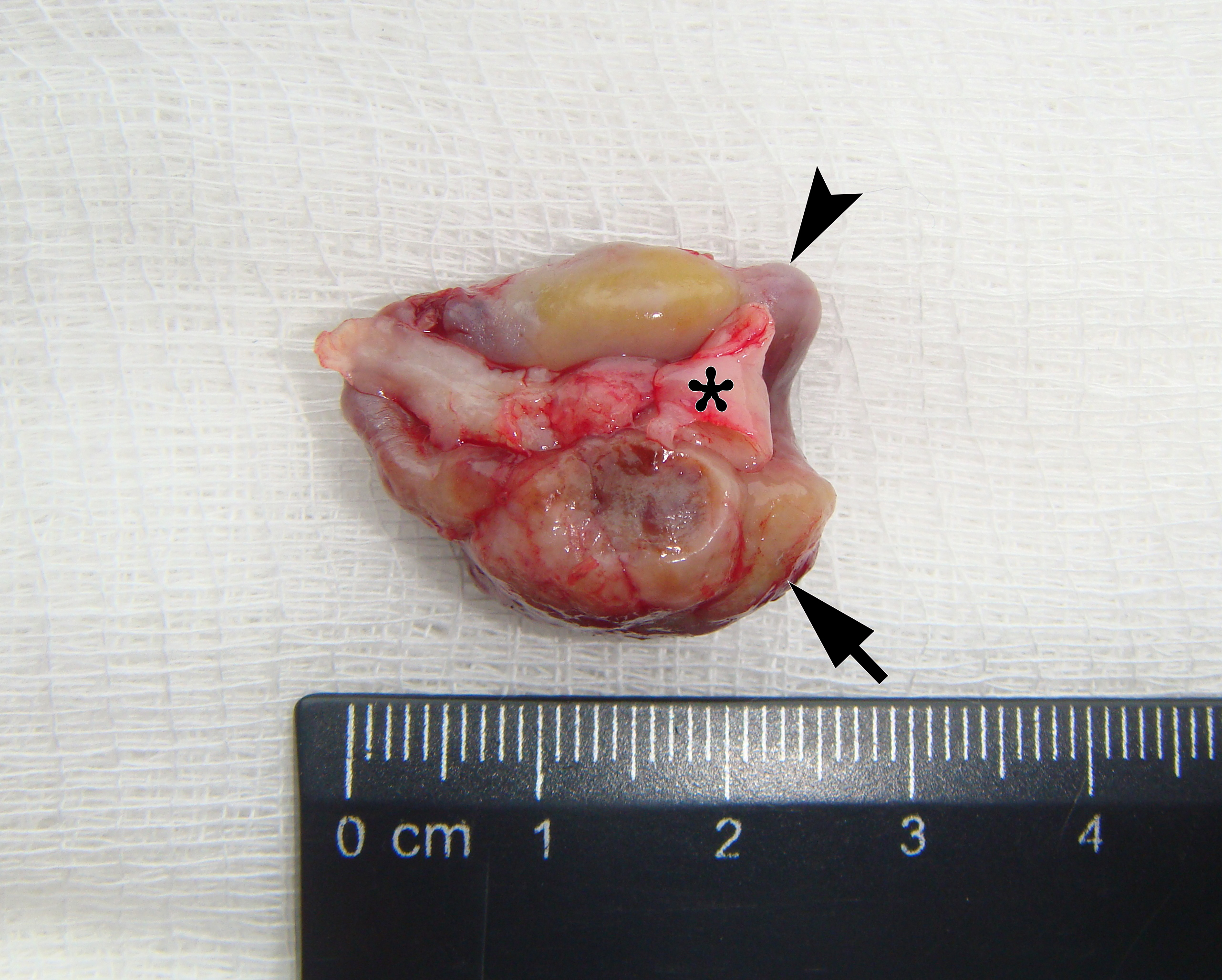

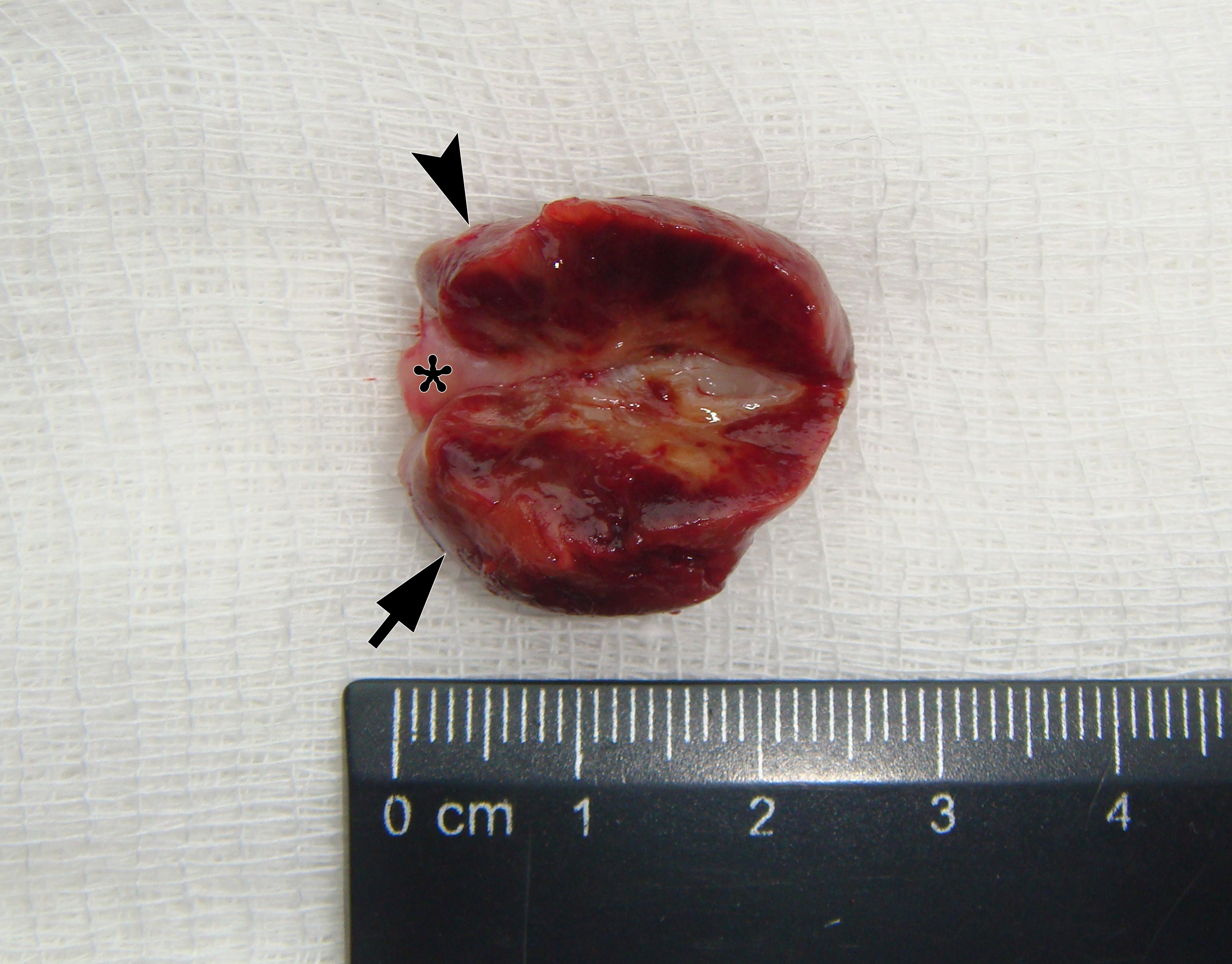

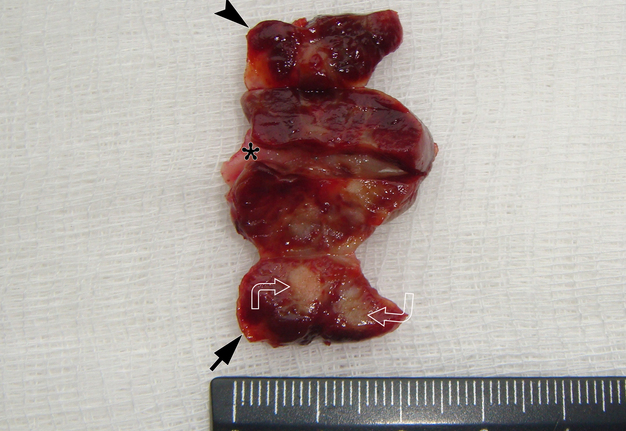

It is worth noting the mushroom-shaped appearance of the lesion, which had an extremely large saddle-shaped “cap” and an extremely thin “stem/stipe.” After removal, when the gross specimen was cut, several areas with calcifications were found (Fig 7). It felt as if the cartilage tissue was being cut when cutting specimen in areas of calcifications.

FIGURE 7A. Macroscopic view of the lesion. Image A shows a top view of the lesion. Image B shows the removed saddle-shaped lesion in inverted position, which clearly demonstrates its shape. Arrow labels anterior (vestibular) lobe and arrowhead labels posterior (lingual) lobe of this lesion. The attachment zone is indicated by an asterisk. The gross specimen after a longitudinal section (C) and subsequent two separate sections (D) of the anterior (arrow) and posterior (arrowhead) lobes of the lesion shows presence of calcified areas (open arrows).

FIGURE 7B. Macroscopic view of the lesion. Image A shows a top view of the lesion. Image B shows the removed saddle-shaped lesion in inverted position, which clearly demonstrates its shape. Arrow labels anterior (vestibular) lobe and arrowhead labels posterior (lingual) lobe of this lesion. The attachment zone is indicated by an asterisk. The gross specimen after a longitudinal section (C) and subsequent two separate sections (D) of the anterior (arrow) and posterior (arrowhead) lobes of the lesion shows presence of calcified areas (open arrows).

FIGURE 7C. Macroscopic view of the lesion. Image A shows a top view of the lesion. Image B shows the removed saddle-shaped lesion in inverted position, which clearly demonstrates its shape. Arrow labels anterior (vestibular) lobe and arrowhead labels posterior (lingual) lobe of this lesion. The attachment zone is indicated by an asterisk. The gross specimen after a longitudinal section (C) and subsequent two separate sections (D) of the anterior (arrow) and posterior (arrowhead) lobes of the lesion shows presence of calcified areas (open arrows).

FIGURE 7D. Macroscopic view of the lesion. Image A shows a top view of the lesion. Image B shows the removed saddle-shaped lesion in inverted position, which clearly demonstrates its shape. Arrow labels anterior (vestibular) lobe and arrowhead labels posterior (lingual) lobe of this lesion. The attachment zone is indicated by an asterisk. The gross specimen after a longitudinal section (C) and subsequent two separate sections (D) of the anterior (arrow) and posterior (arrowhead) lobes of the lesion shows presence of calcified areas (open arrows).

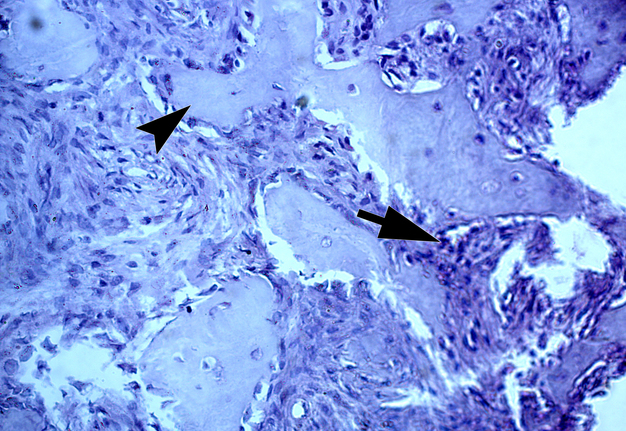

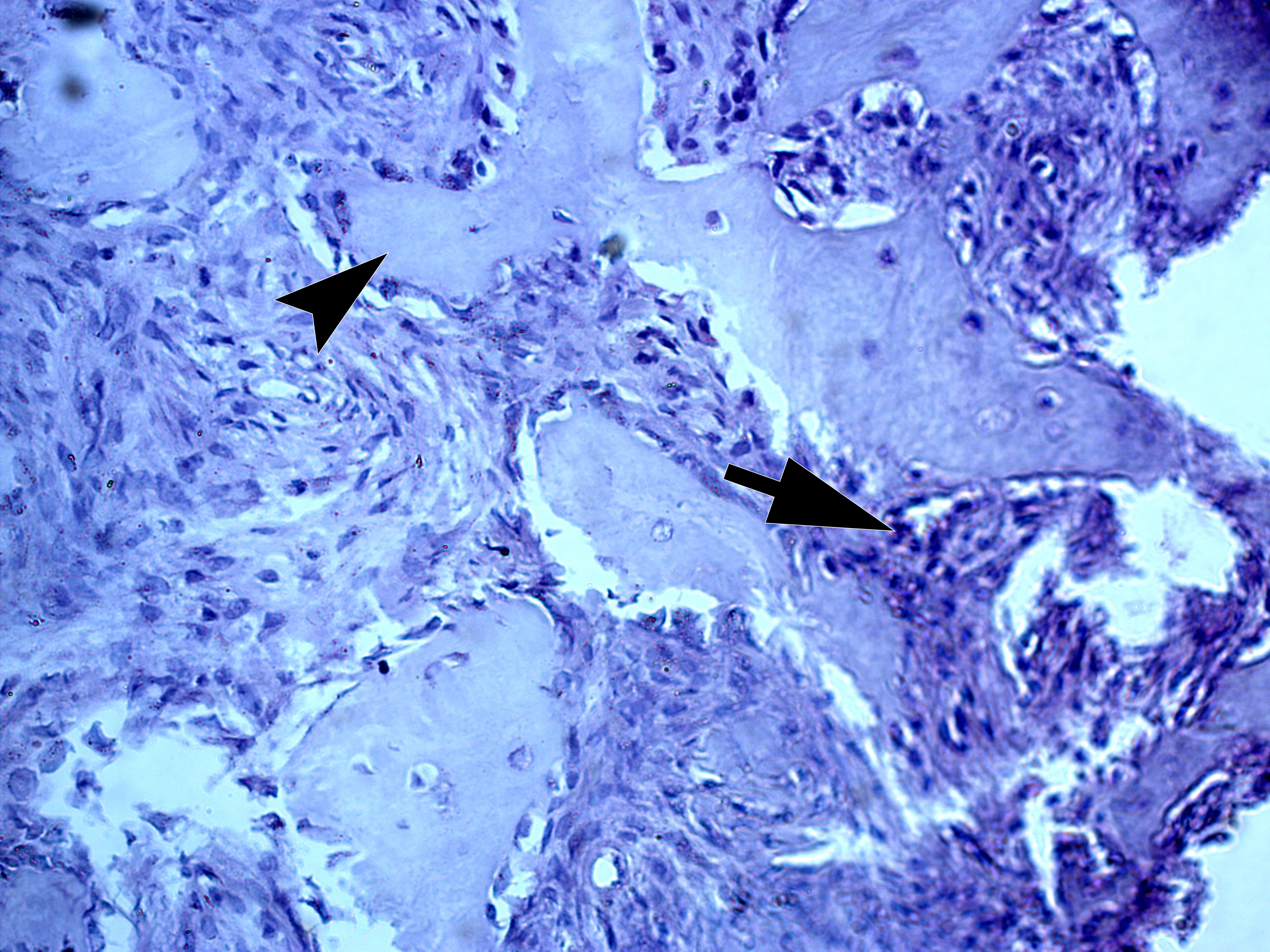

Two highly experienced pathologists (A.P.C. and V.I.Z.) independently established a diagnosis of giant cell epulis (i.e., PGCG). V.I.Z. described the histopathological images as giant cell epulis with fragments of bony beams. Figure 8 shows the histopathological image with bony beams within the cellular mass of a PGCG.

Postoperative period was smooth and a 1-year follow-up showed no evidence of recurrence.

DICSUSSION

The Greek word “epulis” literally means the “(growth) on the gingiva.” In Ukraine, the term giant cell epulis was previously mainly used for PGCG. Interestingly, Boffano et al. (2013) noted that the term “epulis” is a topographic term and does not indicate histopathological differences [14]. Differential diagnosis of PGCG is most often carried out with neoplasms such as pyogenic granuloma [15], peripheral ossifying fibroma [7, 16, 17], hybrid PGCG-peripheral ossifying fibroma [1], inflammatory fibrous hyperplasia [18], ameloblastoma [19], and metastatic tumors [20, 21]. Comparison of the clinical differentiating features in between various entities that resemble PGCG is described in the study by Patil et al. (2014) [20]. The peripheral ossifying fibroma and PGCG are clinically indistinguishable from one another [1].

Katsikeris et al. (1988) and Patil et al. (2014) are emphasizing that PGCG can arise from the connective tissue of the gingiva, periodontal membrane or from the periosteum of the alveolar ridge [12, 20].

Authors certify that local irritating factors such as teeth extraction, poor restorations, food impaction, calculus, ill-fitting dentures, etc. [13, 22].

The simplest method of diagnosing the oral cavity is panoramic radiography. It is also appropriate in the case of PGCG, but it solves a limited range of issues, namely, assessing the condition of neighboring teeth and the presence of bone resorption.

In our case, it was difficult to reliably determine the areas of ossification in the projection of radiopacity (i.e., PGCG) on the orthopantomography. This can most likely be explained by an insufficient level of ossification. In other cases, newly formed bone tissue in the projection of the PGCG was visible radiologically [23].

But on gray-scale sonograms, it was extremely easy for our team to detect areas of ossification within PGCG. Therefore, we believe that ultrasound is a key examination method for reactive jaw formations such as PGCG.

A fairly large number of works are devoted to ultrasound of jaw lesions [24-28]. However, there are not many reliably known descriptions of ultrasound of the PGCG [8, 11].

Orhan and Ünsal (2021) demonstrated five gray-scale and color Doppler sonograms with PGCG [11]. In their case, no pronounced areas of ossification were observed. However, increased vascularization of the lesion was noted. A characteristic location in the anterior region of the mandible was also noted. This coincides with the data of Dayan et al. (1990) [13].

Ewansiha et al. (2022) presented a 12-year-old boy patient and two ultrasound images of the PGCG of the maxilla [8]. Fist one, a gray scale sonogram, and a second one, color Doppler interrogation. Sonograms showed a fairly ovoid‐shaped, heterogenic lesion, measuring 43.5 × 25.6 mm with multifocal echogenic areas due to calcification. On Doppler interrogation, it showed high intraparenchymal flow with low‐resistant spectral pattern.

In our case, we applied transfacial USG (i.e., indirect USG) (Gad et al., 2018) for examination of the lesion and surrounding tissues [28]. The case we presented confirms the data that an advanced vascularization is frequently seen in PGCG upon Doppler examination [11].

In the clinicopathologic study of 224 PGCGs by Katsikeris et al. (1988) was revealed that mature bone or osteoid was found in 44.6% of the PGCG cases, whereas 4.9% of the lesions contained foci of amorphous calcifications [12].

Mineralized tissue was found in 35% of the 62 PGCG cases [13]. Most of the PGCGs which contained mineralized material (73%) were located in the anterior region in both jaws [13]. This fact of such localization is also confirmed in our case.

Important clinical and radiological data were presented in the case series of Kaya et al. (2011) [23]. Panoramic radiography in one of their PGCG cases showed widespread vertically oriented bony spicules at the base of the lesion. This fact confirms our data and literature data [1, 12, 13] on possible histological variants of PGCG with bone formation.

Bouquot et al. (2009) emphasize that osteoblastic new bone formation may be seen in the PGCG [7]. Occasional lesions show an admixture of tissue types compatible with PGCG, peripheral ossifying fibroma, and pyogenic granuloma, presumably because of the common pathoetiology of these lesions. The authors claim that such lesions are traditionally diagnosed according to the dominant tissue type.

An updated analysis of 2824 cases of PGCG reported in the literature showed that excision of the PGCG leaded to reccurence in some cases [2]. Therefore, excision followed by a curettage or peripheral osteotomy should be the first choice of treatment of PGCG [2]. The periosteum must be included in the excision to prevent recurrences (Falaschini et al., 2007) [29].

Thus, our case allows to add two important ultrasound differential features for PGCG located in the anterior edentulous mandible compared to other reactive alveolar ridge pathology. Namely, areas of bone formation and prominent intralesional vascularity.

CONCLUSION

The presented case confirms the histopathological data that most of the peripheral giant cell granulomas which contained mineralized material (73%) were located in the anterior region of the jaws.Moreover, this case shows how ultrasonography can increase the likelihood of establishing the correct diagnosis before biopsy in reactive gingival lesions.

REFERENCES (29)

-

Ogbureke EI, Vigneswaran N, Seals M, et al. A peripheral giant cell granuloma with extensive osseous metaplasia or a hybrid peripheral giant cell granuloma-peripheral ossifying fibroma: A case report. J Med Case Rep. 2015;9:14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1947-9-14

-

Chrcanovic BR, Gomes CC, Gomez RS. Peripheral giant cell granuloma: An updated analysis of 2824 cases reported in the literature. J Oral Pathol Med. 2018;47(5):454-459. https://doi.org/10.1111/jop.12706

-

Tomes J. A course of lectures on dental physiology and surgery (lectures I-XV). Am J Dent Sci. 1846-1848;7:1-68. 121-134, 33-54, 120-147, 313-350.

-

Jaffe HL. Giant-cell reparative granuloma, traumatic bone cyst, and fibrous (fibro-oseous) dysplasia of the jawbones. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1953;6(1):159-175. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-4220(53)90151-0

-

Tymofieiev OO. Tumor-like soft tissue formations of the maxillofacial region and neck. In: Surgical dentistry and maxillofacial surgery. Tymofieiev OO, editor. Volume 3. Lviv: Marchenko TV; 2025:83-110. In Ukrainian.

-

Bernier JL, Cahn LR. The peripheral giant cell reparative granuloma. J Am Dent Assoc. 1954;49(2):141-148. https://doi.org/10.14219/jada.archive.1954.0138

-

Bouquot JE, Muller S, Nikai H. Lesions of the oral cavity. In: Diagnostic surgical pathology of the head and neck. Gnepp DR, editor. 2nd ed. W.B. Saunders, 2009:191-308. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-4160-2589-4.00004-8

-

Ewansiha G, Goshi AA, Ibrahim IM, et al. Massive maxillary peripheral giant cell granuloma in a 12‐year‐old male: Case report. Niger J Basic Clin Sci 2022;19(2):157‐160. https://doi.org/10.4103/njbcs.njbcs_18_21

-

Fligelstone S, Ashworth D. Peripheral giant cell granuloma: a case series and brief review. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2024;106(7):649-651. https://doi.org/10.1308/rcsann.2023.0021

-

Kfir Y, Buchner A, Hansen LS. Reactive lesions of the gingiva. A clinicopathological study of 741 cases. J Periodontol. 1980;51(11):655-661. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.1980.51.11.655

-

Orhan K, Ünsal G. Applications of ultrasonography in maxillofacial/intraoral denign and malignant tumors. In: Ultrasonography in dentomaxillofacial diagnostics. Orhan K, editor. Springer Nature Switzerland AG; 2021:275-317. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-62179-7_18#DOI

-

Katsikeris N, Kakarantza-Angelopoulou E, Angelopoulos AP. Peripheral giant cell granuloma. Clinicopathologic study of 224 new cases and review of 956 reported cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988;17(2):94-99. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0901-5027(88)80158-9

-

Dayan D, Buchner A, Spirer S. Bone formation in peripheral giant cell granuloma. J Periodontol. 1990;61(7):444-446. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.1990.61.7.444

-

Boffano P, Benech R, Roccia F, et al. Review of peripheral giant cell granulomas. J Craniofac Surg. 2013;24(6):2206–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0b013e31829a8316.

-

Saeidi A, Mirah M, Alolayan A, et al. Extensive exophytic gum swelling: A case study. Reports (MDPI). 2025;8(2):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8020052

-

Shrestha A, Keshwar S, Jain N, et al. Clinico-pathological profiling of peripheral ossifying fibroma of the oral cavity. Clin Case Rep. 2021;9(10):e04966. https://doi.org/10.1002/ccr3.4966

-

Alfred Xavier S, Yazhini P K. Peripheral ossifying fibroma: A case report. Cureus. 2024;16(5):e59749. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.59749

-

Babu B, Hallikeri K. Reactive lesions of oral cavity: A retrospective study of 659 cases. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2017;21(4):258-263. https://doi.org/10.4103/jisp.jisp_103_17

-

Orhan K, Koca RB. Ultrasonographic imaging in periodontology. In: Ultrasonography in dentomaxillofacial diagnostics. Orhan K, editor. Springer Nature Switzerland AG; 2021:203-226. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-62179-7_14

-

Patil KP, Kalele KP, Kanakdande VD. Peripheral giant cell granuloma: A comprehensive review of an ambiguous lesion. J Int Clin Dent Res Organ. 2014;6(2):118-25. https://doi.org/10.4103/2231-0754.143501

-

Cherniak OS, Demidov VH, Petrychenko O, Blyzniuk VP. A case report of oral mucosa metastasis of renal clear cell carcinoma mimicking benign neoplasm: Possibilities and limitations of the ultrasonography. J Diagn Treat Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2025;9(7):100307. https://doi.org/10.23999/j.dtomp.2025.7.100307

-

Selmani H, Kubincova M, De Brucker Y. Peripheral giant cell granuloma in a child following tooth extraction. J Belg Soc Radiol. 2025;109(1):8, 1-4. https://doi.org/10.5334/jbsr.3819

-

Kaya GŞ, Yalçın E, Tozoğlu Ü, et al. Huge peripheral giant cell granuloma leading to bone resorption: a report of two cases. Cumhuriyet Dent J. 2011;14(3):219-224.

-

Joshi R, Patel KK, Rathore RK, et al. Evaluation of mandibular lesions via ultrasonography: An original research. Int J Health Sci. 2022;6(S2):14570-14578. https://doi.org/10.53730/ijhs.v6nS2.8819

-

Lauria L, Curi MM, Chammas MC, et al. Ultrasonography evaluation of bone lesions of the jaw. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;82(3):351-357. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1079-2104(96)80365-9

-

Cherniak OS, Zaritska VI, Snisarevskyi PP, et al. Single and multiple odontogenic cutaneous sinus tracts. J Diagn Treat Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2020;4(11):197-216. https://doi.org/10.23999/j.dtomp.2020.11.2

-

Lu L, Yang J, Liu JB, Yu Q, Xu Q. Ultrasonographic evaluation of mandibular ameloblastoma: a preliminary observation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;108(2):e32-e38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.03.046

-

Gad K, Ellabban M, Sciubba J. Utility of transfacial dental ultrasonography in evaluation of cystic jaw lesions. J Ultrasound Med. 2018;37(3):635-644. https://doi.org/10.1002/jum.14374

-

Falaschini S, Ciavarella D, Mazzanti R, et al. Peripheral giant cell granuloma: Immunohistochemical analysis of different markers. Study of three cases. Av Odontoestomatol. 2007;23(4):189-196.